The Gagosian, Britannia Street, London

31 May – 3 August 2019

by VERONICA SIMPSON

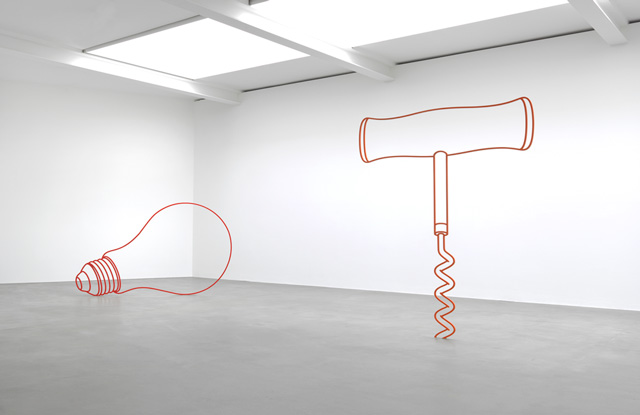

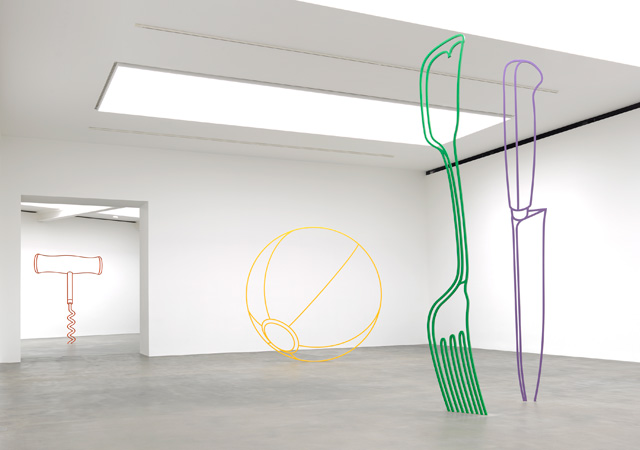

There are benefits to age and experience – a fact we undoubtedly need to be reminded of more often. Michael Craig-Martin (b1941, Dublin), an artist in his late 70s, articulated this point nicely when in conversation with Tim Adams in the Guardian in 2015. He said: “Right now I am doing work that has a certain simplicity and clarity that I could never have done without the previous 50 years.” Having spent the past few decades mastering the beauty and eloquence of the line through an assortment of graphic, pop art-esque celebrations of everyday objects, in two dimensions, Craig-Martin is now delivering that same message in three dimensions. His sculptures deploy his trademark DayGlo colour palate, with a dizzying twist on perspectives. Between three and four metres high, the slim, powder-coated steel frames crisply outline a fork, a ball, a corkscrew, revealing the familiar objects of ourquotidian existence in scales and contexts that both warp and enrich our perceptions.

[image9]

Craig-Martin has been developing these sculptures since 2011, but they didn’t appear in public until 2014, when he showed them in the gardens of Chatsworth House in Derbyshire. There, the sight of a giant, yellow pitchfork, framed against the Tudor and English Baroque architecture of the house and landscaping was a celebratory reminder of all the labour that must have gone into funding, fuelling and even sculpting this palatial environment. For the current Gagosian show, Craig-Martin is placing his sculptures indoors for the first time, in a setting that couldn’t be less ornamental. The white walls and concrete floors of the gallery give us these “line drawings in the air” completely free of context (aside from the underlying seal of art-world approval).

[image6]

At the opening, Craig-Martin is happy to chat, and clearly delighted with the way these works become charged in a whole different way by this setting. He tells me: “When they’re outdoors, one of the things that’s interesting about them is, because they’re transparent, you read the landscape right through them. Here, because there is no landscape, you see them much more for what they are. And it’s much clearer that what I’m doing is drawing in space. They are sculptures of drawings, not sculptures of objects. You really have the sense of them being drawings.”

