by David Thompson

(This article was first published in Studio International, Vol 171, No 878, June 1966, pages 232-243.)

British participation at Venice is not usually the subject of much comment at home, particularly before the event. But this year’s selection of Caro, the Cohens, Denny, and Richard Smith seems suddenly to have aroused people’s interest. Featured already in Vogue Magazine, (‘Merchants of Venice?’), trailed by B.B.C. cameras all the way from their studios to the Giardini Pubblici, the five artists have obviously been recognized, even beyond the specialized confines of the art world, as ambassadors of a new ‘image’ to this Biennale. Not since 1952, when the famous ‘manifestation’ at the British Pavilion put postwar British sculpture on the international map, has the British Council deliberately chosen a team so equally balanced, both in age and accomplishment, in order to make a point about British abstract art over and above the individual merits of the artists themselves.

In no way do they, or are they supposed to, represent a movement or a shared aesthetic. But they obviously do, in a sense, link up with one another, represent a shared climate of achievement, and the point that their work makes, particularly to a European audience, is that both painting and sculpture in this country in the mid-1960’s is led by a generation (the most senior of them only 42) which need defer to no one—neither to English tradition itself nor to America—in the originality of what it has to say and the authority with which it says it. London may or may not have become in the last few years as important a creative centre as New York. But the claim is often made, not even in a particularly chauvinistic spirit, that it has done so, and Venice this year is an obvious place to present the evidence for such a claim.

The temptation is to see these five, because of the circumstances in which they are being shown, as too closely linked. There might seem, for instance, to be a certain neatness about having, at one end of the scale, Caro—the sculptor who has more than any other pointed the way for the current trend of sculpture towards painting—and, at the other, Richard Smith, who more than any other is extending painting towards sculpture. Between these extremes lies a whole new concern with illusionistic techniques in the treatment of space which is particularly characteristic of British art at the moment. But without wanting to over-stress affinities within the group, I think it is still worth pointing out one or two ways in which they illustrate certain current preoccupations in this country. Decisive in the development of all five, for example, has been the catalyst of American painting, even if its main relevance now is precisely how far its influence has been superseded.

American painting shook British art out of its provincial habits, gave it a new awareness of scale, and a new confidence in what non-figurative art was all about and what it was capable of. (The 1960’s in Britain have above all been a period when sculpture has stopped feeling a need to make surrealistic references to the human figure and painting has stopped having to refer compulsively to landscape and atmospheric space.) But just as significant as what was learned from American example has been what British art has retained and since developed of its own more European complexity of response. More actually goes on in a British non-figurative painting than in an American one (which is not to put a value-judgement on it—merely to describe a characteristic); and this is not just a question of the kind of multiplication of effects that one finds in either of the Cohens’ paintings, but of the various layers of meaning, reference, and technical ‘reading’ of the work presented by Denny and Smith as much as Caro, all of whom may seem to practise a markedly spare or ‘simple’ idiom.

