New Museum, New York

30 June – 3 October 2021

by ELIZABETH BUHE

The New Museum’s summer shows on Ed Atkins and Lynn Hershman Leeson investigate personhood in the face of technology, and the questions they ask of us are nothing short of profound. How does technology change the body? How is a body constructed, socially and biologically? What is personhood, and to what objects or beings is this dignity granted? Both artists route their investigations through their own bodies, but their stakes are otherwise quite distinct. Atkins is interested in theorising reality and illusion, locating the contours at which these concepts collapse, and exploring the losslessness of memory and image. Hershman Leeson probes not only the mechanics, but also the ethics of identity, rooted in a decades-long engagement with feminist discourses of performance, the cyborg and corporeality, as well as more recent conversations about environmental justice and biotechnology.

[image14]

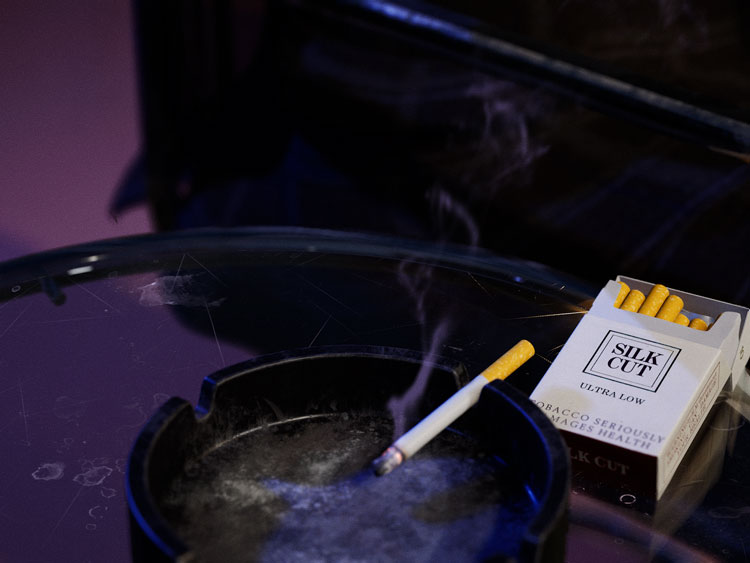

On the fourth floor, Ed Atkins: Get Life/Love’s Work centres on The Worm, a video projection of a computer-generated Atkins mid-conversation with his mother, who remains off screen. In a checked suit and seated in chrome chair, a hyper-real Atkins fumbles, his hand failing to grasp his cigarettes. His pores are too big, his teeth too perfect. In a wistful and tentative voice, his mother confesses anxieties around being unlovable or undesirable.

[image12]

Wall-mounted texts penned in collaboration with an anonymous author project, Contemporary Art Writing Daily, point up the failings of technology (eg, 19th-century milk rendered toxic via added preservatives), realism’s shift in domain from art history to the corporate world, or (via a semiotic chart) the impossibility that representation can connote reality. All of this is shot through with autobiography and genealogy, sometimes coded as likeness: Atkins’ avatar is based on a digital skeleton rendered from a head brace and camera the artist wore, while one of three machine-embroidered acoustic panels resembling quilted tablecloths draw from his father’s diary. The work reflexively acknowledges the links that that digital and human reproduction share – iteration, the regulation of the body, and the imperfect transfer of mimetic information.

[image2]

