Waddington Custot, London

17 May – 30 June 2019

by VERONICA SIMPSON

“If one draws things in a manner which provides only the barest clue to their meaning, the viewer is forced to fill in the gaps by using his own imagination … He is compelled to participate in the creative act, which I consider very important.” In the course of researching this show, the above quote from the Spanish painter Antoni Tàpies (1923-2012) struck a chord, not only because of the way in which his cryptic, zen-like works incorporating signs, symbols and all manner of found materials deliver exactly that kind of sticky lure to the imagination, but also because a major part of the attraction of graffiti - which is the focus of this exhibition – is both the mysterious meaning and the provenance of the random marks made on our cities’ streets, walls and structures. The scratches, drawings, bulletholes, pits and pockmarks, are layered like scar tissue over the urban realm, and we can’t help but be curious about their creation.

[image2]

Waddington Custot’s show Writings on the Wall is a tribute to a cluster of 20th-century artists, including Tàpies, whose work was directly inspired by ghettoised or street-art forms - systems of self-expression that evolved outside the tasteful confines of the gallery or museum.

[image4]

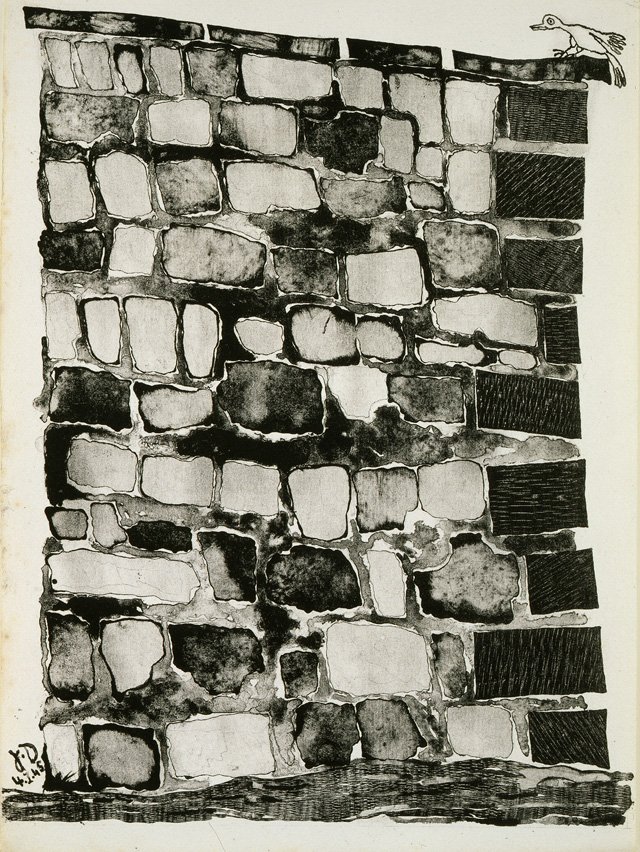

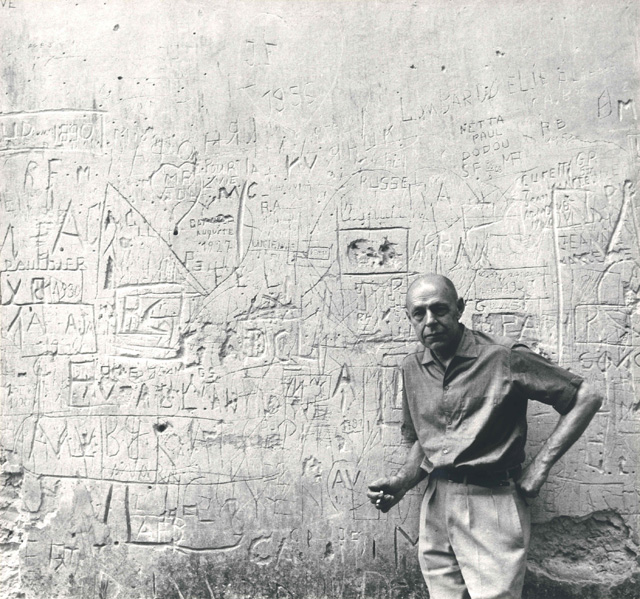

This mini-movement can be traced to the photography of Brassaï (born Gyula Halász; 1899-1984), whose camera captured the scrawls of strangers over the walls of Paris between 1930 and 1960. These images apparently inspired a series of lithographs, Les Murs (The Walls), among other works, by Jean Dubuffet (1901-85), as well as triggering a response from Tàpies, who evolved a system of mark-making that seemed to fuse elements of primitive cave art and mathematical symbols with modern and ancient graffiti – elements integral to the work of another Spaniard, Manolo Millares (1926-72) as well as Cy Twombly (1928- 2011).

[image7]

Having established that common thread between these artists, what the curatorial team, together with emerging young London architects IF_DO, have done here, with their inspired selection and staging, is bring these connections and enthusiasms, and the era in which they emerged, vividly to life. Within the usually restrained white-walled Cork Street gallery, we are brought, at the entrance, right into that mid-century moment around which these works pivot: to the right is a wall of seemingly board-marked concrete on which the names of the artists are written, black on pale grey. That same concrete finish continues into three walls of the next room to become the backdrop for three of Twombly’s more ethereal, provisional sketched works, plus two spotlit paintings by the sixth artist in the show, Greek painter Vlassis Caniaris (1928-2011).

[image13]

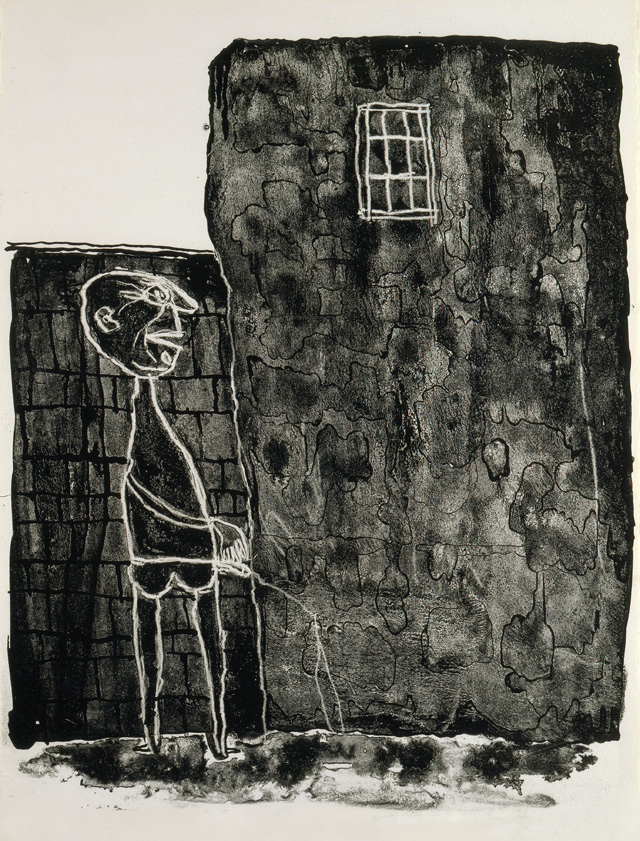

His Homage to the Walls of Athens 1941-19… (1959) reflects Caniaris’s experience of the civil war that followed the occupation of Greece after the second world war. The interior, fourth wall, however, is painted a dense, matt black, against which are six of Dubuffet’s aforementioned 1945 lithographs; penile cartoons, men pissing in alleyways, the cumulative scars of a thousand scrawled initials, it’s all here - the very essence of urban, illicit (male) rebellion.

