Serpentine North Gallery and assorted venues, London

22 June – 18 September 2022

by VERONICA SIMPSON

It was a glorious English summer’s evening. The doors and gates of the Serpentine North Gallery, set within the rolling acres of Hyde Park in London, were flung wide. A hotchpotch of visitors, of all ages, classes, genders and nationalities, were standing on patches of fading grass, clutching the last of the fast-diminishing private view free drinks. Few of them were wearing masks. It is funny how quickly the shifts in the cultural and Covid ecology manifest themselves – concern about the latter diminishing as the appetite for the former reasserts itself. London seemed to be back in full sociable swing.

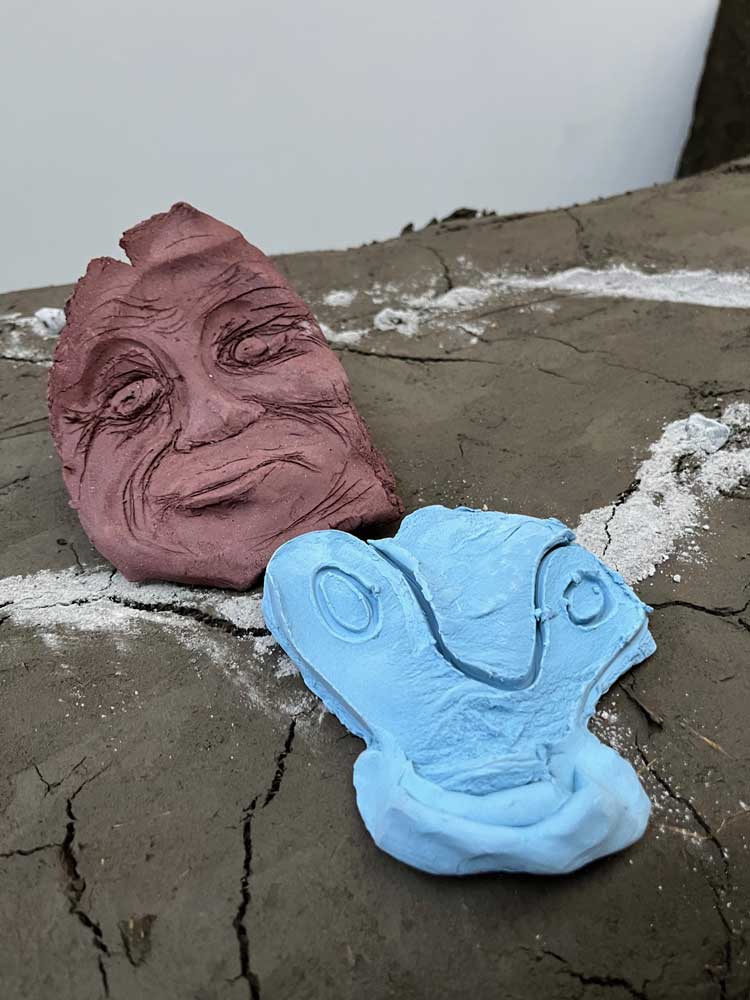

As I entered the familiar gallery, attached to Zaha Hadid’s voluptuous spaceship, AKA The Magazine Café, the scent of damp earth was the first thing to assault my nostrils. It turned out to be emanating from a bank of still wet, newly formed clay in the form of a wall that had been built around the back of the gallery by the South African artist Dineo Seshee Bopape and the Brazilian-born, self-styled “animist and sound artist” Katy’taya Catitu Tayassu. Its upper surface was sprinkled with small, picturesque clay heads, a carnival cavalcade of facial expressions.

[image2]

Or maybe the smell was coming from Sissel Tolaas’s “unique smell score”, which was designed to draw on “the emotional power of smell” – though my initial impression was of drains and damp; not such good emotional associations there. But given that this work was in no way visible to me at the time, it would be hard to tell.