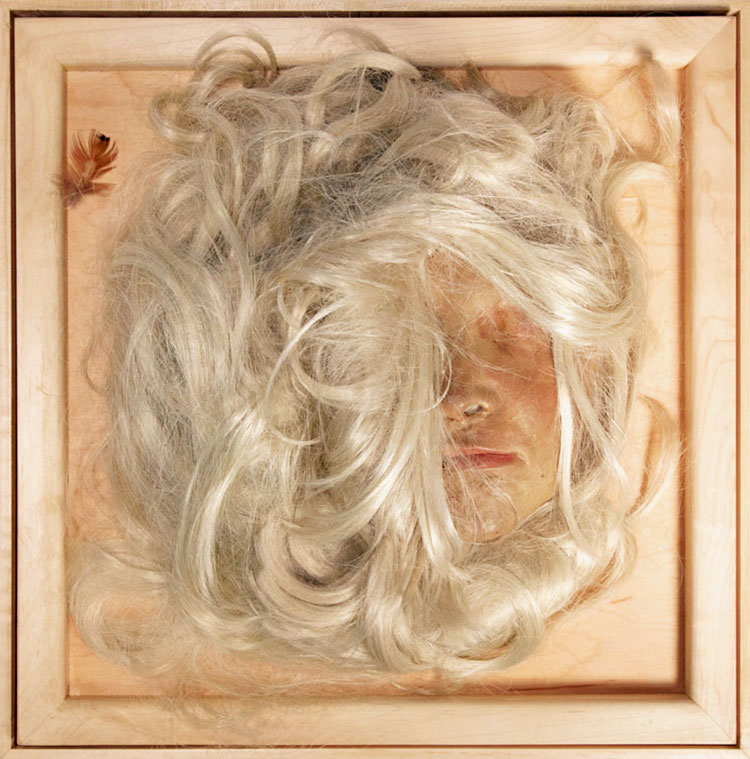

The maternal is an unexpected link between Atkins’ work and Lynn Hershman Leeson: Twisted. The latter, a teeming, stunning retrospective, spans the artist’s 60-year career and opens with drawings pertaining to the elastic pregnant body. It is fascinating to trace this thread of the artist’s engagement with her own corporeality and with reproductive technologies through her oeuvre, right up to Room #8, a 2018 project that records her artistic archive in DNA, the vials for which are on view, secured in a mirrored box behind a thick lab door. In Pregnant Woman in X-Ray Suit (1977), for instance, a figure rendered in a sinuous ink line bends backwards, nude except for ballet shoes. An annotation near her abdomen, “special sound adaptors for foetos [sic] – special sound ‘echo’ for duet with mother”, evinces an interrogation of the limits of self and other at a privileged moment when those limits are especially hard to discern. Drawings, digital prints and reliefs in the first gallery, hung salon-style cheek by jowl, show Hershman Leeson working out the systems of the body: delicately rendered beings have gears for hips (X-Ray Woman, 1966) and heart (Robotic Horse Interior, 1971), while another cyborg is framed by graph paper (Dress Ray, 1966), its swirling insides outstripping analogue systems of measurement. Dozens of drawings, many never before exhibited, show Hershman Leeson’s consummate skill as a draughtsperson, recasting the subject matter of Ingres, Leonardo and Daumier as a world experienced through the female body. Crisply delineated forms and solid fields of colour recall the near-pop aesthetic of Emma Amos or Kiki Kogelnik, but death is here, too, in an untitled wax mask set in plaster (1974) and the Breathing Machine sound sculptures of 1966-68. When activated by motion sensors, these emit recordings of the artist’s breath or ask questions of the viewer, in a brilliant answer to contemporaneous debates about the beholder’s presence relative to sculpture. The artist, diagnosed with cardiomyopathy during her pregnancy in 1965-66, was acutely aware of her mortality in this decade.

[image3]

