Guggenheim Bilbao | 2 October 2019 – 19 January 2020

by DAVID TRIGG

If patience is a virtue, then Thomas Struth must be approaching sainthood. The German photographer’s practice – more than 40 years of which are surveyed in this expansive exhibition at Guggenheim Bilbao – is built on careful observation and waiting. Hours are spent composing and setting up shots; he watches for the light to shift, for streets to empty and for museum visitors to arrange themselves in his viewfinder. There are no spontaneous “decisive moments” here, just premeditated and meticulously planned ones. Struth (b1954) invites us to join him in this game of protracted looking. Certainly, his large-scale photographs reward those who slow down and linger, but with more than 100 works on display, you will be forgiven for indulging in at least a little cursory viewing.

A slew of black-and-white cityscapes opens the show, the earliest of which date from 1977, when Struth was studying at the Staatliche Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. These deserted London and New York streets scenes are suffused with the influence of his tutors, Bernd and Hilla Becher, whose own oeuvre documented industrial architecture. Echoes of the Bechers’ deadpan approach appear throughout the show, but especially in works such as Clinton Road, London (1977), and Crosby Street, Soho, New York (1978). Focused on the built environment and bereft of people, they are unnerving and almost post-apocalyptic in their stillness.

[image2]

Elsewhere are European and East Asian cities, including the arresting Ulsan 2, Ulsan (2010), in which a soulless sprawl of South Korean high-rises stretches into the mist. Struth refers to these images as “unconscious places”, referring to the visible traces of the subliminal social processes that are inscribed across urban environments; though absent of people, they attest to human presence and endeavour.

Mingled with these are a selection of Struth’s intimate family portraits. The series has its roots in a research collaboration with the German psychoanalyst Ingo Hartmann, who invited patients to incorporate family pictures into their therapy sessions in order to explore how such images might reveal particular narratives about family life. Struth’s own portraits invite similar analyses: what, for instance, can body language teach us about the strained familial relationships in The Bernstein Family, Mündersbach (1990)? Or what about those of The Shimada Family, Yamaguchi (1986)? Though the ensembles invite much speculation, they lack the emotional depth and dignity seen in works such as Kyoko and Tomoharu Murakami, Tokyo (1991), and Eleonor and Giles Robertson, Edinburgh (1987). The way Struth has carefully composed these latter portraits of married couples speaks at once to his meticulous attention to detail and debt to painting. To learn that Struth studied under Gerhard Richter before turning to photography should come as no surprise.

[image6]

It was in the late 1980s that Struth began setting up his large-format camera in the world’s major art museums to explore the relationship between paintings and their viewers. In Louvre 4, Paris (1989), a group of visitors stand with their backs to Struth’s camera as they gaze at Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1819). Here, dispassionate viewing contrasts with the horror of the romantic masterpiece, yet Struth sets up a formal continuity between the painting and spectators by aligning them on a diagonal axis that follows Géricault’s composition. Similarly, in Art Institute of Chicago I (1990), the poses of the Parisian figures in Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884) are echoed by contemporary viewers. Best of all is the monumental Art Institute of Chicago II, Chicago (1990), in which a woman stands with a pushchair in front of Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day (1877). Her clothing rhymes uncannily well with the painting’s palette, as do the gallery’s floor tiles, which seem to bring the wet cobblestones of 19th-century Paris into 20th-century America.

One can only imagine how long Struth must have waited to accomplish his remarkable Museum Photographs, which are, in essence, about interrogating the act of looking. In this way, they trouble the line between the intentional and the incidental, the artificial and the natural. Similar ideas are explored in his recent Disneyland series. Mountain, Anaheim (2013), for instance, shows the theme park’s famous 1/100 scale model of the Matterhorn – a Swiss landmark reimagined as a rollercoaster.

[image8]

Elsewhere, Canyon, Anaheim (2013), shows a hyperreal desert landscape with a race track running through it. Even after examining this enormous work’s luminous detail, the ratio of natural to man-made elements remains uncertain. Struth excels at this kind of ambiguity, but is less compelling when pointing his lens at purely natural landscapes. For example, New Pictures from Paradise – his late 1990s series depicting fragments of rainforests, jungles and woodlands – feel flat, lacking the formal allure seen elsewhere.

