Perrotin Paris

11 January – 21 March 2020

by JOE LLOYD

Spare a thought for the Venus de Milo. As if losing her arms were not enough, she has acquired of late a sickly, powder-blue pallor. The joints from which her arms once sprung have rotted away and the flesh beneath has metamorphosed into painful-looking shards of blue calcite crystal. More crystals seep out from her left leg. Worst of all, there is a fist-sized puncture in her head.

[image2]

Conservators need not fear. This is not the Venus herself, but a cast by the New York-based artist and designer Daniel Arsham (b1980). She is in good company. Arsham has filled the halls of Perrotin, Paris, with a pantheon of her antique compatriots, all of whom are suffering from a similar process of decay. Take Lucilla, daughter of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius. Her disembodied head is wracked by jagged shards of pyrite. Nearby, a dryad has turned pink, a chunk of her face caved in to reveal a seam of rose quartz. And sharing a fate with these pagan figures, the horned Moses – as imagined by Michelangelo for Julius II’s tomb in Rome – seems to be falling apart before our eyes, his torso mouldering away.

[image10]

These works feature in Paris, 3020, an exhibition that looks back to the art of the distant past and imagines how it might appear in the distant future. It is an extension of Arsham’s recurrent practice of ageing up emblematic objects and technologies of the past half-century into colourless, corroding husks. The nine-item Future Relics series (2013-18), for instance, applied this process to a Casiotone keyboard, a Sony Walkman and a Polaroid camera. Arsham embarked on his project after visiting Easter Island, where he witnessed the discovery by an archaeological expedition of the discarded tools of their long-gone predecessors. This prompted an interest in archaeology’s ability to dissolve time, “to collapse the past and the present”.

[image7]

It is telling that Arsham began this process with design objects. He is one among a generation of practitioners operating within the traditionally separate disciplines of art and design. He was educated in the latter at the Cooper Union in New York, and his career to date resembles not a straight road, but a roundabout sprouting off in multiple directions. His early projects include set design for the seminal dance choreographer Merce Cunningham – a role previously occupied by postwar giants such as Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg – and fitting rooms for Dior (both 2005). Out of the latter came Snarkitecture, his collaborative practice with the architect Alex Mustonen: the two have since created a series of architectural installations, often for fashion labels.

Arsham was born partially colour blind and, until recently, one of the connective threads in his output was the use of white monochrome. Then, in 2016, he acquired vision-correcting lenses. Colours began to seep into his work, albeit sparingly, as if by one who understands their preciousness. In Paris, 3020, Arsham’s classical casts are tinted blue, pink and black with natural pigments. Although the former two are pale, they register as an extreme contrast with the austere white by which we are used to perceiving classical sculpture. This colouring might offer some reference to the vibrant, perhaps even garish paint now known to have decorated ancient artwork, though it seems to emanate from some corruption within, bubbling outwards until it causes fractures in the surface.

[image4]

The crystals often intensify this colour, as if the sculptures’ flesh has been scabbed up; they also reference a potential deterioration of marble, which is itself largely composed of the crystalline calcite. In the right condition, marble sculpture might indeed deteriorate in a not entirely dissimilar way. Though improbable, even fanciful, the works in Paris, 3020 do have some grounding in the realm of possibility. In this, Arsham’s work opens a material dialogue with the classical art whose form it assumes.

It also opens up a cultural historical one. Classical sculpture has an extraordinary story of revival and reproduction. The relics of a handful of long-lost civilisations have to come to define western ideas of the human form and beauty since the Renaissance, to a degree that no other artistic tradition can rival. The 19th century had a particular mania for replicating and disseminating ancient marvels. The artworks that comprise Paris, 3020 were cast at the moulding atelier of the Réunion des Musées Nationaux — Grand Palais in Saint-Denis, the present incarnation of an institution established in 1794. Founded to supply the Louvre with casts, it now houses more than 6,000 sculpture moulds, from which it provides casts to other museums and private clients. By working with the atelier, Arsham continues the long history of reproducing fragments of classical art in the state in which they were rediscovered by moderns: another dissolution of time and collapsing of history.

