Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, c1955 St Ives. © Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust.

Hatton Gallery, Newcastle

11 February – 20 May 2023

by BETH WILLIAMSON

In the same week that the Whitechapel Gallery in London opened its exhibition Action, Gesture, Paint to celebrate the work of about 80 overlooked female artists and global abstract art, the Hatton Gallery in Newcastle launched its 2023 season with an exhibition focused on a single, and arguably overlooked, female artist, the Scottish painter Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912-2004), and her journey from figuration to abstraction in her work. With about 70 paintings and drawings dating from 1935 to 1972, this exhibition provides a real opportunity to look closely and think through the artist’s development before, during and after her years in St Ives as part of the eponymous St Ives School alongside Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth and Naum Gabo.

All four gallery spaces at the Hatton are filled with the work and the spirit of Barns-Graham. As a young woman she was determined to become an artist despite the disapproval of her father, and that determination never wavered, even when illness, personal crisis and, at times, lack of professional recognition, must have shaken her confidence. Still, there is little evidence of that in her self-assured and exacting approach to painting.

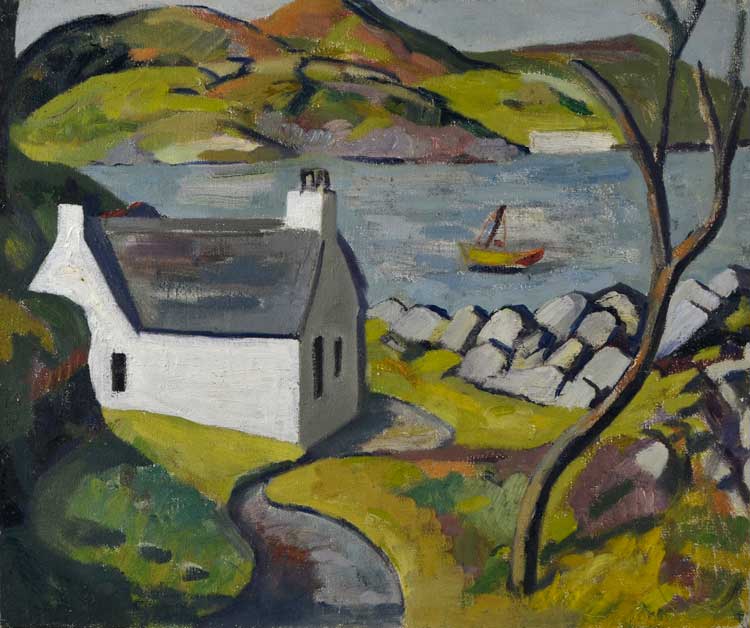

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, White Cottage, Carbeth, 1938. Oil on canvas, 41 x 51 cm. © Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust.

While the exhibition is loosely chronological, Barns-Graham did not follow a straightforward path and that is acknowledged here with the inclusion of one gallery titled Seeing Red, dedicated to her use of the colour red – entirely apposite for a painter who, because of her synaesthesia, experienced colour differently from most people. But the exhibition begins with early work, including three from the years before she moved to Cornwall in 1940. More than anything, these pre-1940s works – The Road (c1935), White Cottage (c1935) and The Episcopal Church, Aviemore (1938) – demonstrate her ability, even at this early stage, to look at ordinary scenes afresh, turning to the ideas of the post-impressionists to represent such scenes with evidently vigorous brush strokes as well as areas of flat colour.

Barns-Graham was 28 years old when she moved to Cornwall and already thinking about how to develop her practice. Once in St Ives, she was exposed to new ideas and approaches to painting through her exchanges with other artists and her renderings of landscapes and harbour scenes quickly show how her thinking about the nature of painting itself was as important to her as the scenes being painted. Over the course of the 1940s we see how her treatment of forms shifts as she seems to become less concerned with the particular scene and more interested in the manipulation of those forms. We also see the influence of her friend Gabo as she uses constructivist ideas of geometry to create space and volume in a two-dimensional painting such as Glacier Chasm (1951).