Moving in towards the middle of the three internal gallery spaces of this former coach house, there was a far more pleasurable, herbal fragrance of not-quite-dried flowers and grasses. These had been stitched across a webbing structure created by the artist Tabita Rezaire (who also lists herself as a doula and a cacao farmer) and the architect Yussef Agbo-Ola of Amakaba and Olaniyi Studio.

[image3]

The work, called Ikum: Drying Temple (2022), is dedicated to medicinal plants “to explore our relationship to them and their healing powers”. In the arched gallery beyond it, the musician Brian Eno has created a flickering cave of artificial candlelight and inserted a tranquil soundscape, which could have induced a state of meditative calm if it weren’t for those visitors who insisted on talking away to their chums – I blame the free drinks. In some ways, the whole experience was more like being at a festival than in an art gallery, but then this is a show whose proto-hippy credentials are broadcast in its title: Back to Earth.

It has been a long time landing. First conceived by the Serpentine’s former curator of general ecology (and now ecological consultant), Lucia Pietroiusti (see her interview with Studio International), its gestation began in 2018 as part of plans for a celebration of the Serpentine’s 50th birthday, in 2020. To that end, Pietroiusti with a large curatorial team had invited a huge range of artists to propose campaigns or ideas in response to the question: how can art respond to the climate emergency? While imagining the response would be comprised largely of consciousness-raising posters, the team was so inspired by the deluge of responses it received, including many proposals for actions and interventions, that multiple commissions were set in motion, some of which have been popping up in real life and online over the last year or so, and also at other eco-activist exhibitions around Europe, but only now, finally, in London.

[image4]

It is worth repeating this insight from my interview with Pietroiusti, in response to the question of the artist’s role in environmental justice: “I think we all start from the principle that the role of art in the environmental field is almost like public understanding and public dissemination. How do you make data powerful or beautiful or emotional or sensible? How do you make it visceral?”

It certainly feels visceral in here, what with these immersive smells, sounds and sights. But there is a lot more to the works than sensory stimulation. Rezaire and Agbo-Ola’s installation works on many levels. The wooden frame (recycled from previous display structures used at the Serpentine) is inspired by the body of an ant, in tribute to this tiny insect’s crucial role in distributing seeds and aerating soil to keep it healthy. The knitted panels of dyed cotton on to which the dried plants are stitched are arranged to cast shadows that resemble leaves.

[image5]

The plants themselves are those used by the Rezaire in her practice as a doula/midwife and are chosen for their healing as well as aromatherapeutic properties, which will change as the plants dry. At the centre of the work, a speaker emits a soundscape that the artists describe as “an aural expression of the interconnectivity between body, energy and earth”. Its skill at summoning that quality is a hard one on which to provide accurate feedback, especially in the evening’s party atmosphere.

Eno’s installation is called Making Gardens out of Silence in the Uncanny Valley (2022). Though Eno has established a strong practice as a sound artist – as well as being a rock legend, collaborator with David Bowie and David Byrne, among others – I was not aware of his eco credentials. But he has credentials by the score: he is a trustee of the environmental activist organisation ClientEarth and patron of the global activist platform Videre Est Credere.

[image9]

In aspirational eco fashion, this installation repurposes a sound work he was commissioned to create for last year’s Serpentine Pavilion, which was designed by Johannesburg-based Counterspace. Here, he places the layered landscape of sound (some of which has been generated by computer algorithms, though – as indicated by the Uncanny Valley in the title - it is impossible to tell which came from Eno’s mind and which from a computer program), within a darkened brick archway lit by the aforementioned flickering but flame-free candles. It is well worth tuning in to Eno’s podcast on the work, made available on the Serpentine’s Back to Earth website which is filled with additional resources. There you will discover that the spatially vast palette of sounds includes some which are sub-audible (“though maybe kids might hear them,” he says). He added these in as “an environmental statement because we imagine that the world was made for us, and we tend not to put any value to the parts of it that we can’t directly see or hear or experience. Yet, in an ecological sense they turn out to be as important as everything else.”

