Although many pieces of fine porcelain were produced, the imperial judges chose only flawless examples. The reputation of Jingdezhen porcelain was so great that only the best could be offered as an example. As a result, a large number of porcelains were rejected and subsequently destroyed so that they would not fall into the hands of commoners. Certainly, protecting the reputation of such esteemed vessels was at stake, but the authorities were also fiercely guarding the techniques used to produce them. Rather than merely discard cast-offs, the rejected porcelains were broken into pieces and buried.

The Sackler exhibition featured, in reassembled form, such broken, buried and rejected porcelain objects, including works produced during the reigns of Ming emperors Hongwu, Yongle, Xuande, Zhengtong, Chenghua, Hongzhi and Jiajing. The variety of works include bowls, jars, cups, plates, building hooks and plum blossom vases. Some are considered by scholars as rare and very precious.

It is unfortunate that a lack of historical documents leaves many questions unanswered about how the craftsmen worked at the imperial kilns. We know they were employed by the royal family, then assigned to one of several workshops. The workshops functioned around specific objects: bowls created in one, jars in another, for example. As in assembly-line production, each worker was responsible for a specific step. Their works were then and are now considered to be fine art, but the method of production did not put creative control within the hands of any one craftsman. The ultimate judge of quality was a representative of the royal family, whose seal of approval meant an object would eventually become among the most prized in some collector's holdings.

Most of the objects in the Sackler show were culled from several archaeological excavations in Jingdezhen conducted from 2002 to 2004 by a joint team of researchers from the School of Archaeology and Museology at Peking University, the Cultural Relics Archaeological Research Institute of Jiangxi Province and the Jingdezhen Porcelain Archaeological Research Institute. By exhibiting these rare discoveries, the Sackler Museum has provided valuable materials for further study on Ming porcelain manufacturing techniques and made available to researchers important information about the imperial kiln managerial system of the Ming Dynasty. While much remains unanswered, the exhibition has added to our knowledge of the elusive history of Jingdezhen porcelain.

Cao Hong

The Arthur M Sackler Museum of Art and Archaeology, Peking University, People's Republic of China

Box with red glaze. Ming dynasty Yongle (1403-24). Height: 9.7 cm. Diameter at mouth 19cm. Diameter at base: 14.5 cm. The box covered with red glazed but inside is white glazed. There are floral designs around the box but unclear.

Incense burner with black glaze. Ming dynasty Yongle (1403-24). Height: 21.2 cm. Diameter at mouth: 14.5 cm. This Incense burner has two ears and three legs. The body is incised with designs of grass and chrysanthemum but unclear. It is covered with red glazed but uneven.

Blue and white and underglazed red cloud dragon design vase (Mei Ping). Ming dynasty Yongle (1403-24). Height: 34.1 cm. Diameter at mouth: 6.7 cm. Diameter at base: 15.9 cm. This vase (Mei Ping) has a very small mouth, short neck, wide shoulder and small base with a round rim. The mouth is so small that only a single stem of plum blossoms would fit inside. This type of porcelain has thus been named 'Mei Ping', or 'plum-blossom vase'. In fact, vessels of this type were wine containers and very popular during the Ming and Qing dynasties. The design of this vase is uniquely done with blue and white mountains and waves in the lower part, an underglazed red dragon on the main body and clouds on the shoulders.

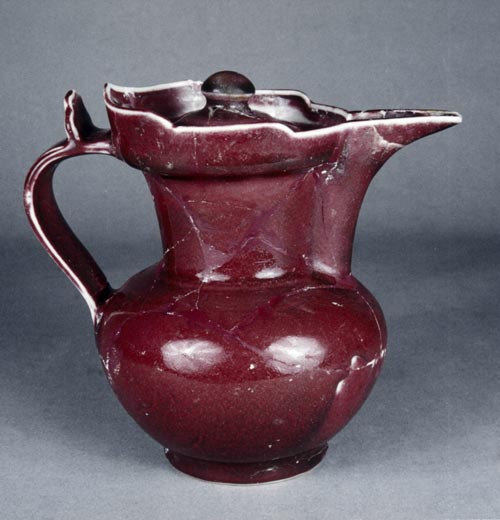

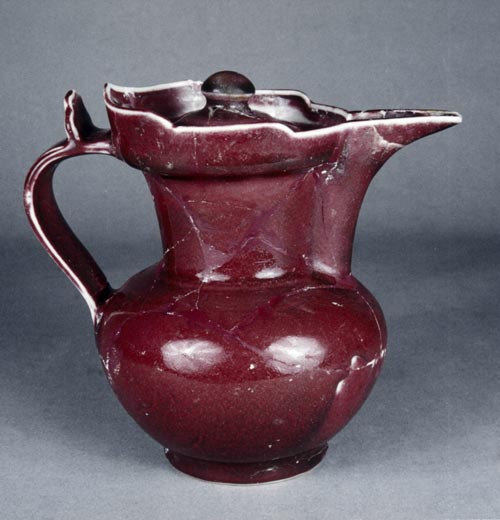

Monk's cap-shaped pot with red glaze. Ming dynasty Yongle (1403-24). Height: 19 cm. Diameter at mouth: 11.2 cm. Diameter at base: 8 cm. The mouth of the jar seemed slightly like a cap of monk and so it was named. It is covered with red glazed but uneven.