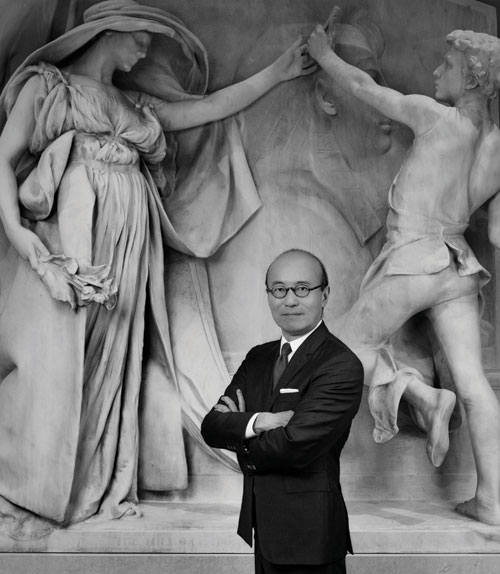

Interview: Harold Koda, curator-in-charge, the Costume Institute, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Charles James: Beyond Fashion

The Costume Institute, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

8 May – 10 August 2014

by CINDI Di MARZO

Charles James: Beyond Fashion celebrates one of the most talented and driven figures in 20th-century couture.1 James did not study design but, as Met director Thomas P Campbell says in his catalogue foreword, James “approached fashion with a sculptor’s eye and a scientist’s logic”. Photographer Bill Cunningham, James’s friend, called him the “poet laureate” and “Einstein” of American fashion, a mix of genre references that hints at the difficulty of pinning James down. His feats of engineering and audacious breaking of the rules (revealed via video screens showing digital cross-sections of his precise geometry) are modern, while the elegance of the attire recalls a bygone era.

Harold Koda, curator-in-charge at the Costume Institute, discusses Charles James’s ingenious designs and complex personality with Cindi di Marzo.

Cindi di Marzo: Thank you for finding time during the flurry of media attention that always attends the spring exhibition and benefit gala to answer our questions. Adding to the excitement, this year’s event marks the opening of the Anna Wintour Costume Centre. Please describe the renovated ground-floor facilities and, perhaps, give us an idea of how you will use the newly allocated space on the first floor.

HK: The Anna Wintour Costume Centre is a complete reconfiguration of the Costume Institute facilities. The updated Conservation Centre, Collections and Archives area with compact storage, an installation section for staging the mannequin dressing and photography, a consolidated Irene Lewisohn Library, a seminar room, and the two galleries reconfigured and “wired” for the latest technology: the Carl and Iris Barrel Apfel Gallery, and our centerpiece, the Lizzie and Jonathan Tisch Gallery. The Apfel and Tisch Galleries will be the focus of our exhibitions, with expanded exhibitions in the spring located on the other floors of the museum, as well. [Met curator] Andrew Bolton and I are envisioning introductory and orientation materials in the Apfel Gallery, and the thesis/conceptually driven projects in the Tisch Gallery. Possible partnerships with other departments, as in the past with European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, will continue with interesting collaborations.

CDM: With the 2009 transfer of the Brooklyn Museum’s costume collection, which includes many marvellous examples of James’s work, and the recent gift of archival materials from his chief assistant and former student, Homer Layne, James must have been an irresistible choice for the 2014 exhibit. Can you highlight a few of your favourite designs?

HK: The mother lode of James designs and archives is now at the Costume Institute. It is difficult to select a few pieces from a body of work or, arguably, masterworks, but I confess to two pieces in the collection that I favour: the black crepe Scarf dress, and his brown/black silk satin Figure Eight dress. Both look as if the gowns were poured over the figure, and both have a reductive and ingenious mastery of cut that comes as a surprise with greater study of the seaming. And there is one [favourite] piece that is not in our collection: the eiderdown quilted white satin evening jacket that the V&A acquired for $6,000 in the mid-70s. That the Met let it slip away is a major curatorial regret.

CDM: James’s name was resurrected in 1982 with the Brooklyn Museum’s the Genius of Charles James exhibit, again in 2011 by the Chicago History Museum with Charles James: Genius Deconstructed, and at the end of May the Menil Collection in Houston will open a James show, but he is still relatively unknown or distantly remembered rather than considered influential and relevant to 21st-century fashion design. Why is that?

HK: Fashion looks forward. Unless you have a living brand, a fragrance, say, or a successful licensee, even the greatest designers will become obscure to the general public.

CDM: James revealed his love of the Regency and Edwardian periods in his most lavish creations. His approach to dressmaking, though, is quite modern in the sense of being experimental and fresh and charting his own course. Some of his designs are inherently “modern”: the “Taxi dress”, a simple wool number held together with a single zipper, and the quilted satin evening jacket which, in hindsight, is the prototype of our ubiquitous puffer jackets. Why was his “Taxi dress” iconic of the era of its first iteration, the 20s, and revolutionary?

