Agnew’s, London

3–26 October 2001

In his foreword to the exhibition, Julian Agnew extolls the virtues of Australian culture:

To those who believe that the three things that Australians love are ‘sport, soap operas and property’, as the Financial Times recently put it, the extent and quality of this cultural activity may come as a surprise. For a population not much larger than that of London, it is extraordinary that there should be such a high proportion of artists, writers, musicians and film makers, not to mention those who read and listen to their work. Within that culture, the visual arts have played a more than proportionate role, perhaps because a young society in an ancient continent has sought to define itself particularly in terms of its unique landscape. Because of its importance as a defining element of ‘Australianess’, Australian painting has been enormously popular in that country but conversely comparatively unknown internationally.1

[image1]

The only significant drawback with the Agnew’s exhibition is the fact that it is not bigger and more comprehensive. Not that that is a criticism of the show, but of the broader question of overseas representation of Australian Art in London. Since Bryan Robertson’s Whitechapel Art Gallery’s ambitious, ‘Recent Australian Painting’ in 1961 (111 works by 55 artists) and a larger show still at the Tate in 1963, there has not been the sustained interest in Australian art. Certain commercial galleries have represented Australian artists, most notably Marlborough Fine Art, Fischer Art and more recently the Rebecca Hossack Gallery. The best Australian artists have traditionally shown in London and their status in Australia is defined in part by their success and reception in London. Artists such as Arthur Boyd and Sir Sidney Nolan spent most of their careers in Britain.

In the 1960s Australian art arrived in Britain at a point where its appeal lay to a great extent in the fact that the artists represented painted landscape, and they did so in a way that such a persistently Ancien Regime would find thrilling. The Tate show catalogue had a foreword by Sir Kenneth Clark; by contrast to ‘Civilisation’, the Australian painters presented an uncivilised world which critics described as, ‘direct’, ‘tough’, ‘bold’, ‘fresh’. The New World images could thus purge the ills of the Old. One would have expected that with individuals such as Bryan Robertson (the Director of the Whitechapel) and Sir Kenneth Clark championing Australian contemporary art, the narrative would have been sustained. Alas, the 1970s were a period of individual exhibitions but little comprehensive representation. It was not until the 1988 Australian bicentennial shows: ‘The Angry Penguins’ at the Hayward Gallery and ‘Stories of Australian Art’ (Australian art in British Collections) by Jonathan Watkins that Australian art was presented as such. In Nicholas Usherwood’s introduction to the Agnew’s exhibition he points out that the 1961 Whitechapel show was attempting to pigeon-hole Australian art and the fact that it proved impossible meant that it fell from the public gaze

This was part of an identity crisis which reflected what was happening in Australia itself as huge arguments and discussions raged between figurative artists and abstractionists, or ‘Australian art versus Internationalism’ as it was often painted by its adversaries.2

The greatest discernible influence of American art during the 1970s and 1980s was the expansion in art practice to include photography, land art, body art and installation. In such a climate it was possible for white Australian (European derived) culture to interact more meaningfully with Aboriginal culture. As the Agnew’s exhibition reveals, early images of Aborigines by Russell Drysdale (Arthur Boyd’s ‘Half-caste Bride’ series could not, alas, be included) present the dispossessed Aborigines in a warm and sympathetic light. Most city dwellers in the 1950s in Australia had not even seen Aborigines; the two cultures remained separate though both author Patrick White and artist Arthur Boyd presented their tragic plight sympathetically and with a seering tone.

Fred Williams abstracted landscapes, for example, ‘Evening, Karratha’ (1979) from his Pilbara series. Williams was described by Anne Gray (University of Western Australia) ‘as one of the few non-Aboriginal artists whose paintings capture the essence of the far north-west. Unlike Drysdale and Nolan who viewed the outback as an inherently vast, remote and alien landscape, Williams showed the Pilbara as an accessible and often joyous place’.3

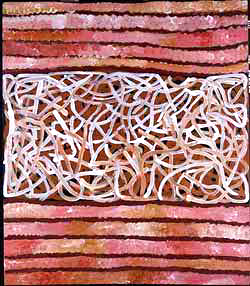

Agnew had not originally intended to include any Aboriginal artists until he was ‘seduced by the colour sense and charm of Emily Kame Kngwarreye’, ‘the 80-year-old woman brought up in the central Australian desert’. She is the only Aboriginal artist (and only one of two women artists) who has produced ‘an art which has taken the aesthetic of abstract expressionism to come to terms with’.4