[image14]

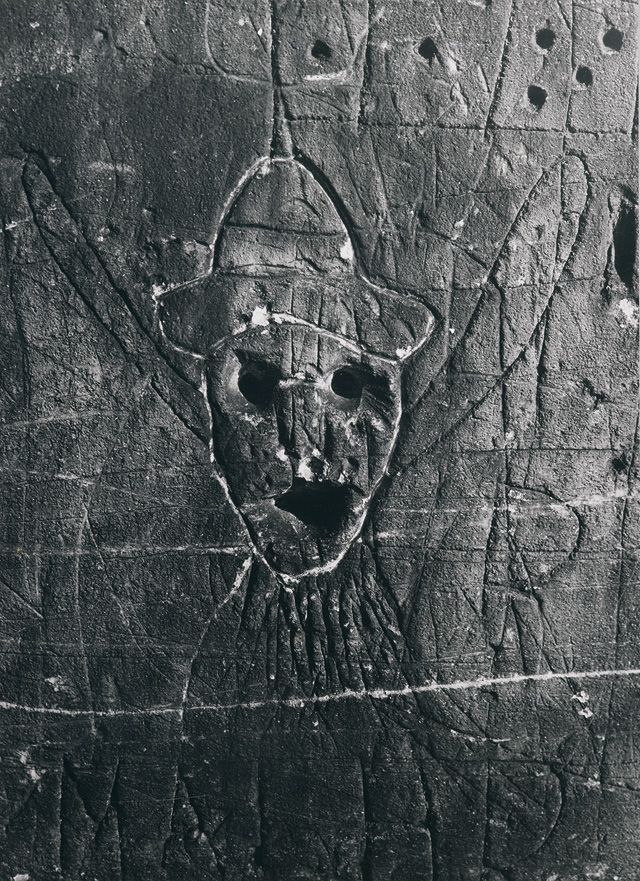

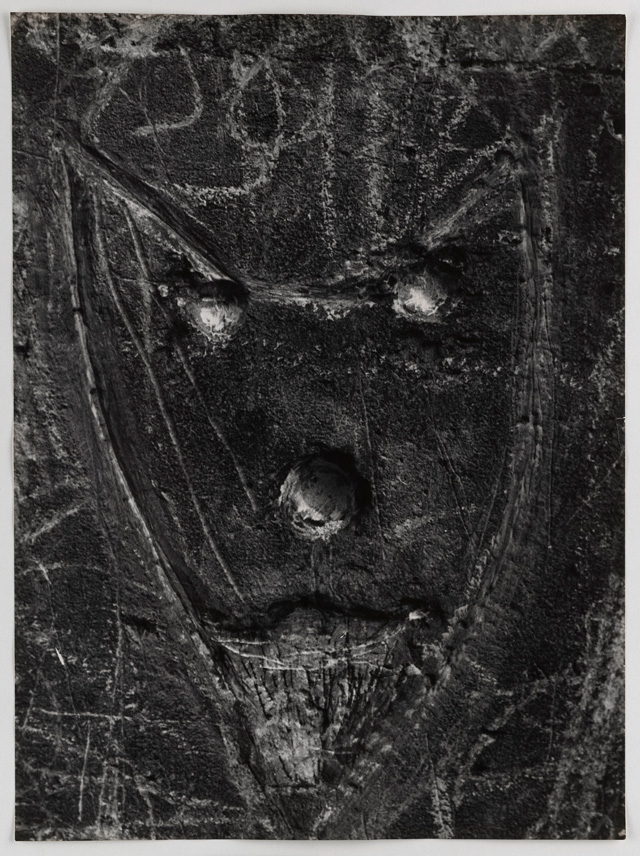

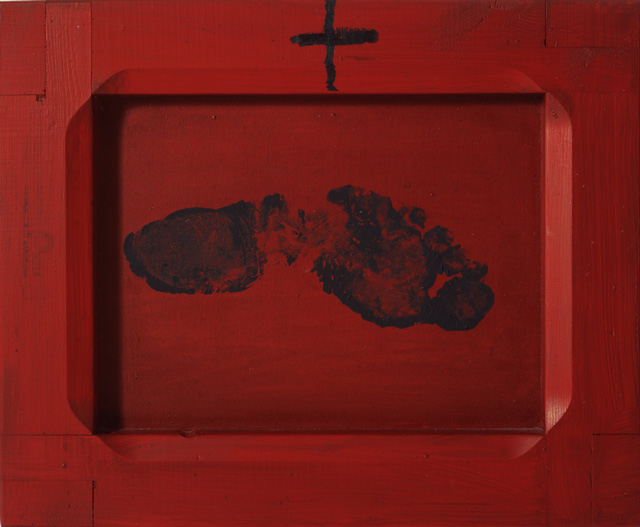

This black wall, which slices across what is normally one large gallery space, is interrupted in two places: a slender crack reveals the Dubuffet works beyond, and another, which is more of a chasm, the entrance to a dark corridor. The descent into darkness is entirely in keeping with a sense of moving into a cave-like space, evoking the ancient instincts that underpin our urge to scratch symbols on our surrounding surfaces. While the left side is empty, a black void, the right is host to some of those original, inspirational Brassaï photographs. Travelling up this corridor feels somehow ceremonial, quasi-religious, an effect enhanced by the demonic faces that start to appear in Brassaï’s images as you reach the wall’s end, and consolidated by a single, small, but powerful, blood-red picture of Tàpies placed, dead centre, against the white end wall. The cross marked into the top of this picture sings out in alignment (or close enough) with the crosses on three other Tàpies works assembled in the adjacent room on the right.

[image5]

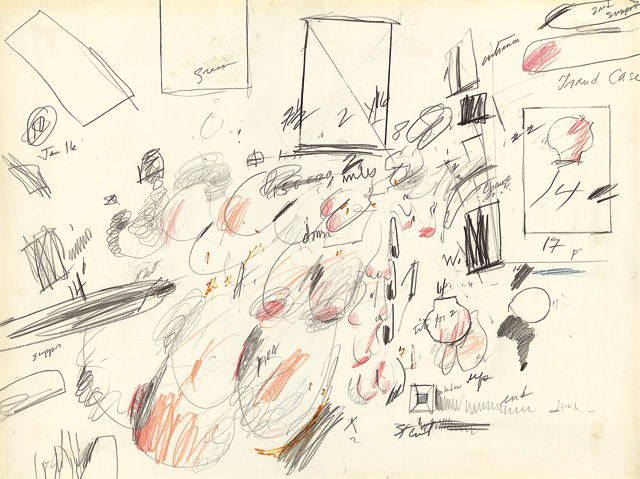

Here, we move out of the temple and into a space more evocative of the schoolroom, thanks to a wooden bench placed in the centre of this paler, brighter room. Riffing off the lines of semi-legible script – numerals, symbols, runic scribbles – in Tàpies nearest work, Signes sobre matèria/Signs on matter (2006), this bench puts the viewer in perfect alignment to admire the huge, crumbling drift of reddish-brown dirt that adorns the adjacent work, Aixeta/Tap (2003). This is the real star exhibit in the room, the titular tap protruding from the top righthand of the painting; art as infrastructure.