[image5]

There is no shortage of contemporary artworks drawing on the form of classical and classically inspired sculpture, as periodic survey exhibitions (for instance, The Classical Now at King’s College London in 2018) have demonstrated. Some, such as Guan Xiao’s film David (2013), comment on their “iconic” status. Others, such as Léo Caillard’s series of photographs Hipsters in Stone (2013-2018), in which famed sculptures are seen wearing contemporary apparel, use this status for little more than an Instagram-friendly joke. The most bombastic burlesque of classical sculpture to date is almost certainly Damien Hirst’s Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable (2017) in Venice, where the former YBA staged the rediscovery of an unspeakable hoard of ancient treasures for the benefit of his collectors.

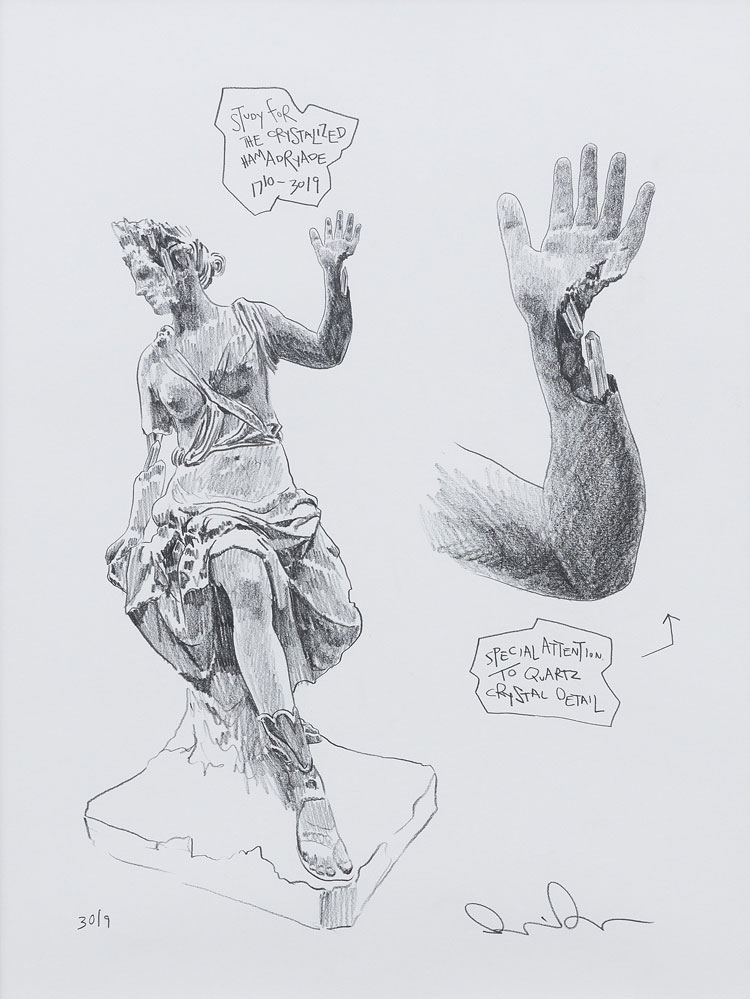

Arsham is substantially more engaged with the material qualities and cultural history of these sculptures themselves than any of these artists. And with Hirst’s wreck still loitering in the memory, it is pleasant to see an artist interested in classical sculptures for their own reality, rather than their prestige as icons and obvious saleability. Arsham’s presentation at Perrotin does contain some traces of his work with luxury retailers — the glow-from-below platforms that the larger sculptures stand on, the deft sketches that explain the history and materials involved in various works. But what is more apparent is his respect for his source material, even as he subjects them to grievous rot.