HK: James thought outside the box. It is not as though there weren’t robe-like wraps for at-home. But it took James to conceive of such a garment as daywear. Instead of slipping a chemise over the head, or shimmying into it, he imagined the convenience of sliding into it like a bathrobe. Interesting that you address his 1938 puffer jacket. It was a similar strategy, in that he took the idea of a quilted bed jacket, and made it something aesthetically authoritative enough to wear out at night. In both cases, it is taking the comfort and utility of intimate apparel and transferring it to the light of day … or the nightclub.

CDM: Which designer(s) do you feel share James’s flair as an independent thinker operating outside the mainstream fashion world?

HK: Azzedine Alaïa.

CDM: The mention of James’s name conjures images of his sumptuous “Tree,” “Butterfly” and “Four-Leaf Clover” gowns. The cover image of your catalogue – his friend Cecil Beaton’s 1948 photograph of Vogue models clothed in James evening wear, set in the equally luxurious interior of art dealers French & Company – seems to confirm the connection. Then the texts quickly dispel the notion, portraying James as a complex and contradictory man with prodigious creative discipline and an erratic, often disagreeable and combative personality. Which aspects of his character make him both difficult to read and a true artist in his chosen métier, recognised by Poiret, Dior, Balenciaga and many other couturiers as being entirely in a league of his own.

HK: I believe that every great creative personality in any field is wilful and convinced enough of the infallibility of their judgment to be seen by the rest of us as egocentric, bullying, megalomaniacal, etc. In the case of James, I think the ego also had a strand of perfectionism and a standard held for himself and others that could be isolating. Perfectionists are easily bruised by the perceived deficiencies of others.

CDM: I read in Vogue Daily that in the early 70s, when you were an intern at the Costume Institute, James would come in to see his dresses. Did you have contact with him and, if so, what were your initial impressions?

HK: I just heard [former editor-at-large at American Vogue] André Leon Talley recall how he had met James (“BITTER, Bitter, bitter!”) … and the whole social milieu of the 70s. André was fearless and thirsted for experience. I think in my 20s, I was more tentative. When James came into the museum on two occasions, the conservator who I was working for at the time told me that I should hide as [James] would take up my whole afternoon talking about his work. It is to my great regret that I listened to her. Imagine, James expounding on his designs in the Costume Institute collection.

CDM: In the catalogue, you present conservation challenges in a section tellingly titled “Inherent Vice” because the construction of his gowns is problematic. Basically, his voluminous garments are supported by “laminated shells”, layers of antithetical materials such as silk, horsehair, metal, burlap and plastic built with millinery techniques he learned making hats, and guided by his overarching architectural and sculptural vision. Is it possible to restore them to their former glory?

HK: In some instances where the materials are satins, velvets or failles, it is possible to restore them to their former glory. In the case of transparent materials such as tulle and silk georgette, the heartbreaking truth is that they can be conserved, but visually never restored to their former beauty. Conservation is not restoration. If a restorer took off the degrading materials and replaced them with similar materials, you would have an approximation of the original piece. We do not do that, with the exception of severely compromised areas. It is very situational. The mantra for conservators is the preservation of the original and only to employ interventions that are reversible.

CDM: To me, it seems as if wearing one of his gowns must feel like being a bird in a gilded cage. From your research of their documented comments, can you relate how some of his clients felt?

HK: One of my favourite anecdotes comes from Elizabeth Ann Coleman, curator of the 1982 James exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum. She asked a young girl, small enough to wear one of the James designs lent for a fashion show, what it felt like. The teenager said: “It is teaching me how to stand, and how to walk. It is a lesson in beauty.” Elettra Wiedemann, who wore a line-for-line copy of the 10lb [4.54kg] Clover Leaf gown, said the dress was so perfectly poised on her hips that she wasn’t uncomfortable. But she did have the distinct impression that the front pads of her feet were carrying most of the weight.

CDM: His clients included such discerning women as Mrs Randolph (Austine) Hearst Jr, Millicent Rogers and Dominique de Menil, and performer Gypsy Rose Lee. I have heard his relationship with them described in terms of patron and artist rather than client and dressmaker. James aimed to alter a woman’s figure to his ideal, which he did with subtle shifts in the placement of seams and profuse, unorthodox use of darts. He also built his own dressmaker’s models; one with the flexibility to personalise fit beyond anything previously imaginable. Can you describe one or two devices that other designers might never consider, but which became James’s hallmarks and garnered the admiration of a demanding clientele?

HK: James was of the philosophy that the client came in with her body and left with his: create a shape that doesn’t suppress a “defect” but expands its dimensions so the real body is lost in the silhouette; don’t have the body create the shape, have the garment impose it.

CDM: Given his focus on structural engineering, one could lose sight of the sensual quality of his clothing. Can you give us some insight into how he made clothing supported by a fixed armature appear fluid?

HK: James loved surfaces, and fabrics that could be draped, gathered and folded. He also loved the idea of spiralling cloth around the figure. This animated his designs so that a fixed infrastructure might have a roiling surface.

CDM: James adopted the term “metamorphology” from Goethe for his theory of form. How did he explore the concept in his designs?

HK: He attempted to create platonic ideals of the female figure. But he never let well-enough alone. He continued to work on even his most perfected designs, tweaking them, sometimes completely redesigning them. The metamorphosis part of “metamorphology” is his constant revisiting of a shape and evolving it without end.