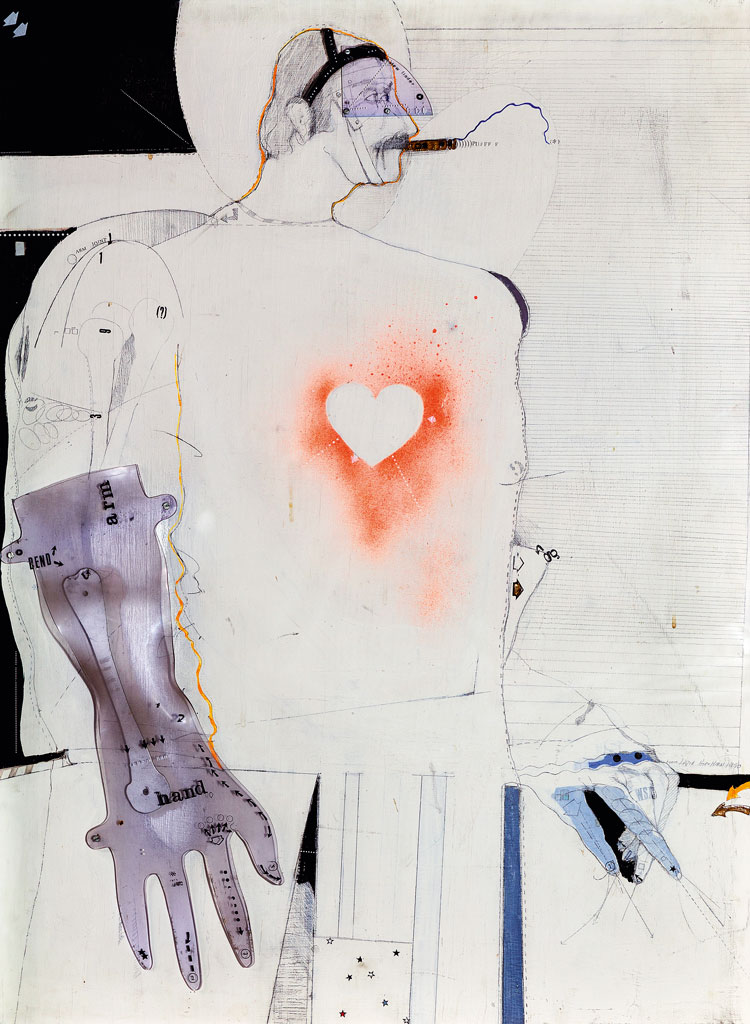

Concern with embodiment gives way to the performance of the postmodern self by the mid-70s. Hotel Commercial (1974), in which multiple people claim to be the artist, makes this point explicitly, while the silver gelatin prints of the Phantom Limbs series (1985-88), which merge images of the female body with tools of technological reproduction, share with pictures generation artists such as Robert Longo or Cindy Sherman a critical attitude toward commercial media’s mechanisms of seduction and desire. Unlike Sherman, who in her Untitled Film Stills (1977-80) hid the camera, Hershman Leeson’s flagrantly bionic beings – one has electric plugs for legs – are more akin to the collaged robots of Berlin dada insofar as they image a potentially dystopic future in which control over technology is the sole domain of the powerful (witness the recent rise of commercial astronauts) or in which our bodies are infiltrated by machines.

[image5]

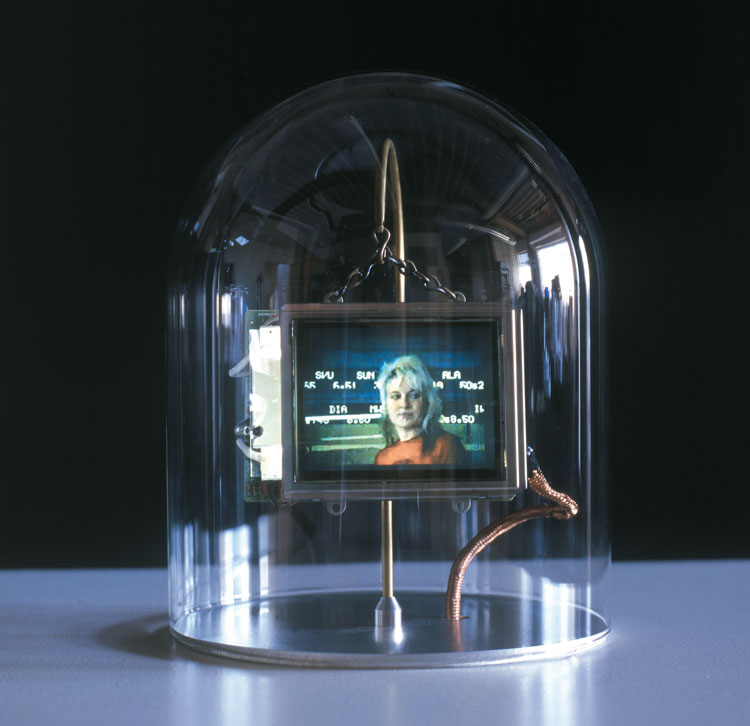

Across the gallery, Tillie, the Telerobotic Doll (1995) and CybeRoberta (1996) surveil us with their camera-eyes, transmitting our own likenesses via live-stream on a small monitor. Though now cast in somewhat different terms, the conceptual investments of Hershman Leeson’s Dollie Clones continue to motivate our critical discourse, making this work seem unexpectedly contemporary. I am thinking, for example, of intellectual debates about the ethics of surveillance in the digital realm, who is entitled to look, the right to opacity and non-disclosure, or the affective capacities of non-human things.

[image11]

