Royal Academy of Arts, London.

June-August, 2007

Impressionists by the Sea

Royal Academy of Arts

7 July – 30 September 2007

The Phillips Collection, Washington DC

20 October 2007 – 13 January 2008.

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford

9 February – 11 May 2008.

The Royal Academy in summertime is a national institution. As well as the Summer Exhibition this year, there is Impressionists by the Sea, an exhibition of 70 paintings produced at the end of the nineteenth century in France, which charts the economic and social developments in France that brought about the transformation of the seaside. The exhibition will travel to America this autumn.

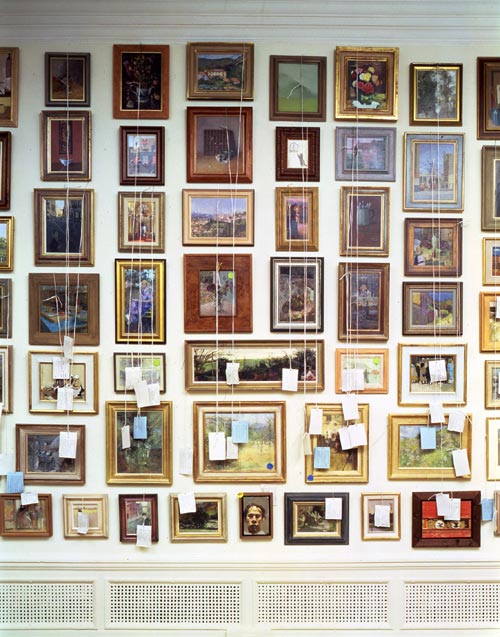

The Royal Academy's popular Summer Exhibition has been an annual event since 1768. It is the largest open contemporary art exhibition in the world, drawing together a wide range of new work by both established and unknown living artists. Held annually since the Royal Academy's foundation it is a showcase for art of all styles and media. It encompasses paintings, sculpture, prints and architectural drawings and models. Today, over 1,200 works have been selected from over 12,000 entries, representing some 5,000 artists. Following the long Academy tradition the exhibition is curated by an annually rotating committee, whose members are all practising artists.

The method of choosing and hanging the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition is "an amazing, idiosyncratic, and splendidly unbureaucratic, even radical way, to insist on. And yet, in its essentially British pattern it has something in common too with Crufts Dog Show, say: or the Chelsea Flower; en masse to apply an obsequiousness of curatorial efficiency over detail and category: or else to go over to an acquiescent omnivalence designed to suit all tastes. Or something completely different. Or more or less the same."1 Spot the treasure, pick up a bargain, this year is no disappointment in spite of having seen the process and many of the works in the exhibition on the BBC 2 documentary that followed the progress of the great show.

Paul Huxley, one of the senior hangers, was quick to point out that this year's show was different, for it included the largest painting ever exhibited, by David Hockney RA, and the heaviest painting ever hung, by Honorary RA Anselm Kiefer, "a combination of heavily encrusted mud, paint, a submarine modelled in lead, and a thorn bush, roots and all." The Kiefer required two cranes and seven technicians. David Hockney's painting is spectacular in its scale and in the appropriate relationship with the gallery space. To view the work from the distance of another gallery is a wonderful experience. Hockney's landscape, Bigger Trees near Warter or/ou peinture sur le motif pour nouvel âge post-photographique, captures what the eye sees but which a camera cannot capture. Made up of fifty canvases of the same size, Hockney's massive painting was painted in the open air in situ, although it was necessary to use a computer to see everything at once. The work took an entire day to install with Hockney there to give instructions. The result is a triumph. What is remarkable in the hanging is that although the Hockney and the Kiefer dominate in terms of scale, they still do not eclipse the great number of works by other artists. The Adrian Berg paintings next to the great Hockney, manage to hold their own, a tribute to the works themselves and to the skill of those hanging that impressive gallery.

