by YASMEEN M SIDDIQUI

Wangechi Mutu (b1972, Nairobi, Kenya) works to address the idea of human representation. Her figurative practice reshapes value systems to obscure or clarify others’ views. In her collage paintings, sculptures, films and performance rituals, she uses ink, soil, ash, bronze, driftwood, horn, pigments, wine and hair.

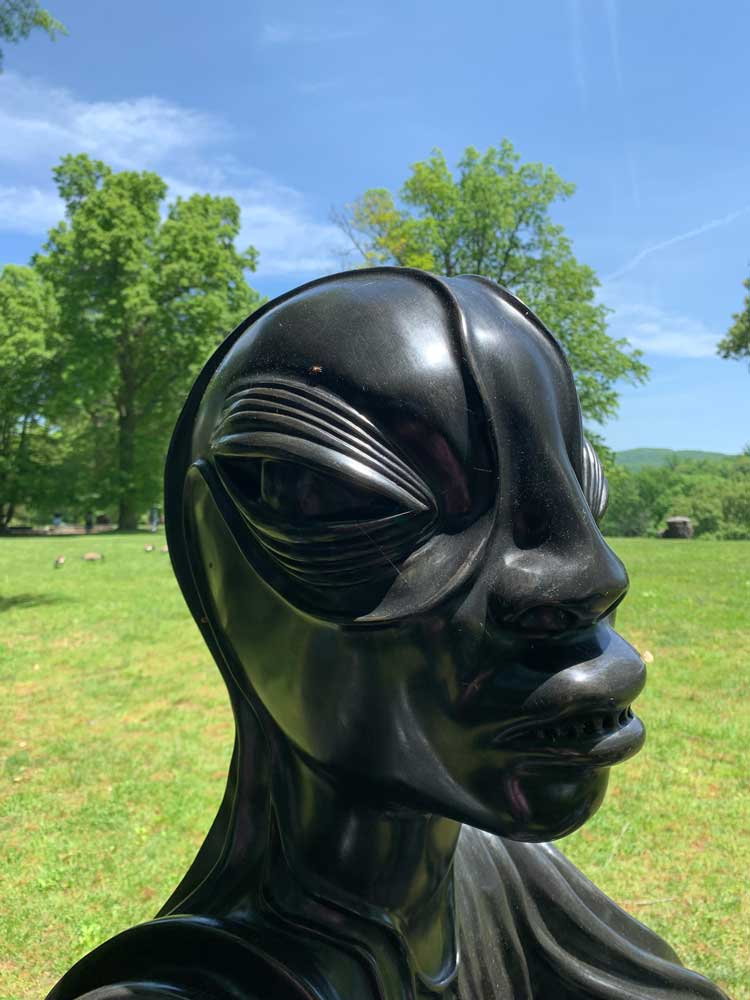

Taken out of the gallery, Mutu’s hybrid sentinels and animistic cyborgs reign over avenues and across bucolic art-strewn fields. Light as they are heavy, sure-footed in bronze, in their forms, I recognise the future. Her work divorces bodies from technology and its machines to remaster their given roles and their given names. The forms imply a quest for identities tethered to physical, material, real and earthly conditions.

It is usual to find a caryatid holding up an entablature or a facade flanking a grand entrance, with the building resting lightly on their heads, held up effortlessly by hands. The caryatids have, until now, submitted to the will of power. Mutu’s do not; hers embody power. In 2019, spanning the front steps and entrance to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Mutu’s four caryatids, titled The NewOnes, Will Free Us, looked on to the street from niches carved into the museum facade, a symbol of a long-lived empire. They harnessed the sun and demanded we reckon with the gendered colonial logic that continues to dictate how our names ring in the ears of others.