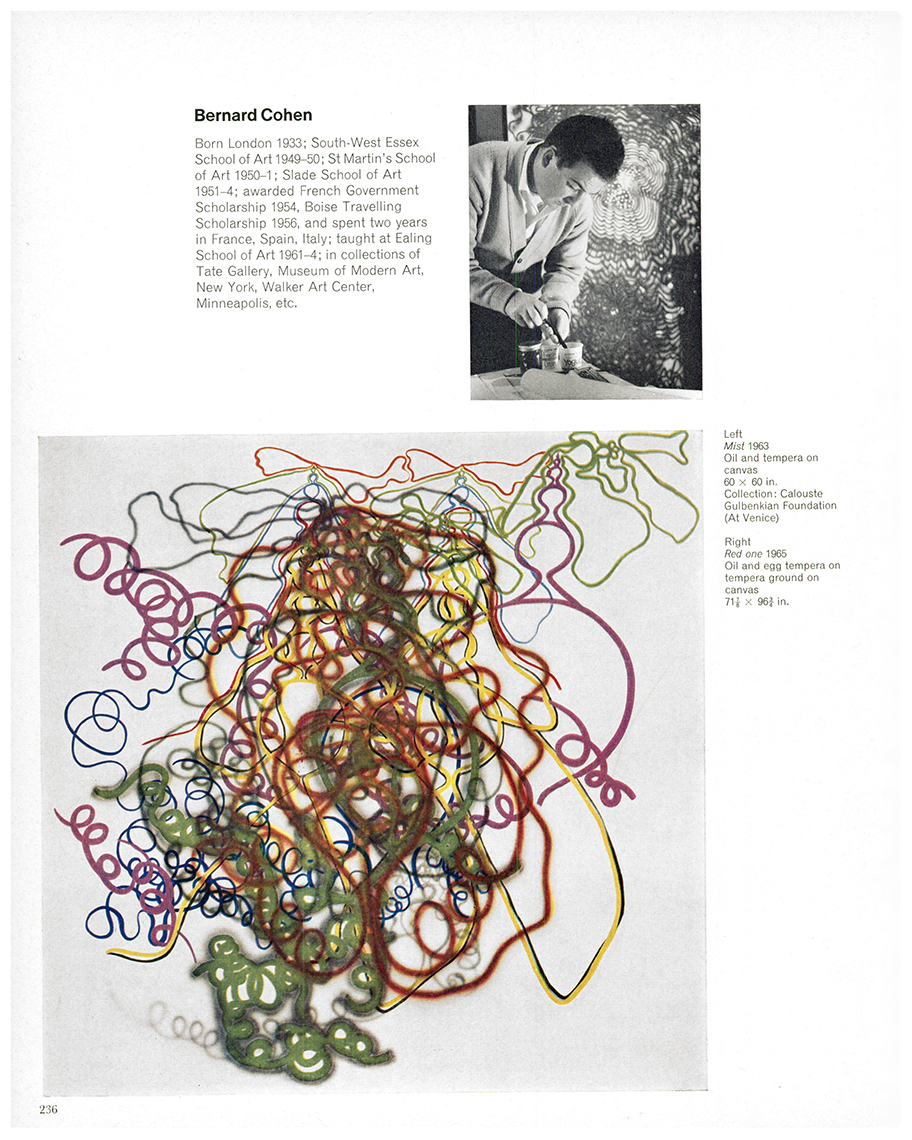

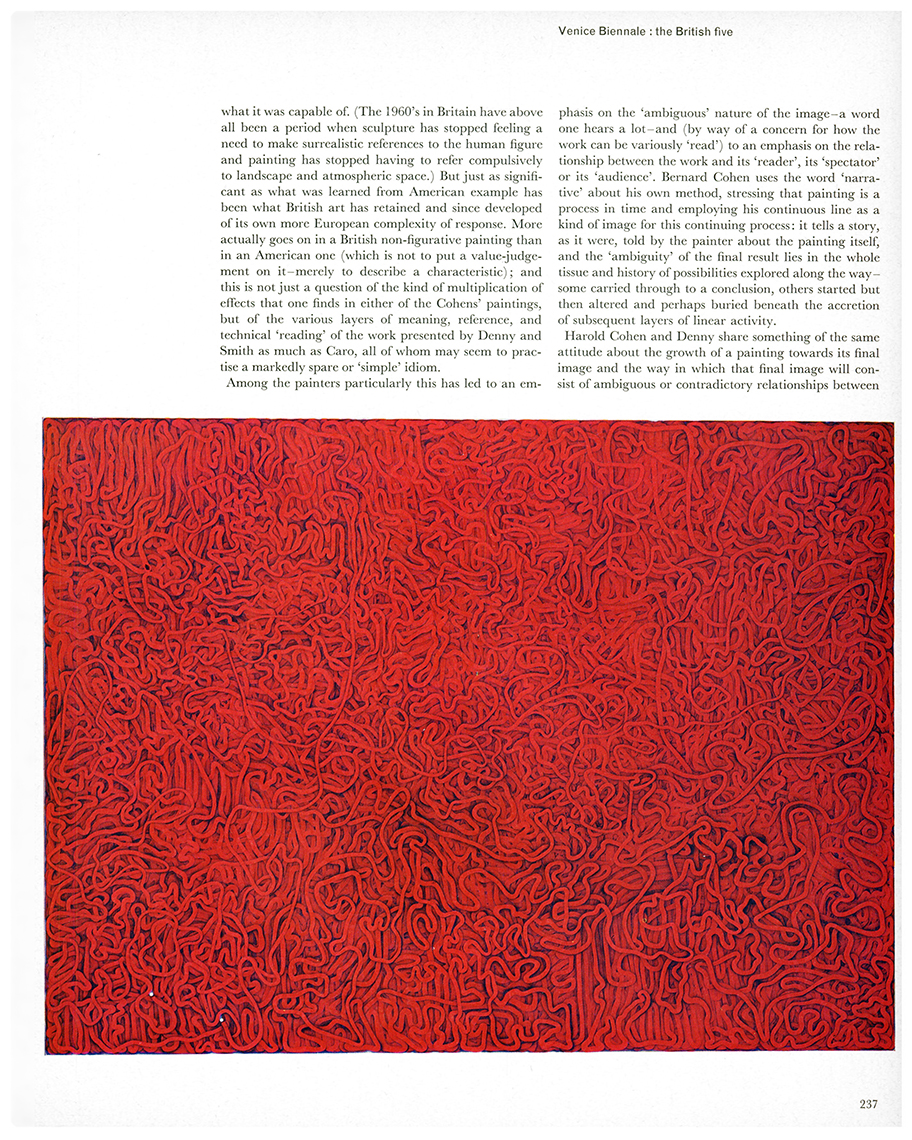

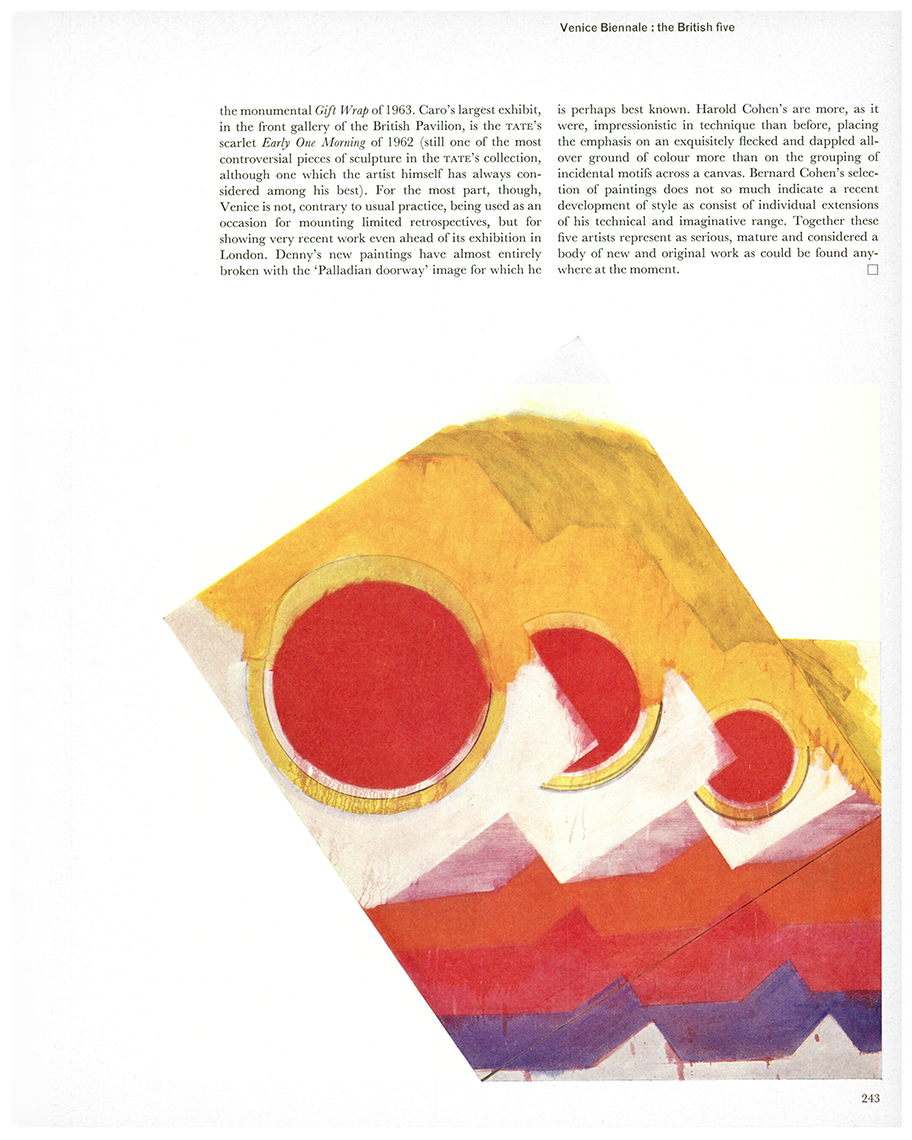

Among the painters particularly this has led to an emphasis on the ‘ambiguous’ nature of the image—a word one hears a lot—and (by way of a concern for how the work can be variously ‘read’) to an emphasis on the relationship between the work and its ‘reader’, its ‘spectator’ or its ‘audience’. Bernard Cohen uses the word ‘narrative’ about his own method, stressing that painting is a process in time and employing his continuous line as a kind of image for this continuing process: it tells a story, as it were, told by the painter about the painting itself, and the ‘ambiguity’ of the final result lies in the whole tissue and history of possibilities explored along the way—some carried through to a conclusion, others started but then altered and perhaps buried beneath the accretion of subsequent layers of linear activity.