Emily Kame Kngwarraye’s work in this show marks part of the beginning of a process which, by the mid 1990s with the Aratjara show at the Hayward Gallery (1993), saw Aboriginal art in a contemporary mode being displayed, without any attempt at differentiation, alongside work made relatively independent of European art, that is, within a general idea of contemporary art that, as John MacDonald observed at the time, allows each art object to be defined according to its own particular history and the identity of the artist.5

The case of Emily (1910–96) is central to the emergence of Aboriginal art in a contemporary context. She belonged to the Woman’s Batik Group at the Utopia Ranch in the eastern desert (north-east of Alice Springs) in 1978. She started painting in the 1980s when she was in her seventies. Her career only lasted ten years and in that time ‘she rapidly established herself as one of the leading artists in the renaissance of Aboriginal art at that time’.6

The work of Emily differs significantly to the more familiar Papunya and other central and western desert groups. Painting in the eastern desert region is an almost all-female activity (as opposed to senior men) and ‘Its roots lie in Indonesian batik and body painting rather than sand painting. For it was out of the rich strand of traditional designs associated with the body-painting applied to women’s arms, breasts, and legs before the traditional awelye dreaming ceremonies and so enthusiastically adapted by the Utopia women to silk batiks, that came their first public and critical success in the early 1980s’.7

Emily Kngwarreye emerged as the central figure when the group first used acrylic paint on canvas in the late eighties. Usherwood describes her painting ‘Bush Yam’.

‘It is also a painting without a ‘right’ way up; desert painting being done seated beside or even in the middle of the canvas laid on the ground, as well as suggesting the descent of fluid paint on to ‘the country’ of the painting that provides such a potent poetic/visual metaphor for the descent of the fertilising rain, quite simply makes such considerations irrelevant. Seeing her art as her way of ‘looking after’ her country and thus ensuring its continuing fertility, the radical artistic developments embodied in Kngwarreye’s art can also be seen as reflecting the huge changes that have taken place in recent years to the natural environment out of which these paintings so profoundly and intuitively spring and form part.’8

Emily is only known to have made one statement about her painting. ‘Whole lot, that’s all, whole lot, awelye (Dreaming), arlatyeye (pencil yam), ankcerrthe (mountain devil lizard), ntange (grass seed), dingo, ankerre (emu), intekwe (small plant, emu food), atnwerle (green bean) and kame (yam seed). That’s what I want to paint: whole lot.’9

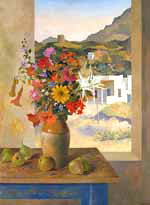

Although constrained as a commercial gallery by the availability of work for sale at any given time, Agnew’s exhibition was refreshing in that it included artists lesser known here in Britain, who do not fit into the pigeon-hole of brash or fresh landscape artists. The subtle still-life work of Justin O’Brien is included, abstract work by Melbourne artist Roger Kemp, the complex still-life with surreal humour of John Brack and the interiors of Brian Dunlop.

In the context of the exhibition’s title ‘You Beaut Country’, one of Australia’s more influential artists John Olsen is included. He has made many journeys to central Australia and published diaries and paintings which reveal the dialogue he has with the land, Aboriginal ways of seeing, and with formal preoccupations such as those learned from the work of Spanish painter Tapies. His work has a calligraphic quality and a high-pitched tonality. Olsen combines an intricate and highly charged mark-making process with a Zen state of being which reflects his long interest in abstraction and Eastern thought.

Agnew’s exhibited ‘Nolan’s Nolans’ in 1997, for which Nicholas Usherwood also wrote the catalogue. Nolan is, therefore, better represented than any other artist with 13 paintings. Sir Sidney Nolan settled in London (more or less permanently) in 1953. Following the Second World War – which had made travel impossible – the late 1940s and 1950s saw a veritable exodus of artists and writers from Australia to Europe; mostly to London. The war years have, over the past 20 years, been well documented; the enforced isolation of artists has generally been thought to have had a positive effect on artists who had to rely on their own resources, the physical shortage of materials being a case in point. Artists were forced to be inventive and resourceful with a shortage of canvas, paint and artists’ quality paper. They often made their own paints from traditional recipes or experimented with ‘new’ paints from ICI (Nolan, Tucker, Boyd) such as polyvinyl acetate which Nolan continued to use in the 1950s for his ‘Gallipoli’ series. ‘Myth Rider’ shows a strange, helmeted ‘soldier’ and was one of the early works in the series that was produced up until 1963 in large oil on canvas works.

