by DARRAN ANDERSON

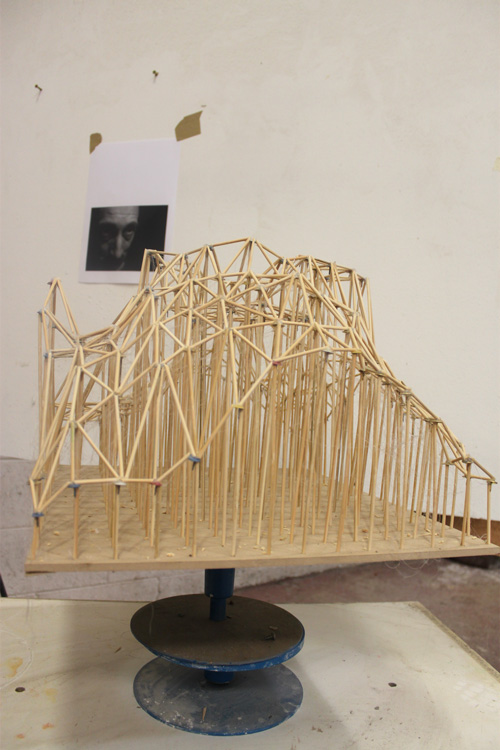

Niamh McCann’s art is alive with resonances and paradoxes. It appears as protean as the world it is assembled from and yet it feels self-contained; capturing a plurality of ideas and echoes with still, totemic clarity. Her latest collection of works, Just Left of Copernicus, was inspired partly by the German architect Hans Poelzig, who died in 1936. The exhibition, currently on show at the Visual Centre for Contemporary Art in Carlow, will travel to other parts of Ireland next year.Profoundly concerned with space and perception, it will adapt in response to each gallery setting.

Darran Anderson: Your latest work references Hans Poelzig, an astonishing German expressionist, whose Grosses Schauspielhaus with its artificial stalactites seems a tantalising, largely untaken, path in architecture. What drew you to him?

Niamh McCann: I have looked at much of the Poelzig material held in archives. The photographs and drawings relating to the Grosses Schauspielhaus are tantalising, even by virtue of the fact that the photographs are in black and white, and a selection of the drawings [is] in colour. In combination, the somewhat abstracted drawings give a sense of the use of colour adding to the structural drama.

The film architecture of the The Golem: How He Came into the World (1920), for which Poelzig was a scenographer, is in many ways the most visible and available residue of his use of structural space as an embodiment of emotional and psychological narrative. His famed IG Farben building, or Poelzig Complex, is markedly different for its sober lines and deliberate symmetry. That said, I imagine the effect of entering the pompous lobby of the Frankfurt building being comparable to the dramatic effect of being in the Schauspielhaus dome space – all light and height, artificial and otherwise, married to a hyper-awareness of the specificity of material and pattern. Differing visual languages, but perhaps similar psychological undergrowth. I could be wrong. Tantalising…

I tripped across Poelzig. I was following a thread of Bauhaus and pre-Bauhaus designers and makers, to no real end, to-ing and froing between images and textual information, when I came across some images of the Grosses Schauspielhaus and interior photographs of Haus des Rundfunks, Berlin. Before this I had not been aware of Poelzig, yet even a precursory scan through online material begins to unveil a breadth of produced work and depth of impact. He was an influential member in the early incarnation of Deutscher Werkbund, an organisation central in the development of the Modern and, of course, subsequently in the creation of the Bauhaus school of design (and thus beyond). He worked as a scenographer with [the actor, writer and director] Paul Wegener, on a number of films, most famously The Golem. He designed to production a number of buildings, including the IG Farben building, a nexus of pivotal 20th-century events. A hop and a skip will bring you to the The Black Cat, a 1934 Universal Pictures production in which Boris Karloff plays the protagonist, a satanic high priest called Hjalmar Poelzig. The director dubiously claimed to have worked with Poelzig on The Golem.

This arrested my attention for a number of reasons. First, I think it really interesting that we have an assumed commonality of information and visual and/or cultural history, particularly from a western cultural perspective, and yet the lived experience or idea of modernity as one trope is very different in Germany from the encounter with the same information in, for example, Ireland. I am drawn to this parallax of perspective. I am interested in how certain visual debris survives and continues to evolve even when separated from initiating ideology.

Second, I find it fascinating that Poelzig was so present in so many narratives – developing through expressionism and new objectivity to rest on a more pared-back style, crossing forms of production and creating the location for particular events. Yet if one were to think of these events as a series of snapshots or photographs, he would be to the left of centre of the image rather than the absolute focus.

Finally, I love the rolling together of fact and fiction, the overlapping layers of narrative, history and fable that are contained within the cultural and physical structures that we construct. Karloff is Hjalmar Polezig.

DA: Collage has a particularly interesting function in your work, recontextualising the familiar, provoking associations and stirring questions. Are you conscious of the viewer when you create your work? Is collage effective because it’s closest to how the world actually is or how we perceive it? Or is it something more dissonant?

NMC: I would like to return here to the idea of parallax. We can, for the most part, settle on the central presence of a mutually agreed subject matter or more simply subject. However, we bring to that viewing a parallax of personal or geographical subjectivity. I think that collage by its structure can accommodate those two perspectives.