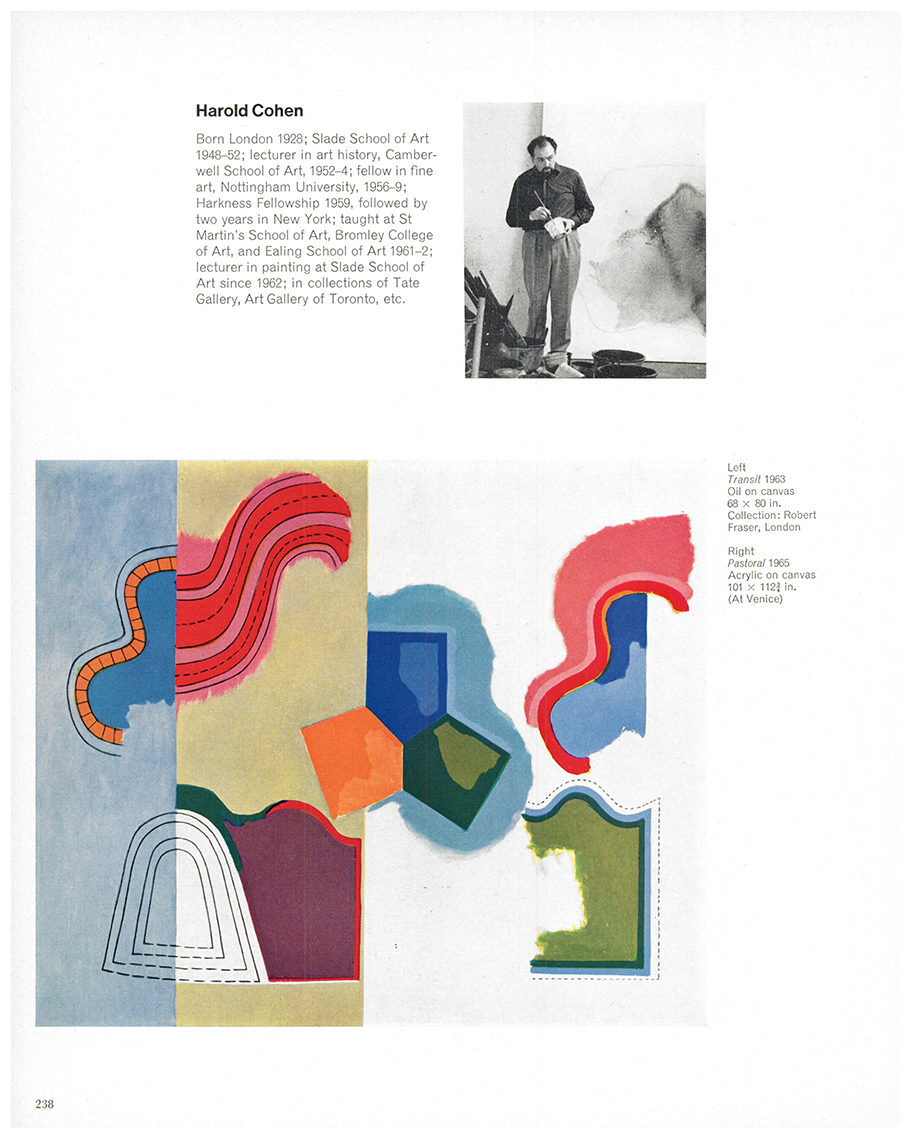

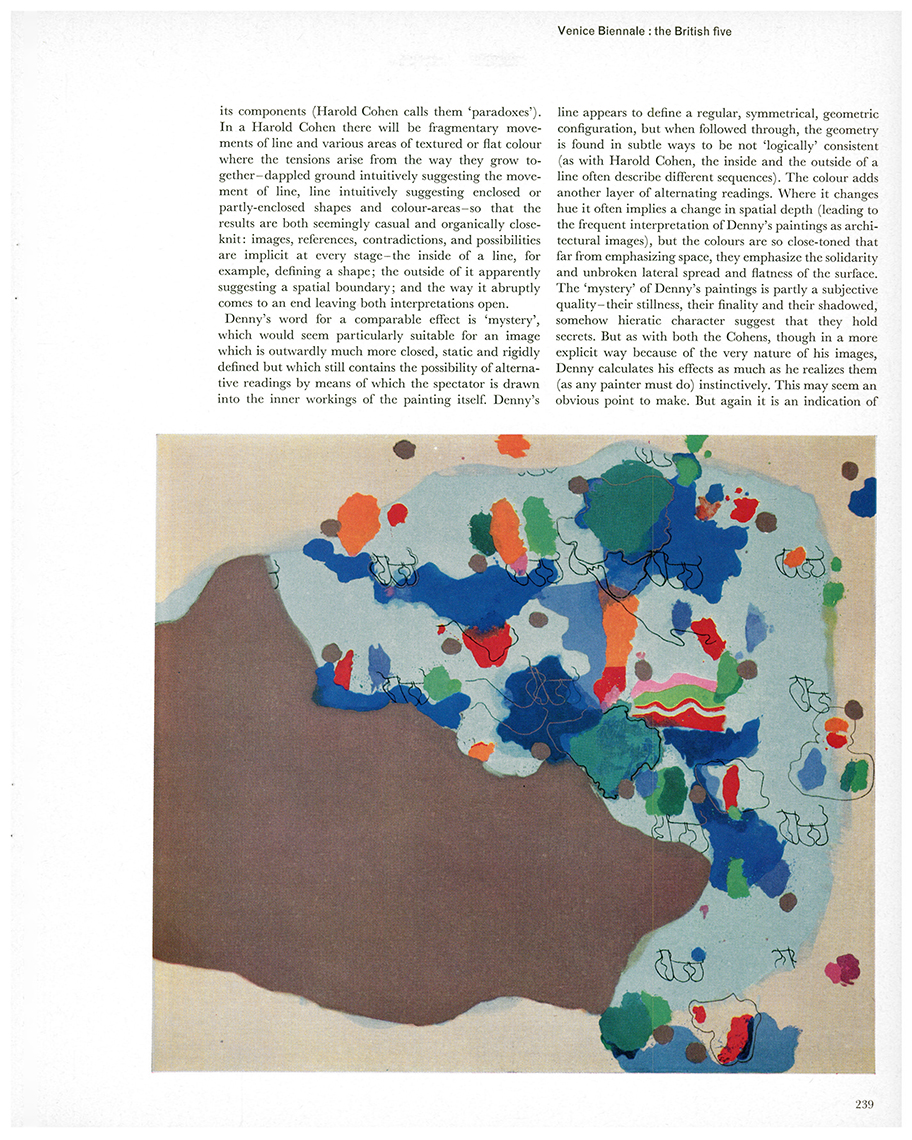

Harold Cohen and Denny share something of the same attitude about the growth of a painting towards its final image and the way in which that final image will consist of ambiguous or contradictory relationships between its components (Harold Cohen calls them ‘paradoxes’). In a Harold Cohen there will be fragmentary movements of line and various areas of textured or flat colour where the tensions arise from the way they grow to-gether—dappled ground intuitively suggesting the movement of line, line intuitively suggesting enclosed or partly-enclosed shapes and colour-areas—so that the results are both seemingly casual and organically close-knit: images, references, contradictions, and possibilities are implicit at every stage—the inside of a line, for example, defining a shape; the outside of it apparently suggesting a spatial boundary; and the way it abruptly comes to an end leaving both interpretations open.