[image2]

This year, north of the city, on hills abutting buildings are works equally heavy and light, grounded, tethered to earth, an earthscape of clay masked by short-clipped green lawns. The site weds the past, present and future. Fraudulent treaties expelled the Munsee; the Dutch followed by the English claimed this viewshed, eventually handing over the landscape to the state to birth Storm King Art Center, formerly the Vermont Hatch mansion, built in 1935 for a New York City lawyer. A complex layering that weaves a container, a context that builds resonance within this show brings forward the ways in which nature anchors Mutu’s practice and, most importantly, the ways in which nature performs as a root concept in the stories we tell ourselves as humanity plots and perverts how to be and how to propagate. It shows how to organise and mythologise social order.

Family trees

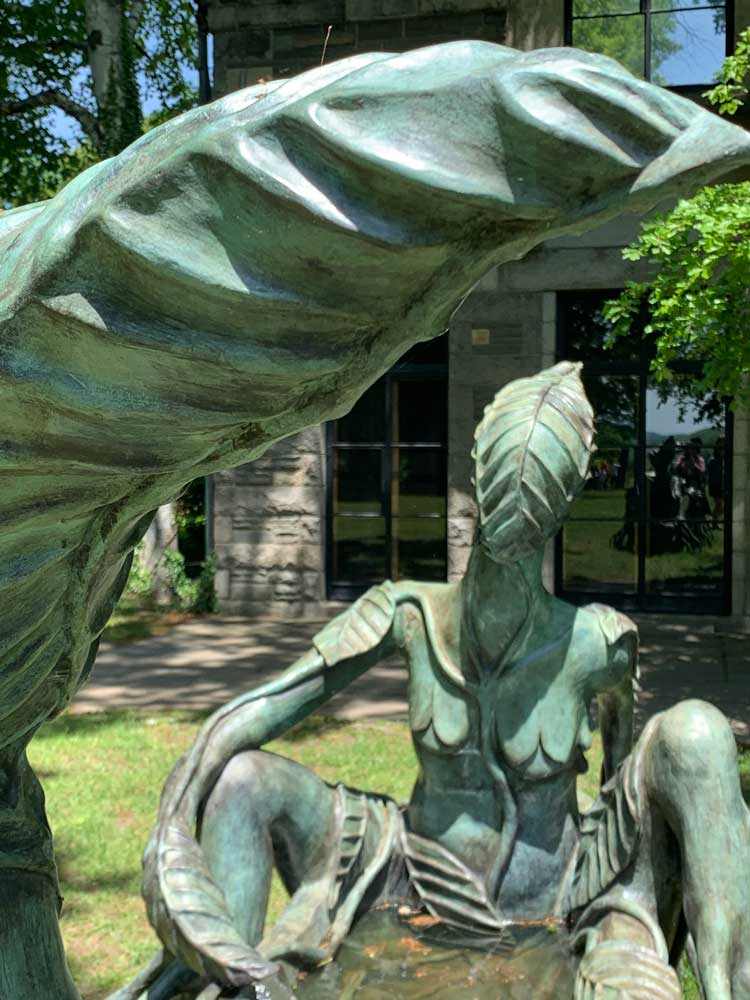

Mutu’s caryatids perched along the Met’s entrance wall were among the efforts of her and others to reposition the treatment of bodies within the field of visual arts, a realm configured over time and place. The statues were seated, watching the passersby below; they were guardians three times larger than their human masters. They operated differently from the array of bronze sculptures planted at the Storm King Art Center in the Hudson Valley through another season, into autumn: a series of cast baskets holding snakes, braids of hair, tortoise shells, and a pair straddling a canoe-shaped fountain, branched legs drifting to ground, rooting. They are all on view in the specifically charged condition of now, in ways brought to bear on the word “woman” as it is leveraged and catalysed among diverse camps of feminists and their naysayers.

A modern empire sets this stage. Centuries hold the work of Mutu, and as such inflect ranges of place and sensibility on her women, her world order. Familial orders are a constant reference and refrain in culture, a framework for excavation by the likes of many. For today, I draw on intuition while locating a mix of ideas and impressions taken from transdisciplinary futurist painter, poet and performer Valentine de Saint-Point (1875-1953) to the early-19th-century writings of a young Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley and those of a 20th-century sage, Octavia Butler, and to the fetishist experiments of Orlan. Their influence echoes in the gestures and forms Mutu creates.