The world is dissonant and vast. Editing and discarding information is necessary in any attempt to understand and survive the deluge. In that respect, the collage form is accurate in its own way, making new landscapes of information or images as a form of examination – for me, the device of taking the familiar and reforming it is an effective tool for the questioning and testing of underlying assumptions.

I think that one is always conscious of the viewer. We are our own first audience, after all, and the process of making involves a continual assessment of composition and placement, inhabiting the dual position of producer and viewer, in preparation for that other that one hopes will enter that space.

DA: On a related note, I really like how you have taken Yves Klein blue and re-envisaged it through your work. It seems such a trademark, yet you have brought it back to life. What was it about it or its creator that attracted you? Is it liberating to reference earlier works?

NMC: Referencing earlier works can be liberating. It can also give you access to an a priori set of associations and inferences. In this way, Klein could use a chemically balanced, unsullied ultramarine pigment and claim it as his own, while simultaneously making reference to the sumptuous lapis lazuli of the medieval Madonna and its attendant critique on hierarchy of value. I find Klein’s grandiosity vaguely funny. In truth, he owned neither the sky nor a blue. Saut dans le Vide was not evidence of unaided lunar travel. And yet, I believe his sincerity. I believe in his testing of the parameters of certain propositions, his probing at the edges of his own landscape.

When I have used ultramarine pigment suspended in medium, I have done so not in some desire for a “unity of single colour”, but rather as a device to disturb and interrupt the visual space. I am not speaking of sky, but of the making of artifice. For me, the horizon of our artificial, created landscape is no less real than the line between sky and land.

DA: You seem to leave considerable room in your art for chance. Is that a subject that interests you?

NMC: I think of it more as reactive rather than presumptive thinking – in other words, being sensitive to, and allowing, a material or form to take its own path. Genuine explorative thinking has an open-ended quality, reactive to outcomes and, therefore, always with an element of chance – a curiosity as to what is going to happen. I also think that failure is a very interesting subject. Most progress, from small instances of personal learning to grander examples, is achieved through a process of attrition.

However, there is control there also: through practice, repetition and experience one finds out where the faultlines are and allows that to become part of a work. And, of course, not all works are shown. There is a lot of editing and trial of materials.

DA: How important is the political to your work? Can it have a deadening effect on art if approached too directly?

NMC: I find it pretty impossible to avoid constructed thought; the circular relationship between the shaping of our environment and having it shape us in return. We own that responsibility and a testing of this is political. However, while finding those notions crucial to the process of making, I am nervous to the point of antipathy of the polemical. I am much more interested in looking at faultlines and nodes of contact across divides, and doing this from my own idiosyncratic perspective.

I mean, it seems all too easy to me to be subsumed by subject matter, particularly in the area of institutional critique. Poetry, association and chance can articulate questions and hold ideas to account using less direct routes.

DA: You work across multiple media, yet your voice never seems unintentionally disjointed. Do you find the different methods exert their own influences? Is there a sense of translating your art through various mediums?

NMC: It is natural for me to work across mediums. There is interior logic to materials and their marriage to ideas. I can use a specific blue in a specific material and that will naturally take one along certain lines of thought. Each choice of medium takes its own route and, when it is all working well, the line between the exploratory thought and the chosen medium is seamless. Art in general is, I believe, an act of translation, the act of externalising a thought process through a chosen medium or situation. I like the idea of looking at facets of the same thing and pushing it through different mediums.

I think it also worthwhile to point out that I enjoy the process of making and the specific luxury of materials. I consider making a (perhaps undervalued) form of thinking. Poelzig, as a teacher at the Breslau Academy of Art and the Technical University of Berlin, taught making as the true test of one’s ideas.

DA: You seem particularly attuned to influences from all over the globe and through time. Is it important for you to roam in terms of place and subject?

NMC: We so often share common ground and pools of information, yet approach this commonality from different directions. In taking this common difference as subject, it is natural to roam through those influences over non-linear times and locations.

DA: I get the sense from your current work (as well as earlier projects such as Tiltshift) that history is not entirely dead or finished, but rather it is an ever-changing thing, subject to perspective and retrieval. How do you view the past via your work?

NMC: I look at subjects that are still current or, more particularly, elements that retain some cultural currency. It is curious how certain images, objects, methods of making or stories survive and live on whereas others fade. This cultural debris can be revealing. Things may be distanced by time from a certain context or ideology, but still be present in vernacular culture, retaining a thread of narrative to its initial incarnation. A building is a building is a building. It is also a sum of events; from the specific social, economic and cultural environment that built it, the person that designed it, the materials, the particular architectural style, the incidents that took place within it, amassing potential for further influence and mythology.

I tease out the parallax in interplay of visual culture and histories and the created environment.

• Niamh McCann: Just Left of Copernicus is on show at Visual Centre for Contemporary Art in Carlow, Ireland until 3 January 2016, followed by Limerick City Gallery of Art (21 January – 24 March 2016) and Solstice Arts Centre, Navan, County Meath, Ireland (1 September – 21 October 2016).