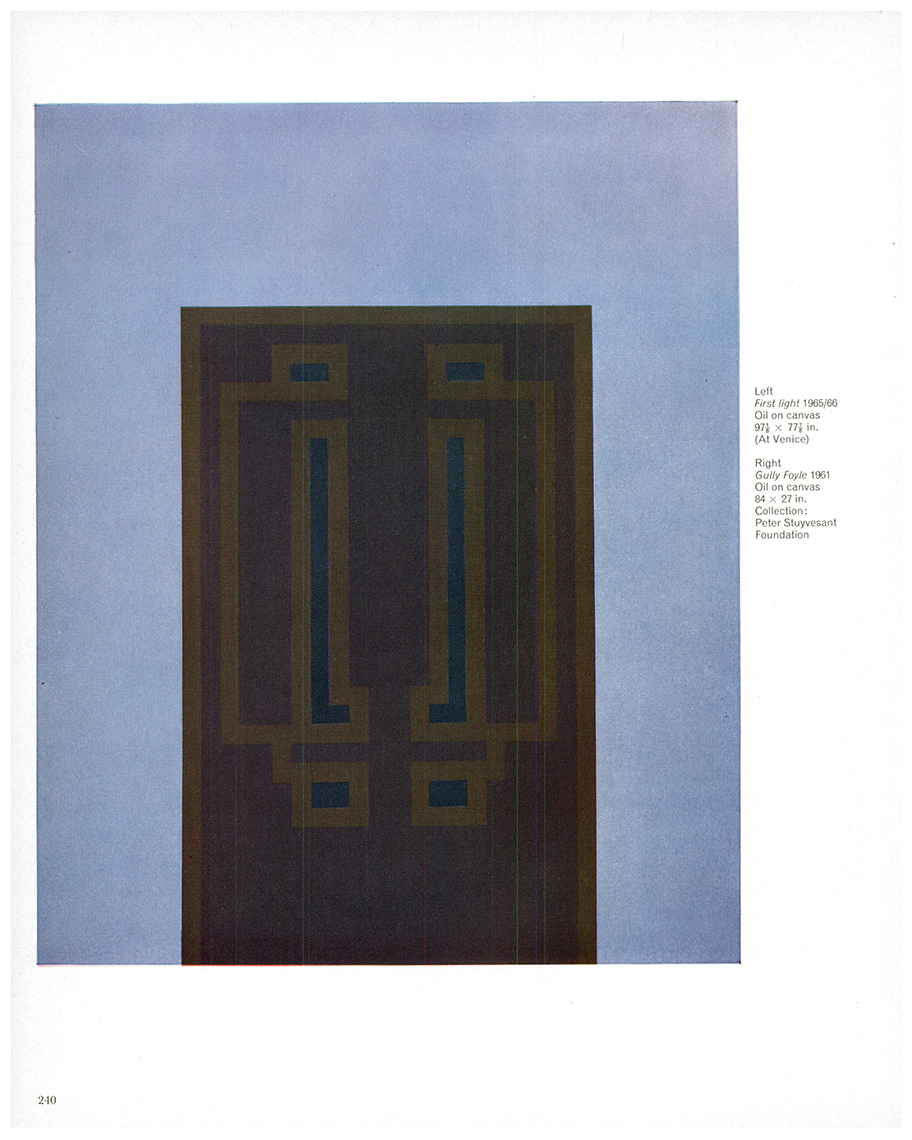

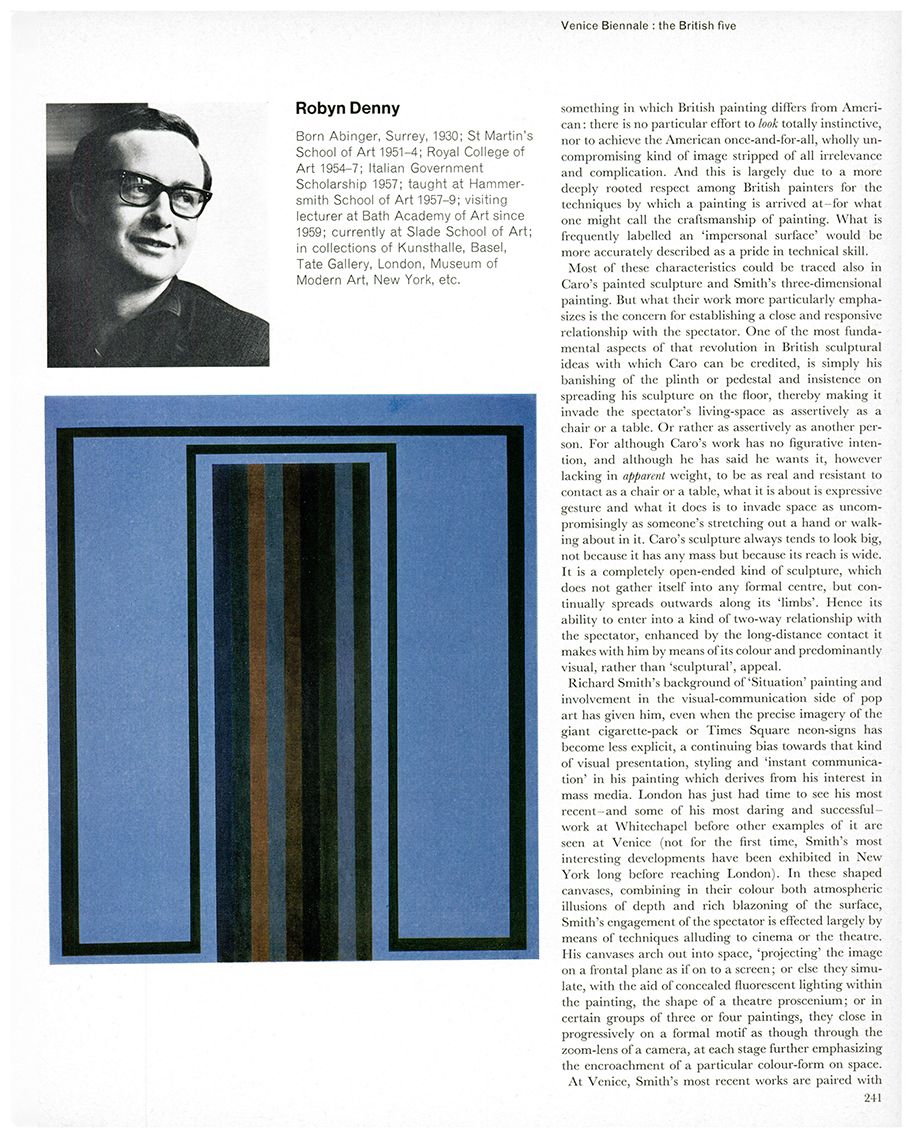

Denny’s word for a comparable effect is ‘mystery’, which would seem particularly suitable for an image which is outwardly much more closed, static and rigidly defined but which still contains the possibility of alternative readings by means of which the spectator is drawn into the inner workings of the painting itself. Denny’s line appears to define a regular, symmetrical, geometric configuration, but when followed through, the geometry is found in subtle ways to be not ‘logically’ consistent (as with Harold Cohen, the inside and the outside of a line often describe different sequences). The colour adds another layer of alternating readings. Where it changes hue it often implies a change in spatial depth (leading to the frequent interpretation of Denny’s paintings as architectural images), but the colours are so close-toned that far from emphasizing space, they emphasize the solidarity and unbroken lateral spread and flatness of the surface. The ‘mystery’ of Denny’s paintings is partly a subjective quality—their stillness, their finality and their shadowed, somehow hieratic character suggest that they hold secrets. But as with both the Cohens, though in a more explicit way because of the very nature of his images, Denny calculates his effects as much as he realizes them (as any painter must do) instinctively. This may seem an obvious point to make. But again it is an indication of something in which British painting differs from American: there is no particular effort to look totally instinctive, nor to achieve the American once-and-for-all, wholly uncompromising kind of image stripped of all irrelevance and complication. And this is largely due