My Cave

I Pray

I Cave

Sand clouds

Butterfly, bird, clouds

Earth

This refrain in Mutu’s short film My Cave Call (2021) beats in tandem with the delivery of phrasing across the artwork’s undulating soundscape, a repetition that taps away to redeposit traumas listed and chanted in the film, extracting, not erasing, colonial aggression and violence from our daily responses and thoughts like a prayer. Read and recited are images of: bodies scratched, whipped. They bound her legs, cut her ribs, gouged at her yes, stitching her mouth shut, put metal worms in her back, glass under her feet.

[image8]

My Cave Call begins in magic. A glittering protected glen, under tree cover, strewn with butterflies. Here she reclines book at her side. This scene remains first in memory. The previous scene, coloured to evoke travel posters from the 1970s, shows the mountains, rolling farmland and ranches of Laikipia in Kenya. She places the primordial before the romantic. Gateways to the mystical, where ritual and prayer take place in the Suswa caves in Kenya’s Rift Valley, to form the film’s centre. There is the migration through sections that are marked by hue: vaguely anthropological inflected sepia tones to a kaleidoscope-twinkling dreamscape, surfaced to refract light, and then into the cave caught in the grey tones of prayer. In 12 or so minutes, there begins the trip, and method for remapping pasts and muting the legacies of colonisation of women’s bodies, to quiet the violence imposed over centuries.

She descends to the cave floor, arms extended through costume. Sleeves longer than arms, hands and fingers form ribbons that move as if belonging to a dervish. This form, this costuming, appears in Mutu’s earlier watercolour and collage works. Recurring forms, a symbology tied to a body of work that, over time, tells of an artist who is shifting from keen observer and chronicler of masochisms and hegemonies towards working with the ways of a healer.

Characters listed in this film typify Mutu’s long record of contemplating the past and its power when reified and held front and centre within consciousness and discourse. Mutu tracks the future, the past and the present. Poetic recitations evoke historic, mystical figures and their protectors. The soldier birds called Giky. Orkoiyot, a seer, a 19th-century prophet with the gift of grace, speed and momentum, held dual function as chief spiritual and military leader of the Nandi people. Another figure referenced in the telling is Cege was Kibiru, a prophet of the Kikuyu. Their names sound across the film, to form a story, reminding us of oral tradition. They are part of the landscapes and cave settings through which a statuesque female figure moves. Each figure, described or depicted, spliced in this film effects distance between the place and power of masculinity and its requisite violence.

Mutu readily enters unstable histories to remaster them from the inside out. This year, Carnegie Hall in New York produced a citywide series of Afrofuturist performances. One of the key organisers was the film-maker, dancer and author of Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture, Ytasha L Womack. She argues for this cultural movement as a formulation to better explain the feelings and sense of otherness. Contributing to the legacy and writing of Greg Tate about science fiction, music and the power of expression to envision through creation and manifesting beauty worthy futures. Scholars who have written about Mutu.

The French artist Orlan, who came to notice in the 1970s and reached notoriety in the 90s for the plastic surgery to transform her face, strikes me as radically useful when thinking about Mutu’s collages, that with paper tell of violence, misogyny and the making and impacts of taxonomies. Orlan, with her body, decries the categories of arts histories, the valuation of womanhood, using the tools of science to twist and contort her flesh. The extremities of facial contortion and adjustment we see in photo documentation of Orlan’s surgeries indicate how her aesthetic goals were brought to life in flesh. When Orlan breaks the rhythm of features and forms that are expected, when she alludes through resculpting her face to iconic female subjects of art history or faces excavated on her anthropologically oriented trips through the Americas or Africa, she cuts the cord between her and her birth family and weaves a connection to broader swathes of history. Her face is used to disrupt and remap her identity. How else could she unravel the ways our stories manifest? Mutu takes us there. Stepping hard on to symbolic systems, the family tree, and creation, conjuring origin stories to make sense of the pang and antics of power in our daily lives.