[image2]

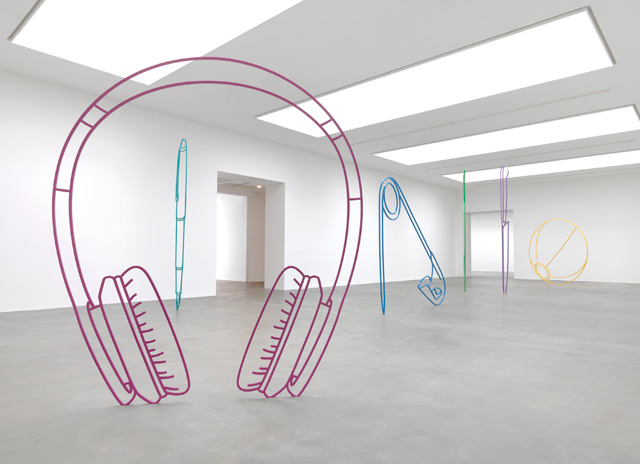

There is an Alice in Wonderland quality to coming up close and personal with these “drawings”, which stems from that sense of being in two different dimensions at once (the two-dimensional and three-dimensional), as well as from being able to roam around and between the four-metre-high, paired Fork and Knife (green and purple) (2019), or waltz up to a giant pair of Headphones (magenta) (2019). The inverted scale between the viewer and the sculptures, between the sculptures and the space, not to mention the eye-popping, clearly synthetic colours, all combine to psychedelic effect.

[image11]

Then there is the shift in perception as you go close – the “pucker” lines of the headphones, which communicate that softness so clearly from afar, transform the earphone elements into something more like eyes, thickly lashed, when you come close to the work; it seems that if our minds cannot take in the scale of the whole work, we must break what we see down to “read” it differently, up close.

[image4]

The show is across two rooms, with the smaller, far room featuring a zesty, curvy conversation between Corkscrew (orange) (2019) and Bulb (red) (2011) – the earliest work in the show. But the Corkscrew is also placed dead centre in the doorway between the two galleries. And, seen from afar, Corkscrew becomes energised in a completely different way: the “screw” element appears to erupt from the ground into a joyous, outstretched hooray, enacted by the handle.

Perhaps the most transformed object at scale, however, is the Safety Pin (blue) (2019). When this humble item - a tiny but crucial symbol of both comfort and hygiene, symbolising domesticity, the care of infants, of clothes and fabric - is seen stretched over a span of several metres, it’s the beauty and simplicity of its engineering that is writ large.

[image3]

Engineering was also required to insert these sculptures into the gallery. Craig-Martin tells me he was worried it wouldn’t be possible: outdoors, each sculpture comes with its own stabilising cage that is dug deep into the ground. However, between the artist, the gallery and the fabricators, they found a way, by adding a “tab” to the base of the sculpture, which slots into the concrete. Whatever repairs to the floor the gallery had to undertake afterwards have been seamlessly done; which adds to the disconcerting, implausible quality of the fork and knife, as their upended top parts appear to melt into the ground.

Over the course of his career, Craig-Martin has drawn hundreds of everyday objects, so will these new works be joined by many more? Seemingly not. He says: “Very few of them can be turned into sculptures, because they won’t stand up. They’re too top heavy, too complicated. They don’t touch the ground in the right way … Out of 500 drawings, I’ve found 15-20 (that work). It’s very difficult to find an image I can do it with.”

[image5]

If there is any quibble about the ones he has assembled here, it is with the Fountain Pen (2019). I’m not sure why it doesn’t stack up for me – the lines are elegant enough, the form graceful. But perhaps it is the fact that it always was, and still is, a luxury item – a refined writing tool that, these days, you might regard as pretentious if you saw it in use. It lacks that quotidian quality that makes the inflation and celebration of the other forms so delightful. And if the point is to highlight it as obsolete – in the manner of Craig-Martin’s excellent Transience series (celebrating obsolete technology) for the Serpentine in 2015 – then the fact that it isn’t, that people still use them and will probably go on using them while the fancy takes them, dilutes or even demolishes the intended gag. But that is a minor quibble. Mostly, these new sculptures – especially in this setting - prod, provoke and delight in equal parts.