to a more deeply rooted respect among British painters for the techniques by which a painting is arrived at—for what one might call the craftsmanship of painting. What is frequently labelled an ‘impersonal surface’ would be more accurately described as a pride in technical skill.

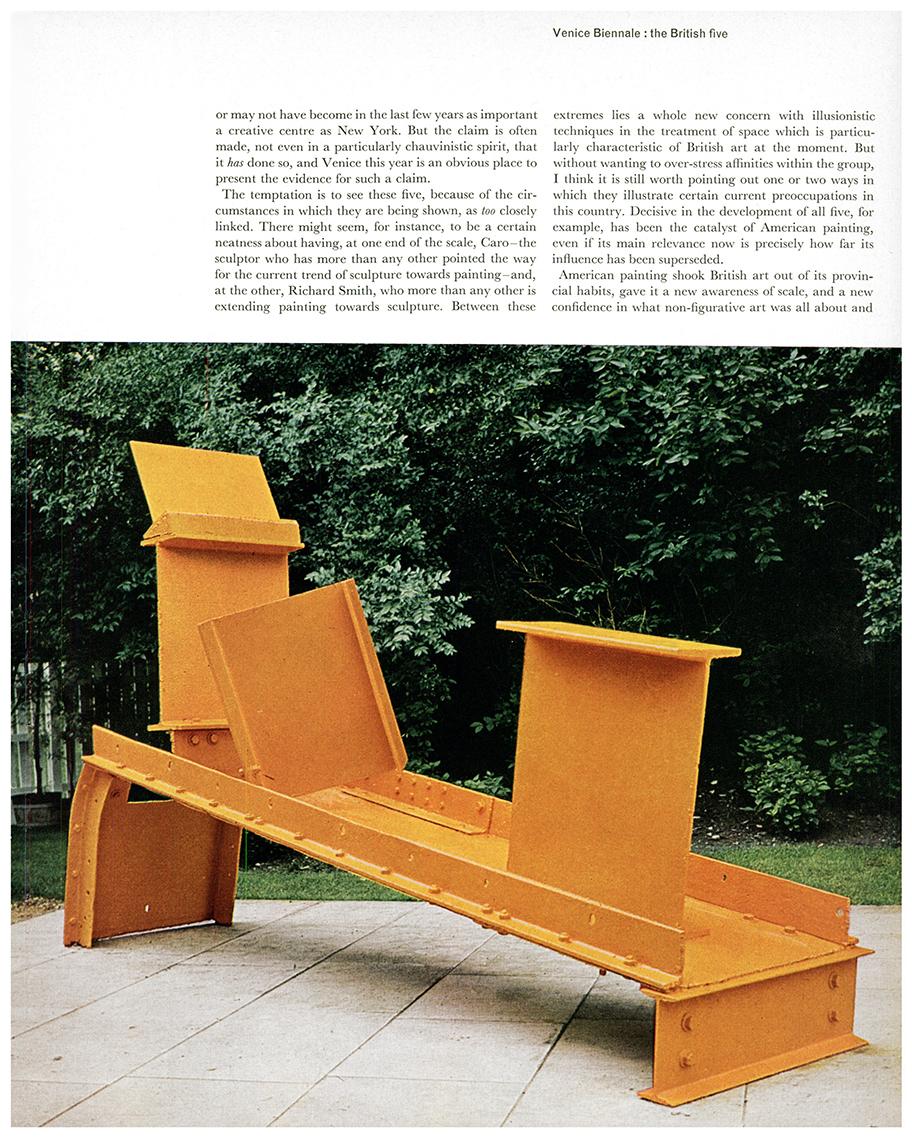

Most of these characteristics could be traced also in Caro’s painted sculpture and Smith’s three-dimensional painting. But what their work more particularly emphasizes is the concern for establishing a close and responsive relationship with the spectator. One of the most fundamental aspects of that revolution in British sculptural ideas with which Caro can be credited, is simply his banishing of the plinth or pedestal and insistence on spreading his sculpture on the floor, thereby making it invade the spectator’s living-space as assertively as a chair or a table. Or rather as assertively as another person. For although Caro’s work has no figurative intention, and although he has said he wants it, however lacking in apparent weight, to be as real and resistant to contact as a chair or a table, what it is about is expressive gesture and what it does is to invade space as uncompromisingly as someone’s stretching out a hand or walking about in it. Caro’s sculpture always tends to look big, not because it has any mass but because its reach is wide. It is a completely open-ended kind of sculpture, which does not gather itself into any formal centre, but continually spreads outwards along its ‘limbs’. Hence its ability to enter into a kind of two-way relationship with the spectator, enhanced by the long-distance contact it makes with him by means of its colour and predominantly visual, rather than ‘sculptural’, appeal.