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, Glacier Chasm, 1951. Oil on canvas, 76.20 x 91.50 cm. © Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust.

Barns-Graham’s exploration of the Grindelwald Glacier in Switzerland, which she visited in 1949, and her developing visions of the frozen scenes she observed there were to have a huge impact on her and sparked a turning point in her career. This is the focus of the second room in this exhibition and her progression towards a more abstract visual language throughout the 1950s is clearly evident in examples from her Glacier Series and Rock Form Series. The beauty of this room is that not only do we see paintings, but also her drawings and works in gouache which reveal her geometric and spatial explorations of the layering and structure of the glacial ice, visible through its transparent surfaces. From its sculptural crevices to the movement and light of its glistening facias, from its massive solidity to its inner luminosity, the glacier became an instructive landscape for Barns-Graham, what she called “a total experience”.

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, Ice Cavern, 1951. Oil on canvas, 60 x 99 cm. London Borough of Camden. © Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust.

She approached her subject in figurative and non-figurative ways, each being separate but related modes of inquiry that enabled her to gain a wider and more varied understanding of its faces, spaces and refracted and reflected light. We might say that it is in the slippage between these two modes of inquiry that Barns-Graham truly conveys her understanding to the beholder. At this point her treatment of her glacier subject is not entirely freed from representation (that would come later), but her trajectory to abstraction is clear enough. Other works in this room such as Passing Forms 1959 (1959) or Composition (Sea) (1954) move further towards abstraction.

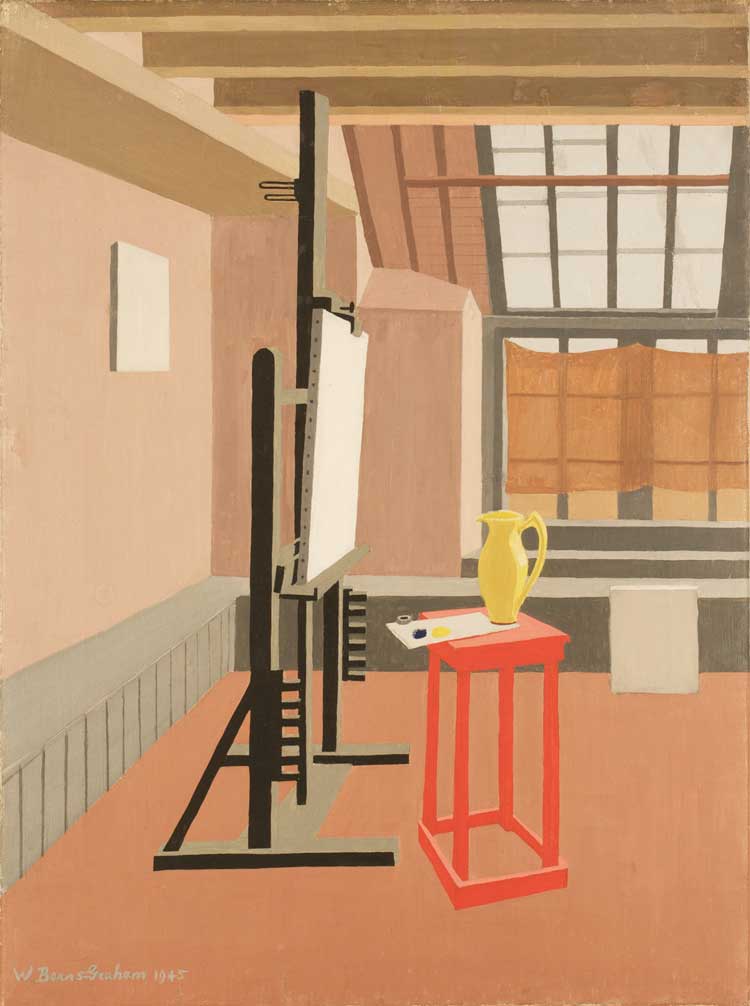

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, Studio Interior (Red Stool, Studio), 1945. Oil on canvas, 60 x 45.6 cm. © Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust.

