Royal Academy of Arts, London

24 September – 11 December 2022

by BETH WILLIAMSON

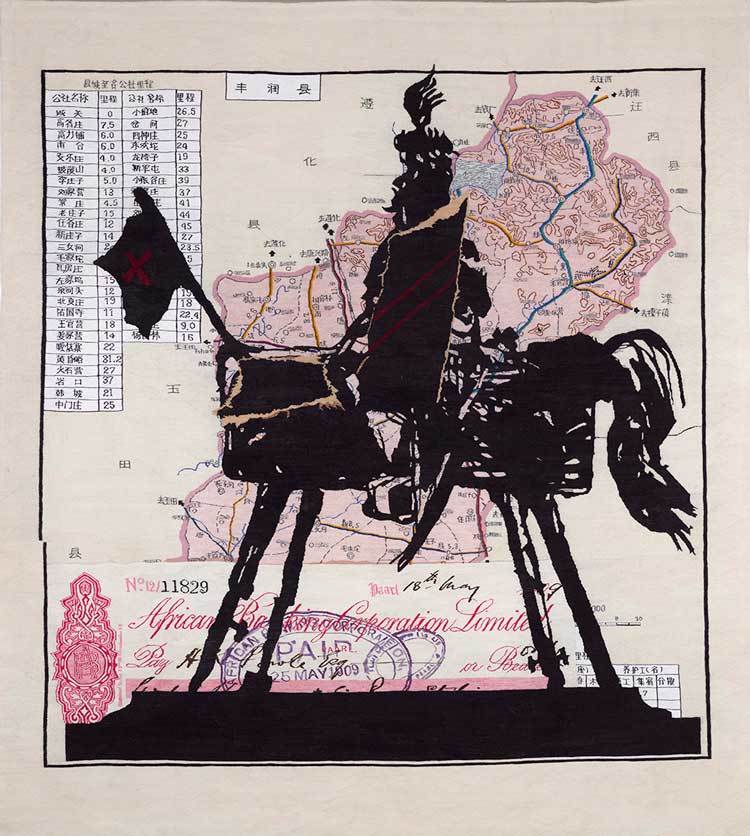

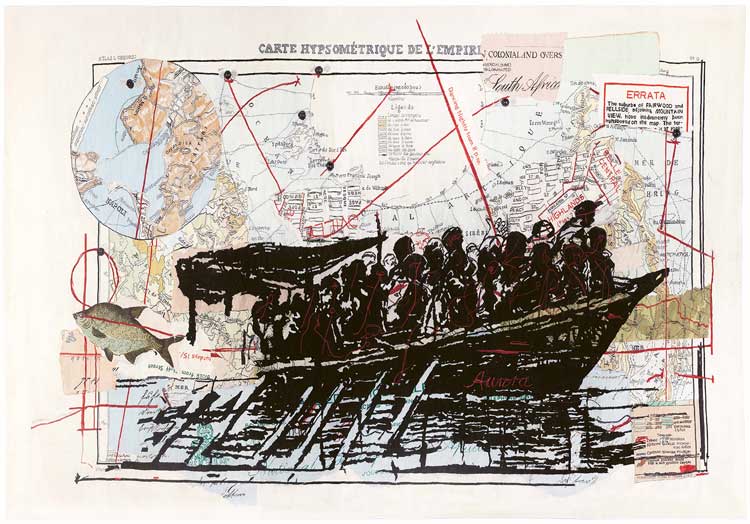

The work of South African artist William Kentridge (b1955) is some of the most powerful you will see. In this, his largest exhibition in the UK to date, we are without doubt taken on an experiential voyage through his work from the last four decades, a voyage that lays bare many of the injustices of pre- and post-apartheid South Africa and beyond. It is a difficult journey, but one that seems to bring viewers together in something approximating an act of witness. The exhibition, like Kentridge’s practice, is rooted in Johannesburg and drawing, but there are prints, sculptures, tapestries and, above all, films and operas. In a panoply of music, monuments and murders, this body of work holds visitors in a space of questioning as they witness the multiple viewpoints of his reflections on exploitation, colonisation, genocide and more.

[image3]

Kentridge’s long history in art and theatre is underpinned by a strong sense of social and political responsibility. That background surely came from a childhood growing up in Johannesburg with parents who were both socially motivated lawyers. His mother, Felicia, co-founded the human rights organisation South Africa Legal Resources Centre and his father, Sydney, defended those, including Nelson Mandela, accused in the Treason Trial (1956-61). In fact, Kentridge himself graduated in political science and African studies at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg before embarking on a formal art education at the Johannesburg Art Foundation in 1976. While still a student, he participated in a protest supporting the Soweto Uprising. Having cut his artistic and political teeth, Kentridge headed to Paris in 1981 to study mime and theatre at the L’Ecole Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq before returning to his hometown.