[image9]

The final room, across the corridor from the Tàpies grouping that in many ways forms the heart of the exhibition, is an angular, provisional space, with two particularly gorgeous, glowing Dubuffets at its heart: the pirouetting, crisscrossing red and blue lines of Mire G72 (Boléro), 15 Mai 1983 (1983) and its grey-and-blue counterpart, Fantasme bleu, 8 Mai 1984 (1984). This is mark-making truly liberated from the constraints of context, an evolutionary leap from the graffiti/cartoon/cave painting companion work from 20 years earlier that sits more quietly on the adjacent wall, La Chasse au Biscorne (EG 77) 19 Août 1963 (1963).

[image10]

It is interesting that London is missing from the cities conjured or represented in these works - Paris, Barcelona, Athens, Rome – but the language is universal. And the spirit of grassroots, even antique protest, certainly speaks to our times: most of these artists having lived through at least one global war, one or more civil wars and seen more than enough social conflict.

As Martin Irvine, a professor at Georgetown University, says in the accompanying catalogue: “For these artists, the city is the real teacher, providing a daily instruction manual, a visual encyclopaedia of codes and semiotic systems, legible on the primary tableaux of urban surfaces.” Perhaps this grouping and presentation has particular traction in London at this time: as high land prices continue to fuel so much speculative development across the city’s heartland, walls and buildings that bear witness to the battles, both national and personal, of the last century or more, are vanishing every day. What we lose with them is the possibility or provocation to imagine the lives of their previous inhabitants – a creative act in which we can no longer participate.

-c1956.jpg)