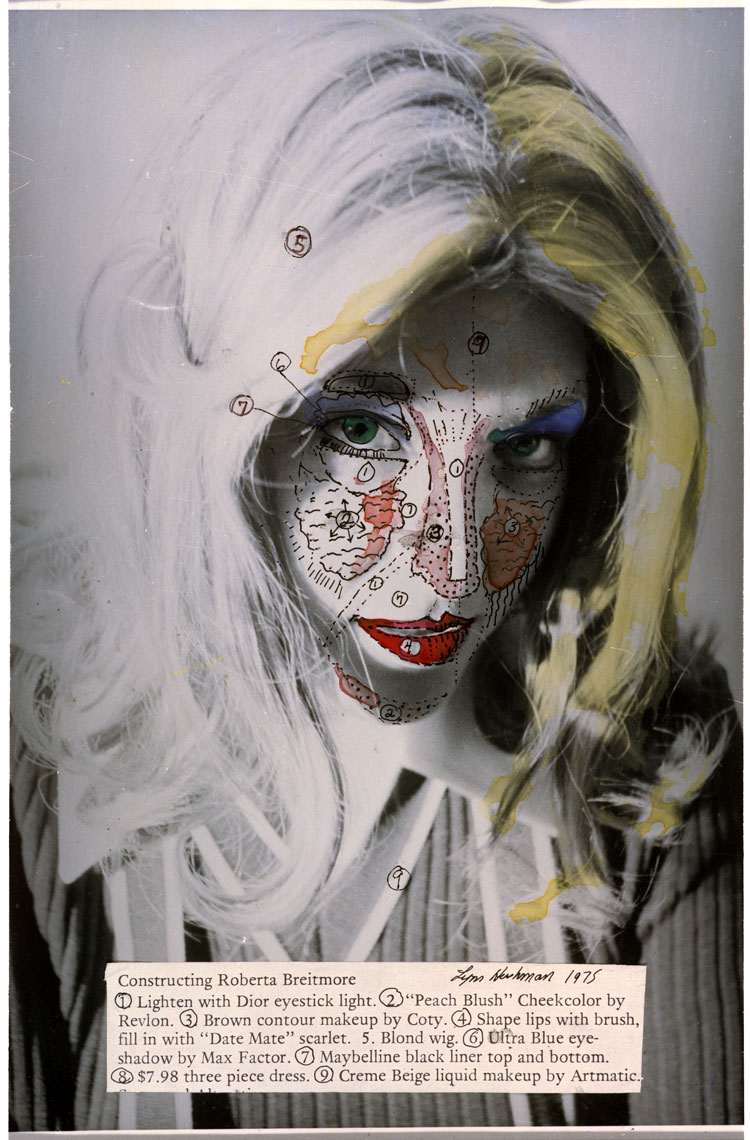

Both Atkins and Hershman Leeson explore the extent to which identity is constituted by the accumulation of artefacts from one’s life and what evidence we take as “authentic” markers of that self. While, in The Worm, Atkins plumbed his own life for source material, the pill bottles, sunglasses, cheque book and diary pages on view in Hershman Leeson’s show are not hers but those of an entirely different persona, the fabricated identity Roberta Breitmore, from the eponymous, years-long performance piece (1972-79). Again, the two artists pursue different ends: Atkins focuses on rendering identity through likeness and the surface of the skin, whereas Hershman Leeson addresses the practical but also deeply philosophical question of how transmutable things (identities, natural resources) give rise to life. This is especially evident in the most recent works on view which, following the show’s gap in work from the 2000s and 2010s, demonstrate what the artist has called a shift from digital presence to a biological way of thinking. These extremely ambitious projects are primarily collaborations with scientists: Twisted Gravity purifies contaminated drinking water, while Infinity Engine (2014-ongoing) explores data storage via DNA and the effects of genetic engineering.

[image8]

It seems nearly impossible to make sense of these shows outside the intimate entwinement between ourselves and technology forced ever more by the pandemic. This would seem to pertain for Atkins, too, who attends to this shared circumstance at length in a meandering “Erratum Letter” in the catalogue. In it, Atkins notes that the limitations of working during Covid, as well as a rapidly morphing understanding of “isolation” (he had originally intended to interview “some gorgeous, isolated strangers” rather than his mother), drastically narrowed the parameters of the work. Such an acknowledgement forces a reckoning about the extent to which the shared condition of quarantine and loss – the closest to a universal experience those of us who did not live through a world war are apt to endure – might be said to circumscribe the work (or any artwork) rather than simply offering a lens for its later interpretation. Many artists made flowers or family members their subjects during those long months, in a pragmatic reduction of process and materials.

[image17]

So, I wonder: how long does this subtext remain salient, more so than is any other limiting condition in the process of making? When does the performance of vulnerability shade into misogyny, especially when its exposes the vulnerabilities of those closest to us? Both shows proceed from an acknowledgement of autobiography. But the considered feminism of Hershman Leeson’s oeuvre, and especially the expansive scope and reparative ambitions of her newest work, makes Atkins’ seem all the more troubling. The hardships of the past year would seem to require more care towards others, whether fleshy or digital, near or far. Taken together, the New Museum’s shows make a strong case for this ethical commitment.