[image5]

These are two very different encounters with colonial pasts. Orlan mirrors the extractions and incisions that French colonialism wields on humanity. Mutu creates in order to propose futures through setting the past, like setting a bone, setting it right. One reflects, the other responds. These are two aspects of a long story; two sides of a coin.

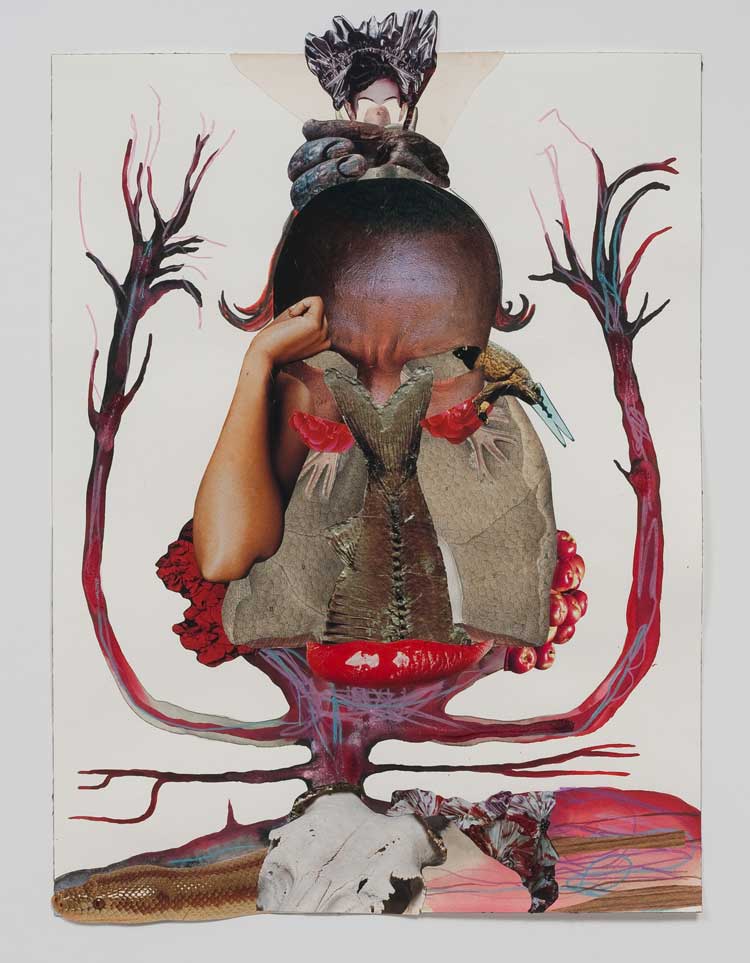

In 2013, at the Nasher, an expansive exhibition of Mutu’s sculptures, film, collage and painting allowed for a close reading of her cosmology and the need for mythologies. Front of mind is the subject of amputation, why is it used at this moment or that. What is grafted? What is conceived? Is the body in question a result of grafting and amputation followed by figuration or is it following an internal logic having emerged just as it appears with incongruities, textural clashes and material mashups: metal up against tendons strewn across vegetation. Family Tree includes 13 figures, each portrayed alone in what seems an entire universe built of disconnected others were it not for the lines tying two parents, their three children, the two spouses of their children, and six grandchildren. Mutu has drawn the cosmos according to a female-dominated creation mythology.