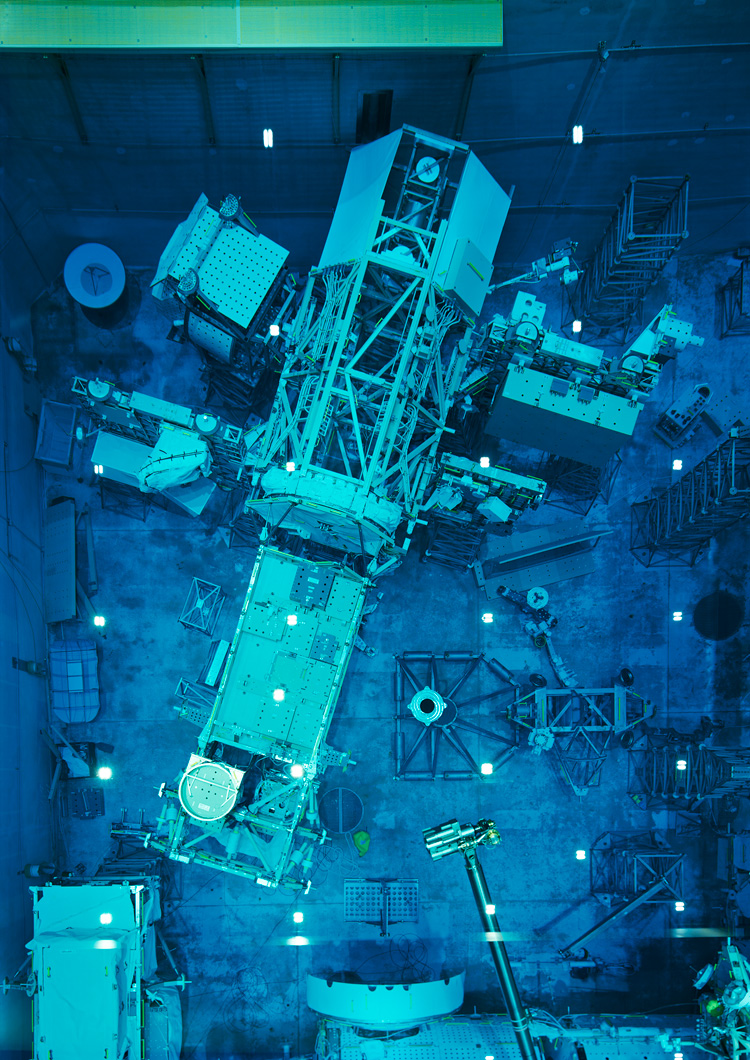

Struth’s photographs teach us much about our place in the world and yet there are times when he leaves you fumbling in the dark. This is the case in the final room, where selections from his Nature & Politics series ramp up feelings of perplexity. These enormous prints depict super-complex machinery and hi-tech apparatus in research centres, aerospace laboratories, medical facilities and science labs. They speak to the way technology has advanced far beyond our ability to comprehend it. Even the titles don’t help. Take Stellarator Wendelstein 7-X Detail, Max Planck IPP, Greifswald (2009), which shows a bewildering tangle of ducts, wires, pipes and sundry industrial elements. While no amount of staring will unlock the secrets of this dense and alienating image, its visual rhythm recalls Jackson Pollock’s wild splatterings, reminding us again of Struth’s painterly eye.

Among the most arresting – and unsettling – of these images is Figure 2, Charité (2013), which shows an anaesthetised woman lying on an operating table about to undergo brain surgery. A network of wires, tubes and cables connect her body to banks of medical machinery. It is a powerful testimony to the role that advanced technology now plays in prolonging life, but it also speaks to our fragility and the fact that human ingenuity has yet to conquer death. Indeed, the exhibition ends by bringing you face to face with mortality, through a haunting series of still lifes depicting dead animals. The creatures, photographed soon after death from natural causes, rest serenely in Berlin’s Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research. There is nothing ghoulish here; each animal and bird, whether zebra, bear, fox or eagle, is treated with dignity and respect, shown before decay takes hold.

[image12]

In highlighting photography’s capacity to memorialise and preserve (a lesson learned from the Bechers), these works underscore the relationship between photography and death. As Susan Sontag eloquently wrote: “Photography also converts the whole world into a cemetery. Photographers, connoisseurs of beauty, are also – wittingly or unwittingly – the recording-angels of death.” Struth waits patiently for new arrivals at the Leibniz Institute – literally waiting for death. As a kind of memento mori, the project nods to the fact that the inevitable awaits us all. All the more reason, then, to slow down and take in the view.