An artist’s approach to making does not necessarily, or even usually, develop in straight lines, something we are reminded of in the third room of this exhibition. Seeing Red is a healthy riposte to strictly chronological approaches and cuts across Barns-Graham’s career using the colour red in all its variety as its theme. It begins with the entrancing Studio Interior (Red Stool, Studio) from 1945. On another wall the painting Red Landscape (1954) is a rare example of her Italian landscape paintings. Three russet red, almost copper-coloured, drawings in combinations of pencil, tempera and gouache, and made in the Italian countryside between 1953 and 1955, use similar line and form to the Glacier Series. Yet the use of colour could not be more different, so demonstrating the importance of particular surroundings and environments. The vitrine full of Barns-Graham’s paints, chalks, brushes and preparatory works, all in red, is an absolute joy to behold and a prompt to consider the artist’s handling of materials, the daily experimentation needed to discover the right colour, texture and finish needed.

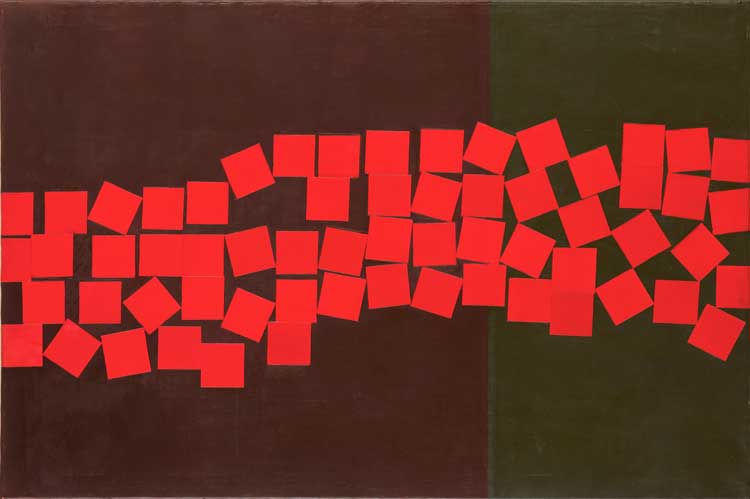

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, Pilgrimage, 1967. Oil on canvas, 101 x 152 cm. © Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust.

The final room in this exhibition largely covers work from the 1960s. Its title, Squaring the Circle, gestures to the purer, more geometric nature of Barns-Graham’s abstraction at this time. It includes paintings that feature a square motif, part of a group of works known as Things of a Kind in Order and Disorder. It also includes work which, in one respect or another, explore her interest in spirituality. Assembly of Nine (1964) is a work that straddles both these groups. Nine is a sacred number in the Bahá’í faith where each sacred assembly has nine elected members. Other paintings that relate to spiritual explorations include Pilgrimage (1967) and Untitled 36/67 (Meditation Series) of 1967 and there is an intensity about the latter work that engenders introspection.

Abstraction does not mean lack of feeling. One of the most joyful works in this show is Bird Song (1966), a simple composition of squares in differing shades of yellow from buttermilk to lemon, from cadmium to canary, from dandelion to honeycomb, it is a pure seam of sensation. The latest work in the show, Burnt Orange Discs on White No 1 (1972), acts both as a summing up of the artist’s explorations in colour, movement and form thus far, and as a pointer to her continued experiments in the years that followed. There is no doubt that this exhibition covers a lot of ground. It is clear about its narrative – the path to abstraction – but rather than tell that story in a didactic fashion, it shows visitors through its presentation of the work itself, allowing them to find their own understanding, just as Barns-Graham did. It sets the scene for what came next and another exhibition addressing continued evolution of Barns-Graham’s career from about 1970 onwards is surely to be much anticipated.