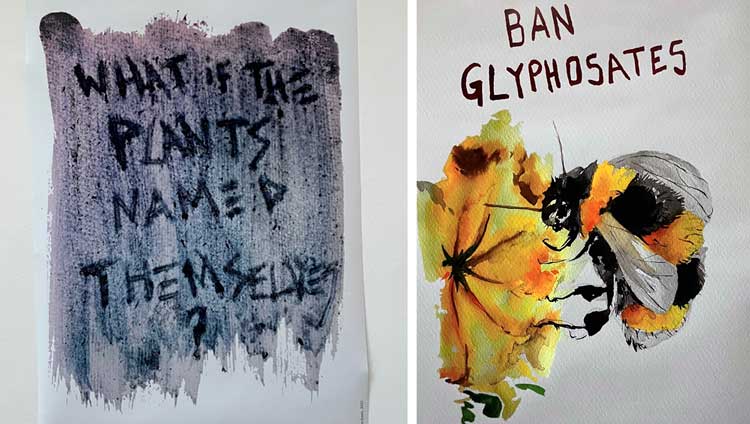

Posters do play a big part in the gallery – there are 33 of them displayed on the interior walls, from artists including Es Devlin, Etel Adnan, Asad Raza and David Adjaye. But they are somewhat overshadowed by Carolina Caycedo’s enormous Google Earth-style wallpaper of giant maps that wraps around the peripheral wall. She is zooming us in to the dammed waterways of South and North America. Above, artist Giles Round’s little models of satellites hover menacingly, echoing the ability of those sinister tools to monitor movements and ecological events for purposes and authorities unknown.

[image6]

Bopape and Tayassu’s earth wall also takes up a fair amount of space, in both its formations: the one being the moist and fragrant barrier/corridor within the gallery and the other a strip of dry mud, adorned with clay offerings, along the floor at the back. The artists say it is “a homage to Earth (created) through the energy of their bodies and the transformation of clay and earth into sonic portraits”. It is easy to mock verbal pretentiousness that often arises when artists describe works that have more craftsmanship in the intention than the execution, but that rudimentary, basic, earthy quality is arguably what makes these works relatable, and it arises out of a research project they are undertaking exploring what they describe as humanity’s “deep kinship” with the soil.

Exploring kinship with land and the hugely problematic legacy we humans have with this precious planet and its inhabitants is very much in evidence in the first gallery, with Karrabing Film Collective’s three-screen work: The Family (A Zombie Movie, 2021), which I was lucky to see also at the Biennale Gherdeina in May. It is a compelling but entertaining journey through stories of colonisation, land exploitation and plastic pollution, with the one white member of their indigenous Australian collective playing the mud-smeared, drooling and polluting “zombie” of the title.

So far, so visceral – as Pietroiusti wanted. There is a work taking its place in what is usually the gallery shop, which steps back from that sensory engagement, however, and initially feels a little flat in comparison. It is by Superflux, in collaboration with Studio Ghazaal Vojdani, titled: It’s easier to imagine the End of Capitalism than the End of the World (22.06.22). When you take a closer look, it packs just as much punch as some of the more tactile work around it. Attempting to “point to the interconnectedness of capitalism and climate change”, instead of filling the shelves with the usual gallery boutique baubles - every bit as extractive and exploitative and useless as the majority of stuff peddled to us in the name of capitalism - they have assembled books by leading thinkers, products that are designed through circular economy principles, and surrounded them with shiny silver manifesto posters suggesting how we can change our consuming habits. The display furniture is from a range by the Italian designer Enzo Mari from his pioneering 1970s open-source Autoprogettazione? (self-design) project, which posits: “Every aspect of our lives can be viewed as an opportunity to reconsider our relationship to the planet.”