[image4]

At the top of this familial hierarchy are Original Sky and Original Land. Each convey a suggested dominant gender, Original Sky with attributes usually assigned as feminine – wideset large eyes, wispy arms, long fingers gracefully anchoring body in space, holding their posture is a heavy bejewelled hand disproportionally large, muscled, thick, pinning the figure down. Original Sky is beholden to someone. Original Land is double-headed, or triple-headed if you include the pelican with carved-out eye. Mounting a mosaic landscape accented by palm fronds and fabrics, the profile of a Scotsman, indicated by clothing, formal regalia, lies beneath and pushes upwards and outwards through a woman’s head. He occupies her, a quarter of her face is stripped back to reveal him. The bird clutches a branch. Behind them are clouds and blue skies. Each figure is built out of body parts, organs, vegetation, machines, gun parts, scientific drawings, fabrics, magazine cut-outs. Out of the 13 portraits, eyes are usually turned away, exceptions, such as Blue Lips and Guts Smile stand out. The Prodigal Sun Daughter with an intrinsic beauty stands alone: no spouse, no children, her autonomy expressed through long lashes and clean markings in blue and red connecting from forehead to throat. She and Original Land are related with the symbol of a bird. This is a story of the cosmos, an origin story, a creation myth that depends on history and its futures.

Botany

A genealogical map relating the paintings presses the point, so we don’t miss it. Mutu’s work is made up of propositions to loosen our minds so they can rethink impressions of what it is that we are. In 2007, she shows a body of work titled Yo.n.I at her London gallery, Victoria Miro. Splicing human and plant bodies, she forces us to think in a direct way about the uses of biological science and the roles of scientists in violent histories. Reproduction, central to genealogical charting and a subject of Yo.n.I, begins in a study of plants from which she generates fertility myths, visualised in the sex organs of tropical flowers and the forms that the fallopian tubes and wombs assume, to steer her in creating a symbology for conception, growth, birth, renewal. This research leads to the scientist best known for developing the classification system for naming plants and lesser known for his role in the pseudo-science of physiognomy, which he based on racially charged terminology. More than half a century before Mary Shelley created her monster and its maker, the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707-78) systematised plant naming, where genus and species name are expressed in Latin. He extended his thinking to us by dividing humanity into four subspecies, inspiring generations of eugenicists. His categories will, sadly, not surprise you, for their persistence. He, naturally, is a member of Homo Europaeus, while the lowest, that he classifies as “crafty, slothful, and careless” are Homo Africanus. Contentious are the bonds of science to the dreams of utopians. This makes me wary of categories for the sinister ideas that lie beneath many re-imaginings, including terms we use with confidence and hope now as we expand terms used to label the genders.

[image3]

Shelley at a young age unravels the family unit, working through the pangs of British and French imperialism and exploitation at home. She drills down into the cravings of science to master creation in heroic form. Her scientist, Frankenstein, pieces together parts of creatures and mechanical elements to build an early, crude cyborg. Her integrating a cyborg into an existing social unit, in this instance a family story, unravels over the course of three volumes. The scientist’s invention, the monster, quells rage and frustration through revenge: a cycle of violence profound and unrelenting. Artists find ways to break away to envision new societies and structures potent enough to liberate individuals and their communities. Using direct reference, Orlan recalls James Whale’s film The Bride of Frankenstein in her move to express an identity devoid of anchor. These ideas connected to liberation and reinvention figure valiantly in De Saint-Point’s world view and are amplified through her widely circulated, often recited, early 20th-century Manifesto of the Futurist Woman. Shelley’s constellation of character names charts connections between friends, family and foes, bonds magnified with each of the monster’s kills. Where one such as Orlan might quote Shelley’s characters, Mutu seeks understanding in the links among botany and the human biological sciences to reimagine origin stories.

[image10]

Fortified behind heavy stone walls, in the Vermont Hatch Mansion, are galleries containing delicate sculptures made of water-soluble materials – earth, clay, wine and shell – and Mutu’s films. There is a parade of animal forms, eyes out of shells, limbs made of twigs, bodies of earth, that march in an infinite circle and hold our gaze with theirs. Niches in stairwells house skulls that dangle from above and protect passages through to view films and examine configurations of earthly elements, objects findable on walks. Of the many entrances to perhaps half a dozen rooms with Mutu’s work installed, one stands apart for its monumental instead of domestic or intimate scale: She Walks (2019).