Nolan and his wife Cynthia were living on the Greek Island of Hydra in 1957 where he became interested in Homer’s Iliad and Robert Graves’s Greek Mythology. He became interested in linking the Trojan wars with the Gallipoli campaign of 1915 which left a profound mark on Australian consciousness and history. Also on Hydra at the time was the Australian writer George Johnson and on nearby Spetsai, Alan Moorhead. George Johnson commented on the fact that Gallipoli was fought on the same ground as the Trojan wars; the idea, he said, was ‘… like unlocking the door. We would talk far into the night about this other myth of our own, so uniquely Australian and yet so close to that more ancient myth of Homer’s. Nolan’s poetic imagination saw them as one, saw many things fused into a single poetic truth, lying as the true myth should, outside time’.10

The major omission from this exhibition is Arthur Boyd who was Sidney Nolan’s brother-in-law (Nolan married Mary Boyd). Both strove to paint distinctly Australian, iconic works of art and both achieved great stature in their work with international acclaim. Boyd mythologised the Australian landscape and he wove classical mythology and Biblical imagery to create images of a world shorn of all hope, apocalyptic images following the Second World War, Breugelesque worldscapes with references to literature, art historical sources and autobiography. In 1963 Boyd had a large retrospective (aged 43) at the Whitechapel Gallery followed by another spectacular show in Edinburgh in 1967 at the Demarco Gallery. Among Boyd’s most remarkable works were his ‘Half-Caste Bride’ series in which he depicted the plight of dispossessed Aborigines. They were painted following a trip to Alice Springs in 1956.

Following the closure of Fischer Fine Art in 1991, Boyd was not shown in London (except for the odd print exhibition) until last year – to mark Australia’s federation (1901). The exhibition, which had already travelled around Australia, arrived at Australia House. It was in large part, if not in toto, the 1972 exhibition at Fischer Fine Art in London. Raw, seering, grotesque images indicated the artist’s inner turmoil – and whether they are interpreted in Freudian terms as critic Tom Rosenthal advocates, or as symptomatic of a general artworld dilemma, these works are difficult to say the least. And so they did not sell well but were included in the Arthur Boyd gift (1975) – thousands of works of art worth millions of dollars – to the Australian National Gallery. They were accompanied by a superb and priceless collection of works in all media, from all periods of his oeuvre.

The exhibition of Arthur Boyd at Australia House last summer was, as Grazia Gunn commented in her review for the Times Literary Supplement ‘a missed opportunity’. Gunn was the curator of the Boyd gift in the 1970s and she devoted much effort to presenting Boyd’s work to the Australian public in the form of travelling exhibitions such as ‘Seven Persistent Images’ (1985). ‘The Caged Painter’ works of 1970–72 dominated the poorly curated exhibition that was accompanied by an unscholarly catalogue essay. If that is how the London public remember the work of Arthur Boyd, then no wonder a work could not be found for the Agnew’s show. It seems ironic that, by contrast, a commercial gallery in London can produce an excellent, scholarly catalogue when the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) and Australia House between them have failed.

The exhibition at Agnew’s comes, therefore, at an opportune moment. Despite the remarkable vitality of yet another generation of young painters today, there appears to be no apparent move afoot by the NGA to bring their work to Europe. In the 1980s there was a surge of well-curated, scholarly and informative exhibitions showing modern and contemporary Australian painting, not only in London but in Paris and New York. In the present void, Julian Agnew has reminded London of the brilliant range of talent which later 20th century Australian painting can offer, and of the evident continuing interest and commitment of European collectors. What is now needed is, given the substantial funding still available to exporting NGA exhibitions, for a major new cultural initiative in this direction, purpose-made to celebrate the federation year and, more importantly, the new talent available in this millennium.

Footnotes:

1, Julian Agnew. Foreword. In: You Beaut country, A Selection of Australian Paintings 1940–2000. London: Agnew’s 3–26 October, 2001, no pagination.

2. Nicholas Usherwood, Introduction, ibid.

3. Quoted, ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. Quoted, ibid.