[image7]

There are more works sprinkled around the venue and further afield in London. There is, for example, a Climavore menu devised by Cooking Sections in the Magazine Café. And stepping back to the pollinators who make our food production possible, we have Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg and her Pollinator Pathmaker project – a living sculpture in the form of 11 flowerbeds along the northern edge of Hyde Park, in Kensington Gardens, made up of plants chosen not for their aesthetic appeal to humans but for their potential to attract and nourish the pollinators. It was commissioned by the Eden Project in Cornwall, initially, but is now embarking on its journey around a variety of public parks.

Will people wander up to Kensington Gardens to take a look? If they do, they should brace themselves, as Ginsberg explained to me, for the fact that: “The garden in Hyde Park is not impressive because part of it hasn’t been planted. For some plants, we have to wait for September when it’s cooled down. And some plants have been eaten by squirrels.” And that’s OK, she says. In this way, it’s the essence of a slow and participatory artwork. Nature will interact with it in its own way.

This bold, long-term project stems from Ginsberg’s research into how pollinators see the world, what attracts them in the way of plant colouring, form and fragrance. “I was thinking: what does a garden look like to these primary users? If you created a garden for pollinators, what would it be.” Using the available scientific research, she designed an algorithm to try to answer that question. “But also to buffer from human taste, so I wouldn’t get distracted by arranging plants in aesthetic ways. I am asking if the technology can actually be used for pollinators’ benefit.” The 11 flowerbeds may hold an answer. But a major part of Ginsberg’s artwork here is public participation. She has designed a Pollinator Pathmaker digital tool that anyone can access from the website, so they can either create their own digital pollinator artwork, if they don’t have a garden, or try it out in their own back yard. It is the essence of open source and, as she says, radical in its approach.

Ginsberg is hoping for more public garden commissions. This is the second, with the Eden project’s 55-metre-long pathway, planted last autumn, still taking shape as “a billboard of strangeness”, as Ginsberg hopes. “I hope it looks odd. That’s the problem: if it looks tasteful, it won’t stand out.” She hopes the project will be compelling enough to inspire communities to take up the challenge and create their own. “Can we persuade schools that this is the garden project their pupils should be doing. And can we persuade local councils to turn a roundabout into a pollinator pathmaker garden? That whole process transforms the consumer of the artwork into an activist.”

This artwork is remarkable, in that it could make a difference – to help stave off the decimation of the flying-insect population. Apparently, 75% of that population has disappeared in the industrially farmed areas of Germany; a figure likely to be much the same across Europe.

[image8]

One of the works I was most delighted to see as part of the off-site programme – reappearing after its Golden Lion win for Lithuania at the 2019 Venice Biennale – is Sun & Sea, an eco-opera that ran for two weeks at the Albany in Deptford, south-east London, in conjunction with London International Festival of Theatre. An eco-opera by artist and musician Lina Lapelytė, librettist Vaiva Grainytė and director Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, it recreates an actual beach, on which sunbathers, holidaymakers, dogs and children perform their seemingly idyllic beachside rituals while singing about love, loss, work and play, and slowly, seductively, flagging up the constructed – and globally polluting - nature of our attitude to leisure.

Back to Earth is a courageous and uplifting offering, full of interest, enjoyment, and heartfelt artistic offerings, encompassing craftsmanship and concepts both ancient and cutting edge. Check out the multiple events and talks that are in the programme. I leave the concluding words to Eno, from the aforementioned podcast. “Any piece of art is saying pay attention to something. If it’s a novel, it’s paying attention to this person’s emotions. What I think we’re doing here is saying: ‘Pay attention to the world around you.’”

• In addition to Lucia Pietroiusti, strategic consultant, ecology, and founder, general ecology, the curatorial team for Back to Earth comprised: Sarah Hamed, assistant exhibitions curator; Rebecca Lewin, curator, exhibitions and design; Hans Ulrich Obrist, artistic director; Kostas Stasinopoulos, associate curator, live programmes; Jo Paton, former chief producer; and Holly Shuttleworth, former producer.

,-2021-2022.jpg)