[image9]

We see her back at first. Details are hard to make out from a distance, shadows more subtle than in the outdoor bronze sculptures, whether the monochromatic surface of Crocodylus (2020) that glistens, or the seeping green and grey patina of In Two Canoe (2022) that is animated by reflections of water pooling in the boat in which the figures sit. The scene is made more dramatic by the dappled light of planted, shaped and pruned specimen trees. Sourwoods and European weeping beech frame Museum Hill and Mutu’s bronzes.

[image6]

[image7]

Trapped inside there is a sentinel; she is of the earth. Her red-soil form reaches statuesque height. The form grounds to the floor. Synthetic hair and paper pulp add texture and allow for a subtle play of light that does not inhibit or restrict the feeling of being in motion. Mutu’s sentinels are not always gendered. One of speculative fiction’s greatest characters is the shapeshifter Anyanwu, Octavia Butler’s counterpoint to Doro in her novel Wild Seed. Anyanwu has only herself and her magic. She does not have a god to pray to. Three hundred years old and seemingly immortal, she marries Doro, a man she cannot escape or outlive. Anyanwu lives for a period as a diminutive muscular man, feeling safer in this body. She, like Doro, can change form. Like Mutu, Anyanwu navigates time and space, acting as a protector of her children.

Iterations of Mutu’s sentinels have been shown in museum exhibitions, for instance at the 2019 Whitney Biennial gallery shows at Yale and at the Victoria Miro. The stance of She Walks is wide and again sure-footed. Powerful legs and winged arms feathered with artificial hair hold this divine feminine form that guards and grounds the show’s interiority. Recurring across Mutu’s collages, withinFamily Tree, and on her sentinels is the placement of a bird on heads. Combining human and animal parts into singular beings is ancient. The sentinels include discrete elements that suggest the power of birds. Fusing animal and human occurs often in bronze: Crocodylus is woman and crocodile. MamaRay is woman and manta ray.

These visual experiments, collaged extractions from papers, magazine coupled with painting and the grafting of forms realised in metals or soils animates an interpretation of shapeshifting quite different from the approach that Butler’s Doro takes. He assumes forms and dons new skins through quick kills. He is ancient and immortal, and driven by his desire to contend with what he feels he cannot change: the existence of the slave trade. His power and his impotence coexist. Like the artist Orlan, they cannot stop systems, so they express moments of control over them. Doro and Orlan play with the logic of eugenics.

When Orlan performs one of her seminal transfigurations, she commands the surgeon to cut away and rebuild her face, mutating orifices that connect her to biological parents. Mutating her nose, central to her face, she makes herself unrecognisable, even repugnant, ideation by force of knife. She tests her parents’ attachment. Looking to her face, we ask where she is. Orlan theorises her body as readymade to be altered, and with its alteration, through experimentation with hybrid forms, she tests what the cut can achieve. Can it undermine her DNA to generate different skins? Will these surgical adjustments be replicated when skin regenerates? If the artist’s vision and surgeon’s cut are replicated through natural process, can we find these changes in the subject’s DNA? These literal slices into life are the concepts Mutu forms as hybrid machine and organisms. They are connected in an unabashed treatment of popular culture, violence, rape, sexuality, exploitation, war and memory, mutilations and the scarring of surfaces to characterise all that is grotesque and baroque. They perform ideas about masquerade that impinge on and tinge societal norms. We are asked to think about the augmented body with its capacity to remap the brain and question where and who is the original body, what is sublimated and what material is left, and whether it will surface.