CDM: James had difficulty with his father, a British military officer who felt that, after his son was expelled from Harrow, the young man would drift, while James’s mother, a Chicago socialite, sent her wealthy friends to him as customers for the millinery shop he opened in America at the age of 19, and later for his couture. So on the one hand, James was encouraged when he discovered something he excelled at and, on the other hand, had a means of retaliation. I have heard you quoted as saying: “Style is a weapon.” Might James literally have used it as such, and flourished by virtue of rebellion?

HK: I wonder if being a sculptor or painter might not have been too respectable for James. But I don’t want to over analyse. Given what I’ve seen of his process, he liked the immediacy of working with fabric, scissors, pins. At first, it was straw and felt that he could shape and mould [in hats]. He might have been too impatient a personality even for clay, although we do have examples of his biomorphic jewellery designs in Plasticine. More than a rebellion against the priggishness of his father, I think he just found a medium that suited him perfectly.

CDM: Although James did not “pass the baton” to a successor, he was concerned to preserve his legacy. He urged his wealthy clients to leave their dresses to the Brooklyn Museum or to fund museum purchases. He also developed courses for the Pratt Institute and the Art Students League of New York, won a Guggenheim Memorial fellowship to write a textbook [not completed], and began an autobiography. The title he selected for the memoir, Beyond Fashion, indicates that he wanted to be remembered for more than clothing. What do you think is his greatest legacy?

HK: James pursued his career as a fashion designer less as commerce than as creative expression. He worked as an artist whose medium was fashion. It is an inspiring standard.

CDM: For our remaining questions, regretfully, I will leave James. He was a fascinating person.

A few months ago, I reviewed Judith Clark and Amy de la Haye’s Exhibiting Fashion for our readers,2 which not only provides a history of fashion’s move into museum programming going back more than 100 years, but traces a trajectory from Cecil Beaton’s groundbreaking 1971 Fashion: An Anthology at the Victoria and Albert Museum to the Costume Institute’s blockbuster 2011 Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty.3 How do you view McQueen [known as “Lee” to his family, friends and colleagues] in the grand scheme of exhibiting fashion?

HK: The McQueen exhibition had work outside the mainstream fashion system: Andrew Bolton selected some of the most provocative and conceptual pieces by the designer. Sam Gainsbury, who worked with McQueen on some of his greatest presentations, created the environments that established Andrew’s curatorial narratives while introducing some of the excitement of McQueen’s defilés. In the end, I feel it was Andrew’s selection of the McQueen designs. A curatorial vision with great work makes for a compelling exhibition. That is not to say that the installation didn’t add to the excitement and the phenomenon, but we have done environmentally compatible installations before. It was the combination of Lee’s work and Andrew’s interpretation visualised by Sam.

CDM: We would also like to hear about the current exhibition Vanitas: Fashion and Art, running until 20 July, which you curated for the Bass Museum in Miami Beach. Is this your first foray outside projects for the Met and the Museum at FIT?4

HK: Not the first, but the smallest. I worked with Germano Celant on the [autumn 2000/winter 2001] Guggenheim’s Armani exhibition. I have a morbid streak, and the Bass was willing to indulge in the idea of fashion and contemporary artworks addressing the theme!

CDM: The theme is intriguing. Can you explain how the show evolved?

HK: A friend of mine is on the board of the Bass and asked if I’d do a show with some costumes for them. Given my work on the Charles James exhibit at the same time I didn’t – actually couldn’t – suggest a large show but [I envisioned] something I thought could be small, even precious, like a reliquary. It got a bit bigger than that, but it has only 20 or so objects. The show was inspired by a skeletal piece [by Dutch fashion designer] Iris van Herpen that we have in the Costume Institute collection. It is like an exquisite fretwork of bleached bird or fish bones aggregated into a short panniered dress. I bullied my colleagues into purchasing it for the collection, and now we have the earliest 3D-modelled high-fashion garment ever produced. That dress was the start of the process. Sometimes it is an idea [that sparks an exhibit], but in this instance it was an object.

CDM: The Bass show does sound like quite a contrast to the James exhibition. Thank you for telling us about it, and for your comments on James. You have certainly helped to unravel the mystery – and mastery – of the man.

References

1. The 264-page hardback catalogue for Charles James: Beyond Fashion is published by Yale University Press, price US$50/£35.

2. Behind the Scenes at a Museum: studiointernational.com/index.php/behind-the-scenes-at-a-museum-exhibiting-fashion-before-and-after-1971

3. Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty: studiointernational.com/index.php/the-dark-side-of-love--alexander-mcqueen-savage-beauty

4. Koda worked at the Edward C Blum Design Laboratory of the Fashion Institute of Technology, serving as associate curator in the costume collection from 1979 to 1982, as curator of the costume collection from 1982 to 1990, and as director from 1990 to 1992. In 1993, he joined the Costume Institute, where he had been an assistant earlier in his career, for a four-year stint as associate curator, then returned in 2000 as curator-in-charge after earning a master’s degree in landscape architecture from Harvard. At FIT and the Met, he worked for Richard Martin, author of an introduction to James’s work published by Assouline.

.jpg)