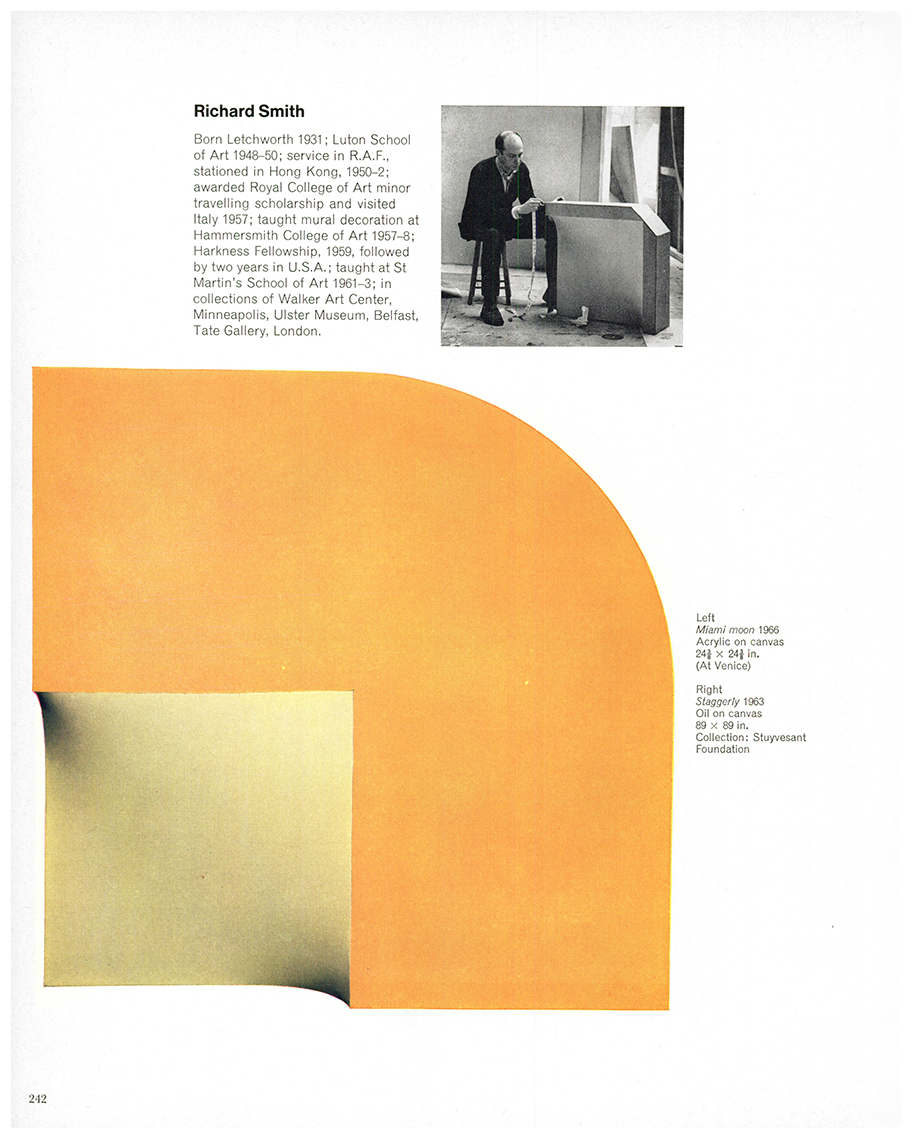

Richard Smith’s background of ‘Situation’ painting and involvement in the visual-communication side of pop art has given him, even when the precise imagery of the giant cigarette-pack or Times Square neon-signs has become less explicit, a continuing bias towards that kind of visual presentation, styling and ‘instant communication’ in his painting which derives from his interest in mass media. London has just had time to see his most recent—and some of his most daring and successful—work at Whitechapel before other examples of it are seen at Venice (not for the first time, Smith’s most interesting developments have been exhibited in New York long before reaching London). In these shaped canvases, combining in their colour both atmospheric illusions of depth and rich blazoning of the surface, Smith’s engagement of the spectator is effected largely by means of techniques alluding to cinema or the theatre. His canvases arch out into space, ‘projecting’ the image on a frontal plane as if on to a screen; or else they simulate, with the aid of concealed fluorescent lighting within the painting, the shape of a theatre proscenium; or in certain groups of three or four paintings, they close in progressively on a formal motif as though through the zoom-lens of a camera, at each stage further emphasizing the encroachment of a particular colour-form on space.

At Venice, Smith’s most recent works are paired with the monumental Gift Wrap of 1963. Caro’s largest exhibit, in the front gallery of the British Pavilion, is the TATE’S scarlet Early One Morning of 1962 (still one of the most controversial pieces of sculpture in the TATE’S collection, although one which the artist himself has always considered among his best). For the most part, though, Venice is not, contrary to usual practice, being used as an occasion for mounting limited retrospectives, but for showing very recent work even ahead of its exhibition in London. Denny’s new paintings have almost entirely broken with the ‘Palladian doorway’ image for which he is perhaps best known. Harold Cohen’s are more, as it were, impressionistic in technique than before, placing the emphasis on an exquisitely flecked and dappled allover ground of colour more than on the grouping of incidental motifs across a canvas. Bernard Cohen’s selection of paintings does not so much indicate a recent development of style as consist of individual extensions of his technical and imaginative range. Together these five artists represent as serious, mature and considered a body of new and original work as could be found anywhere at the moment.