Fantastical bodies

Back flat to the ground, pincers clasp pink toes. Knees bent, splayed, legs shoot straight from the hip. A perceptible line marked by the shadow tracks from between knees, counter-intuitively downwards from the crotch exiting to earth via the head’s crown. This photo taken in 1913 during De Saint-Point’s Poème d’Atmosphère performance describes physical prowess: flexed arm muscles, leg muscles relaxed to submit to the will of the form. There is no space between body and ground. Her arms span outwards straight from shoulder to elbow. Elbow skin presses against the ground, wrinkling on contact. The brocaded neckline and stitched headdress with opaque veil trace nose and mouth falling deeper, pulled in by her breath. Her choice is to be anonymous through choreography and costuming.

During this performance, De Saint-Point is a year shy of abandoning the futurists in response to their growing lust for violence and racism, a development she finds uncomfortable. Her story is at its midpoint. She will have half a life left to fully embody the persona she crafts through the name she chooses.

Deeply psychological and political, De Saint-Point upends her classical education, which she felt generated a version of womanhood trapped in a state of perpetual emergence, a reactionary state and response to maleness at the expense of intrinsic and felt interpretations of experience. Through performance, she tests the limits of fragmenting body and voice and completes the weekly programme with a lecture on the theme of women in literature between 1910 and 1911. Like Orlan, each of De Saint-Point’s performances is coupled with a contextualising lecture to ensure audiences grasp the correct version of events, leaving little room for misunderstanding their charged, radical ideologies that we can track later to the subsequent works of surrealists who similarly ground themselves in psychologically rich responses to politically fraught images and imaginings.

It is striking to me the impact many female artists and writers since Shelly have made on the conception on women’s bodies, cyborgs and monsters. A thread that weaves many together are thoughts about the limits and possibility of reproduction. Shelley wrote Frankenstein in her teens. She had four babies; three died. That experience with bodies, their formation and decomposition, their fragility simmered in her study of the outsider and the incorrigibility of science. The rooted anxiety of the possibility of pregnancy, whether through rape or consensual sex, persists in many young women through the early phases of adolescents. Interlacing lust, desire, anxiety and survival through this period into adulthood proffers different reactions and responses that I continue to explore, poking around in the works of others, splicing and interconnecting the work of Mutu and Orlan to suss out insights embodied in their cyborgs.

Off-putting or contentious, contemporary artist Orlan harnesses face and features through the surgical reconfiguration of her own face to propose ways to shelve social norms relentlessly tied to religion and prevailing psychoanalytic interpretations of womanhood and gender. Her face is a surface, that over the course of three years and nine surgeries, behaves as a canvas on which to quote and embed familiar references, changing her facial topography and her origin story.

Rooted perhaps in the arguments embedded in Shelley’s young writing, Mutu, Orlan, Butler and De Saint-Point ask through their creatures: “Why did you create me? And why did you create me this way? Why do I assume this form? Who are you creator? And if you created me, why?”

De Saint Point’s Manifesto of the Futurist Woman circulates in 1912 to express new stakes for women with the core idea: “It is absurd to divide humanity into men and women. It is only composed of femininity and masculinity.” She is unapologetic in her description of periods defined as violent, sterile and obsessed with war as masculine. While periods characterised as feminine were tranquil, regressive, backward looking, and always annihilated while fantasising about peace. She blends masculine and feminine traits within each body so as to arrive at equilibrium and virility. She intersects temporal and spatial dimensions to rebuild bodies, to reconstruct woman and, by default, man.

Anti-clerical and working with the idea of electricity that relates organic and mechanical forms are concepts percolating through these artists’ visions for female futures. Whether Shelley’s Safie, De Saint-Point’s Sufis or Greater Syria, Mutu’s sentinels and hybrid bodies, or Orlan’s radical anthropology in all its problematics, they share a need to rewrite classification systems through the visual, the sonic and the literary. They take hammers to family trees and start fresh, aware of the burdens of what persists. They push into view ideas that futurists profess, enacting fundamental separations with pasts, with family orders, with patriarchy and its empire in its myriad forms.

• An exhibition of Wangechi Mutu’s works is at Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, New York, until 7 November 2022.

.jpg)