[image1]

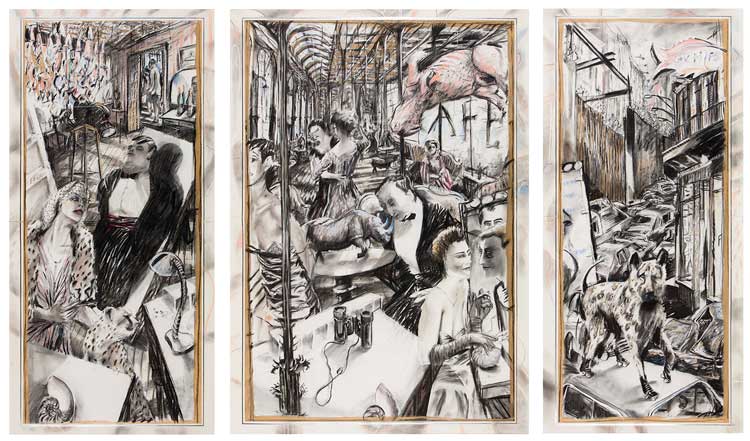

The exhibition begins with Kentridge’s early charcoal and pastel drawings of the 1980s, helpfully providing some important reference points that are carried through the exhibition. Here, the realities of daily life in South Africa under apartheid are exposed. Hyenas, warthogs and cheetahs represent government officials while a burning tyre represents necklacing, a brutal form of execution of black South Africans. There are drawings of armoured people carriers, synonymous with state violence. Juxtaposed with these images of the violent reality facing black South Africans are other drawings of the extravagant indulgences of bourgeois white South Africans. It is a frighteningly stark contrast, but one that has to be made.

[image9]

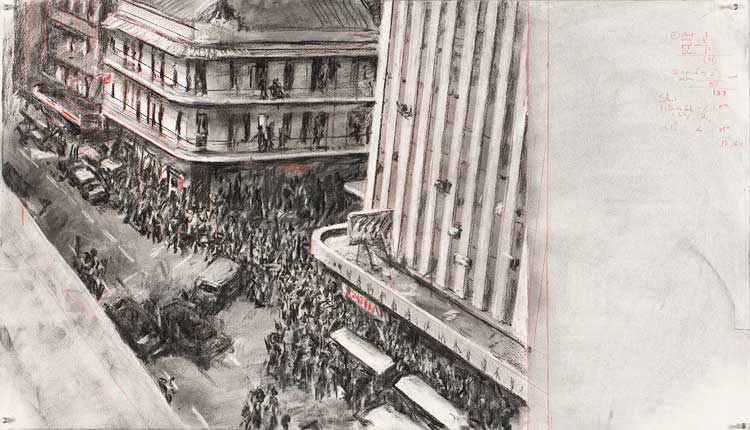

The lens that Kentridge casts over both historical and contemporary events is excoriating, as it should be. As he shifts into film, he also develops his skills as a draughtsman moving from single sheet drawings to much larger, multisheet works. The scope and ambition of his work becomes more expansive, and the subjects become even more difficult. This is Kentridge’s homeland and landscape is central to these semi-autobiographical works. Filled with memory and sadness, the drawings and the films also give way to enormous tapestry works and sculptures, and the activities of the studio itself comes under scrutiny.

The central gallery space in the exhibition is given over entirely to a selection of Kentridge’s Soho films in an impressively inventive fashion that I do not think I have seen previously in any exhibition. Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris (1989), Monument (1990), Tide Table (2003), Other Faces (2011) and City Deep (2020) are all shown. These are just five of the 11 films featuring Kentridge’s protagonist Soho Eckstein, the ruthless founder of a mining town outside Johannesburg. Five screens are hung at different points around the darkened space, each accompanied by one of Kentridge’s signature anthropomorphic projectors, several humanoid megaphones and a handy selection of seating. Almost all the films can be seen from any point in the room. This is not just about creating a space to watch one film at a time, but a space to gather, and to witness everything that Kentridge is dealing with here. There is a sense of common purpose, of sharing these difficult subjects with others in the room in a joint endeavour to negotiate the artist’s complex relationship with his hometown, both historically and in contemporary South Africa. It is a powerful space and experience.