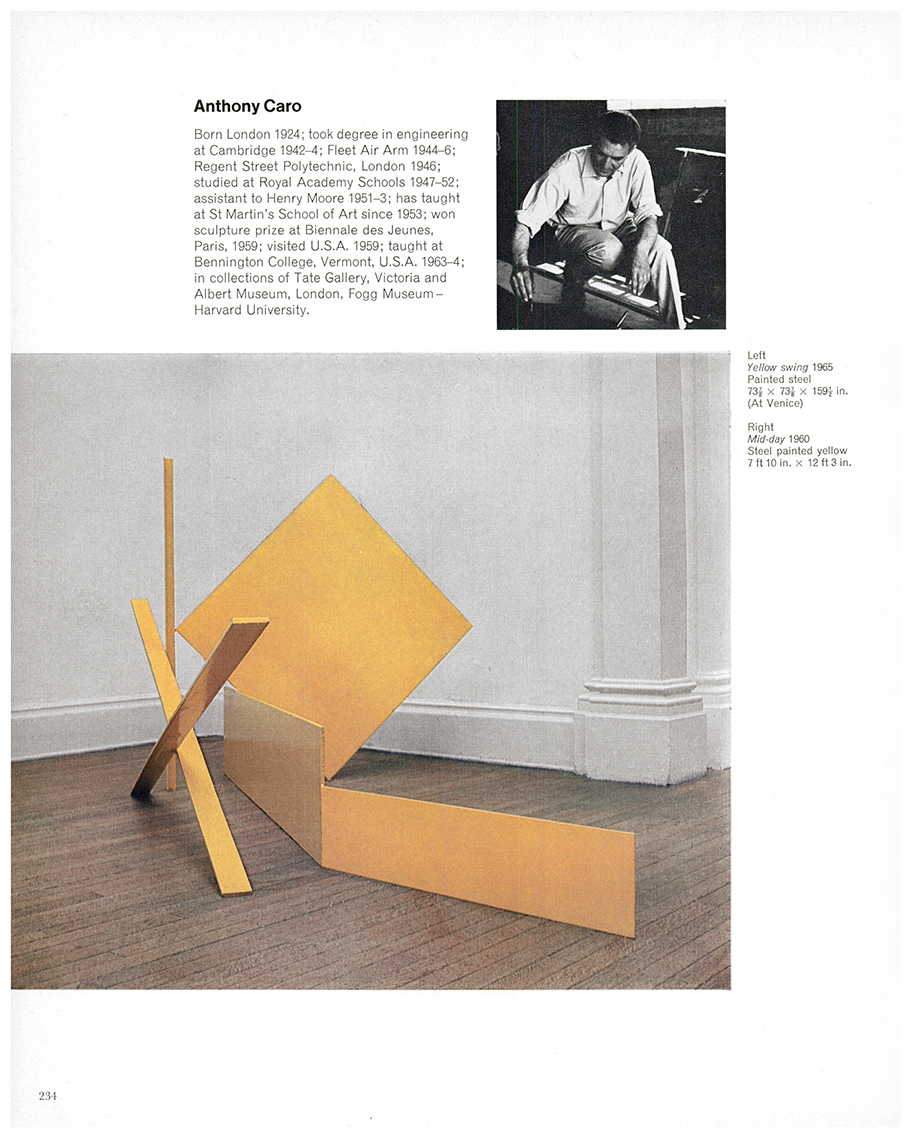

Anthony Caro

Born London 1924; took degree in engineering at Cambridge 1942-4; Fleet Air Arm 1944-6; Regent Street Polytechnic, London 1946; studied at Royal Academy Schools 1947-52; assistant to Henry Moore 1951-3; has taught at St Martin’s School of Art since 1953; won sculpture prize at Biennale des Jeunes, Paris, 1959; visited U.S.A. 1959; taught at Bennington College, Vermont, U.S.A. 1963-4; in collections of Tate Gallery, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Fogg Museum-Harvard University.

Bernard Cohen

Born London 1933; South-West Essex School of Art 1949-50; St Martin’s School of Art 1950-1; Slade School of Art 1951-4; awarded French Government Scholarship 1954, Boise Travelling Scholarship 1956, and spent two years in France, Spain, Italy; taught at Ealing School of Art 1961-4; in collections of Tate Gallery, Museum of Modern Art, New York, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, etc.

Harold Cohen

Born London 1928; Slade School of Art 1948-52; lecturer in art history, Camberwell School of Art, 1952-4; fellow in fine art, Nottingham University, 1956-9; Harkness Fellowship 1959, followed by two years in New York; taught at St Martin’s School of Art, Bromley College of Art, and Ealing School of Art 1961-2; lecturer in painting at Slade School of Art since 1962; in collections of Tate Gallery, Art Gallery of Toronto, etc.

Robyn Denny

Born Abinger, Surrey, 1930; St Martin’s School of Art 1951-4; Royal College of Art 1954-7; Italian Government Scholarship 1957; taught at Hammersmith School of Art 1957-9; visiting lecturer at Bath Academy of Art since 1959; currently at Slade School of Art; in collections of Kunsthalle, Basel, Tate Gallery, London, Museum of Modern Art, New York, etc.

Richard Smith

Born Letchworth 1931; Luton School of Art 1948-50; service in R.A.F., stationed in Hong Kong, 1950-2; awarded Royal College of Art minor travelling scholarship and visited Italy 1957; taught mural decoration at Hammersmith College of Art 1957-8; Harkness Fellowship, 1959, followed by two years in U.S.A.; taught at St Martin’s School of Art 1961-3; in collections of Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Ulster Museum, Belfast, Tate Gallery, London.

Images:

Page 232

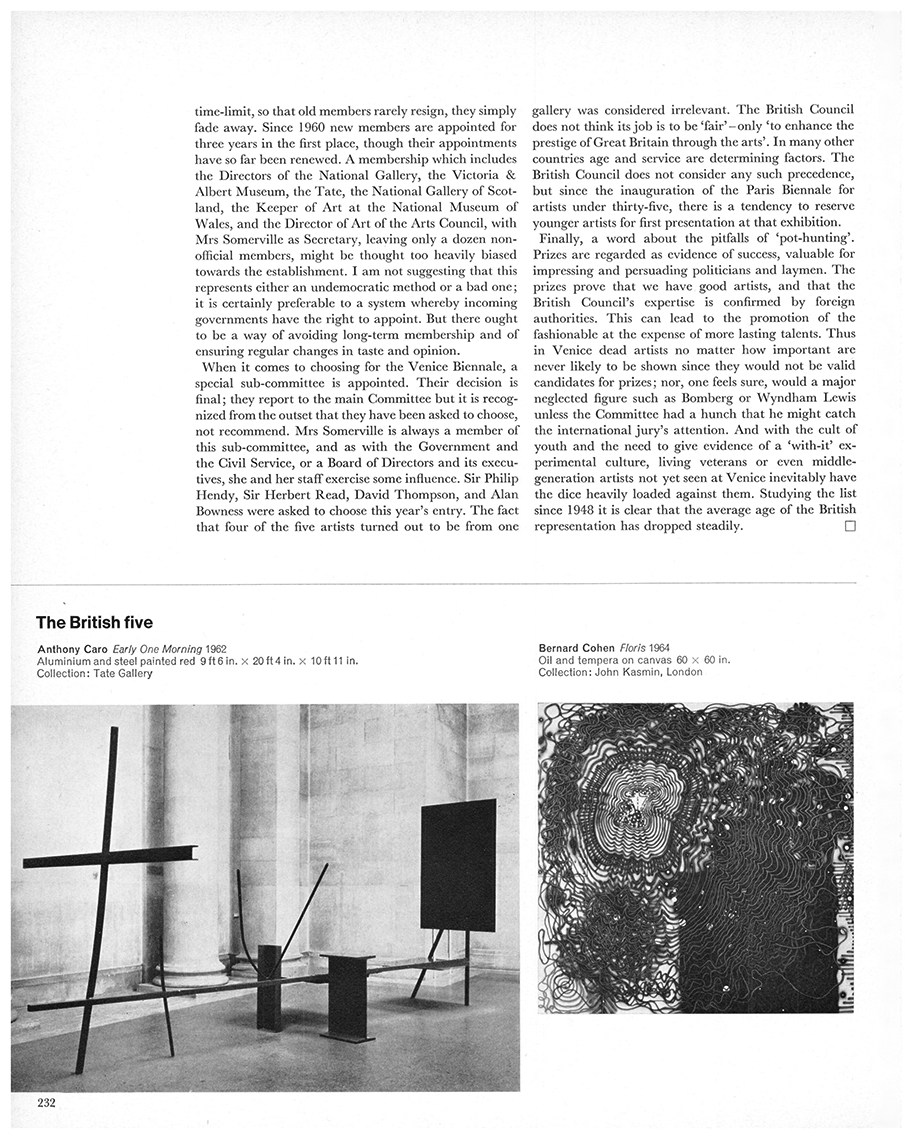

Anthony Caro. Early One Morning, 1962. Aluminium and steel painted red, 9 ft 6 in. x 20ft 4in. x 10 ft 11in. Collection: Tate Gallery.

Bernad Cohen. Floris, 1964. Oil and tempera on canvas, 60 x 60 in. Collection: John Kasmin, London.

Page 233

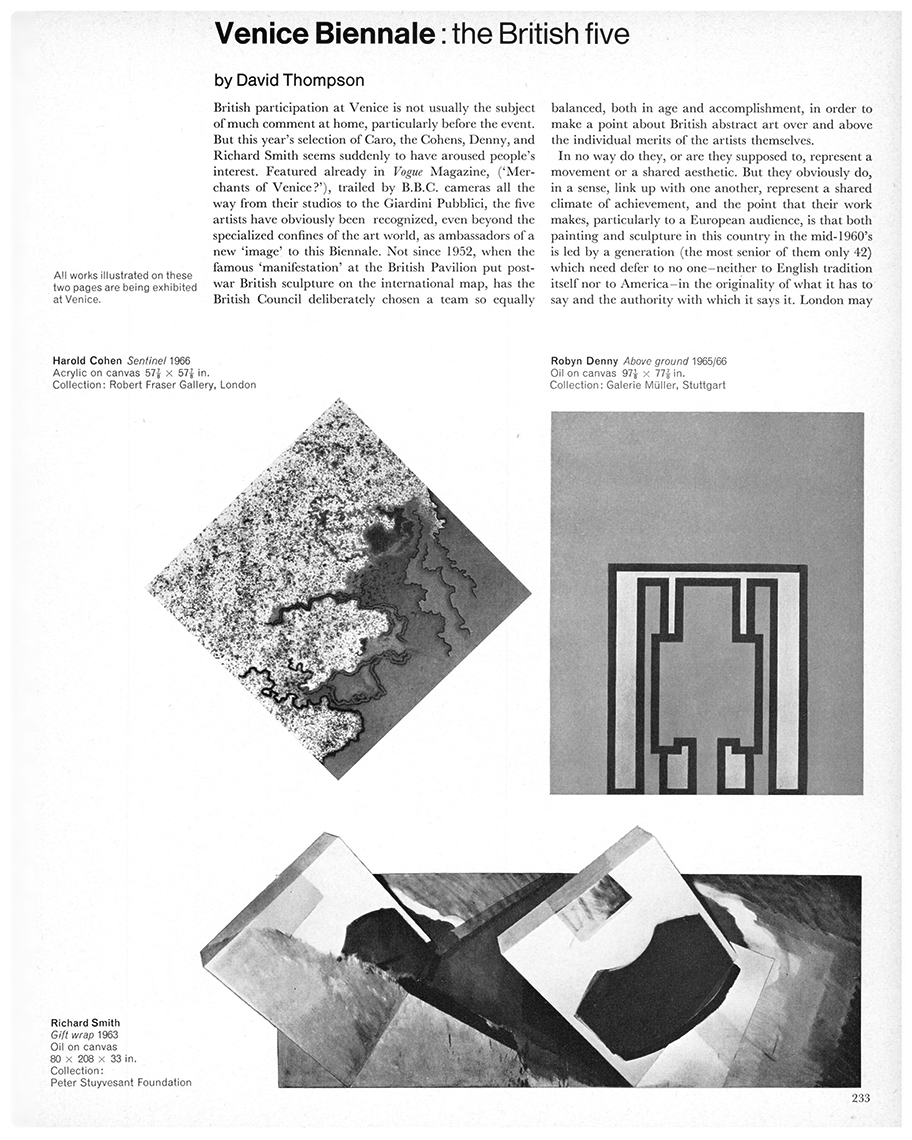

Harold Cohen. Sentinel, 1966. Acrylic on canvas 57 7/8 x 57 7/8 in. Collection: Robert Fraser Gallery, London.

Robyn Denny. Above ground, 1965/66. Oil on canvas, 97 1/8 x 77 7/8 in. Collection: Galerie Muller, Stuttgart.

Richard Smith. Gift wrap, 1963. Oil on canvas, 80 x 208 x 33 in. Collection: Peter Stuyvesant Foundation.

Page 234

Anthony Caro

Left: Yellow swing, 1965. Painted steel, 73 7/8 x 73 7/8 x 159 1/2 in. (At Venice).

Right: Mid-day, 1960. Steel painted yellow, 7 ft 10 in. x 12 ft 3 in.

Page 236

Bernard Cohen

Left: Mist, 1963. Oil and tempera on canvas, 60 x 60 in. Collection: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation

(At Venice).

Right: Red one, 1965. Oil and egg tempera on tempera ground on canvas, 71 7/8 x 96 3/4 in.

Page 238

Harold Cohen

Left: Transit, 1963. Oil on canvas, 68 x 80 in. Collection: Robert Fraser, London.

Right: Pastoral, 1965. Acrylic on canvas, 101 x 112 in. (At Venice).

Page 240

Robyn Denny

Left: First light 1965/66 Oil on canvas 97 1/8 x 77 7/8 in. (At Venice).

Right: Gully Foyle 1961 Oil on canvas 84 x 27 in. Collection: Peter Stuyvesant Foundation.

Page 242

Richard Smith

Left: Miami moon, 1966. Acrylic on canvas, 241 x 241 in. (At Venice).

Right: Staggerly, 1963. Oil on canvas, 89 x 89 in. Collection: Stuyvesant Foundation.