[image2]

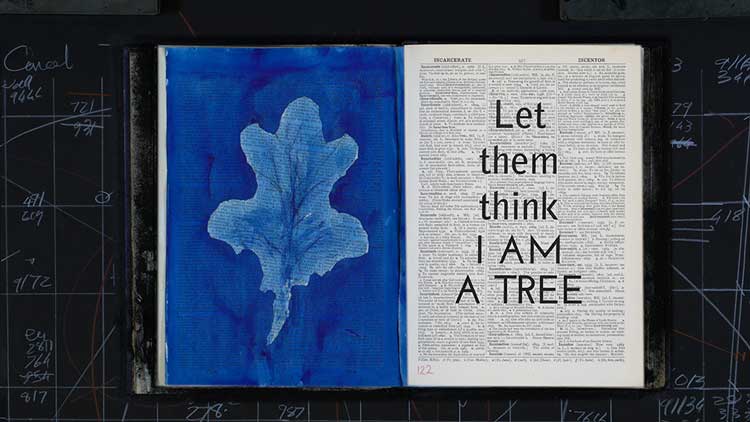

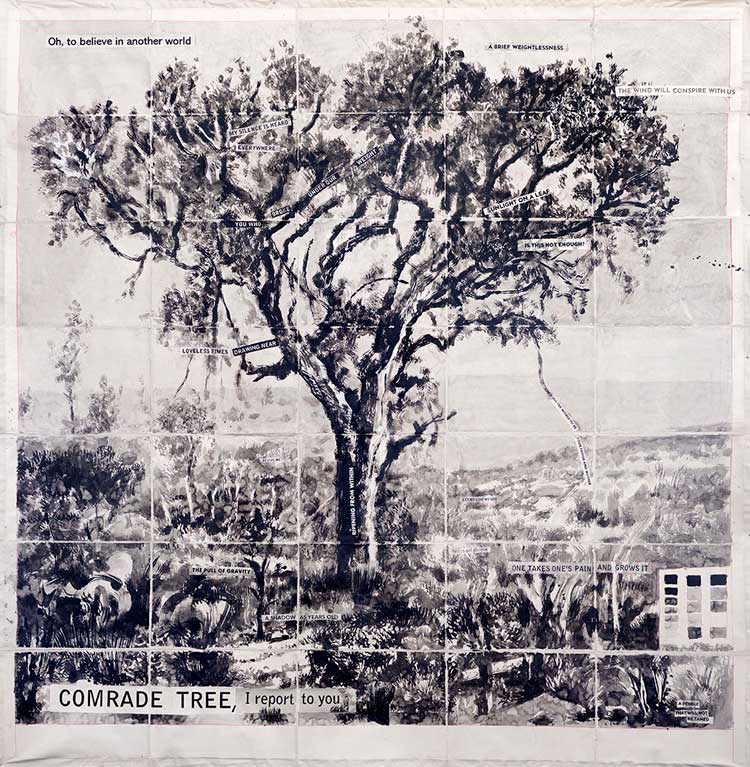

Kentridge’s foray into opera results in tremendous work too. In one sense, we might say it was inevitable for someone with such a theatrical background. Working with composers, set designers and producers, Kentridge brought together an opera, Waiting for the Sibyl, based on the myth of the Cumaean Sibyl. Here, in this exhibition space, Kentridge has worked with the set designer Sabine Theunissen to create the setting for the short film Sibyl. Although this relates to the original chamber opera, it is a separate work and is shown with props, costumes and puppets. In Kentridge’s hands, the myth is transposed into a 20th-century office setting, raising questions of state bureaucracy and control under apartheid. The stage setting and dramatic lighting in this gallery space adds immeasurably to the impact of Sybil. Outside the entrance to the space, Kentridge’s large drawings of trees come together in a grove of sorts. Legend has it that questions about the future were written on leaves for the Cumaean Sibyl to answer, so the juxtaposition of the trees and the film is entirely apposite and, perhaps, a prompt for viewers to ask their own questions.

[image8]

Other large-scale drawings of flowers in a nearby gallery space have a much more personal presence. The context for these is that they have emerged over several years from Kentridge’s domestic setting at home where flowers are sometimes displayed, as they are in many homes. He adds brief quotations to the drawings, much in the fashion of the Rubrics works displayed in another gallery. The quotations are taken from philosophical and medical texts that advocate the health benefits of certain plants. However, through their association to the Rubrics, they also allude to the Chinese Mao-era sayings encouraging citizens to make sacrifices for the good of the nation. As personal as they are, these drawings are so large as to be overwhelming. A display of flowers in someone’s home may be a personal and decorative image, but Kentridge’s images of flowers overpower. Their scale perhaps acts as a reminder, if it were needed, that the personal is political and everyone is implicated somehow in the social and political actions of state. Still, it is Kentridge’s Soho films and their hugely inventive curatorial treatment at the Royal Academy that really swept me off my feet and left me walking home with stop-frame images flashing in my mind’s eye and wondering about man’s inhumanity to man.

.jpg)

.jpg)