The excitingly modern and the traditional manage as bed-fellows at the Royal Academy as no where else. The giants of the contemporary world: Robert Rauschenberg, Antoni Tapies, Lucien Freud and Frank Auerbach as well as complete unknowns. There is a festive spirit, and a languid summery feel to the wide range of exhibits. This year is the first to include a gallery devoted to photography, an excellent innovation. The architects' room is painted blue, giving a cohesive feel to the range of drawings, models, plans and photographs. This year's theme was light, and in the hang there is a sense of light and space, in spite of the extraordinary number of exhibits. The sculpture gallery has to cope with a wide range of sizes, as Bill Woodrow, who hung this gallery with Nigel Hall and David Mach, pointed out: "Everything here is hugely varied in scale and material, and we've had to fit one piece in with another while allowing each work to speak out in its own voice."2

Norman Ackroyd was in charge of the gallery for prints, and there he managed to give a sense of more space than usual, when in fact some 30 extra works were hung. Five of Norman Ackroyd's own atmospheric etchings are included in the print room, where he said he was knocked out by the quality of works in woodcuts and linocuts. "There appears to be a renaissance in the use of these techniques", he observed, "and it was truly reflected in the prints we got for selection".3 Anthony Green, RA observed the manner in which the Royal Academy was moving with the times: "If visitors of thirty years ago were suddenly confronted by this year's show they'd scarcely recognise any of it. And if visitors of half a century ago, when the Summer Exhibition was still put together by narrow-minded reactionaries, could come back now, they'd probably be so confused and shocked that they'd all have nervous breakdowns. We are, after all, an academy for today, for the twenty-first century."4

The Summer Exhibition provides a fitting obituary to Royal Academicians who have died in the previous year. Two quite different artists, in terms of their work, Sandra Blow and Kyffin Williams are given a fitting farewell; their work reflects two strands of post-War British art – figuration and abstraction. As Frank Whitford, writes, "Kyffin Willaims and Sandra Blow exemplify the pluralism of post-war British art. They also testify to the inclusive nature of the modern Royal Academy: it welcomes and accommodates a multiplicity of styles and approaches, and its exhibitions attract a public with a wide variety of tastes. The differences between the art of Williams and Blow are not irreconcilable, however, and they are lessened by some unexpected affinities, as we shall see."5 The Welshman, Kyffin Williams was happiest in touch with his roots, but in fact was raised and educated in England. He came to art relatively late, after being invalided out of the army for epilepsy. In fact, the army doctor thought him'abnormal' and therefore suggested that he take up art. He applied to the Slade. "At a time when emphatic expressivity and self-revelation were generally deemed suspect, Williams worked in an unapologetically emotional way, inspired by the early, earthy Van Gogh (a fellow epileptic), the Fleming Constant Permeke, Chaïm Soutine, and above all Georges Rouault."6 His limited palette of mostly black, greys and white changed little in his oeuvre, he occasionally introduced a vibrant red or pink. The way in which he introduced colour to a tonal painting, Whitford claims made him a superb colourist. Williams opposed Conceptual Art and much art since the 1950s. He also abhorred the cult of the artistic celebrity. Williams remained an individual and a loner.

Sandra Blow, by contrast was a more international artist who developed an abstract language over a long career. She was elected an RA in 1978. She studied in London and Rome, her early training greatly affected by the war and the bombing of London. She was greatly influenced by the German-American, Hans Hofmann, and in response, embraced abstraction. The Italian Alberto Burri was of greater influence still. Whilst living with him she employed all sorts of materials - discarded fabrics, tar, plaster, and while this launched her on a vastly new path to her more traditional training in London, she felt overwhelmed by Burri's influence and returned to London in 1948. Blow was successful in London where she had her first solo exhibition in 1951; in 1958 she won the International Guggenheim award and was exhibited at the Venice Biennale.

Collage and experimental abstract works became Sandra Blow's style. Her work was spontaneous yet came about through endless trial and error and utter dedication. She aimed for what was,'a thrilling rightness'. Her work was bold, radiant and life-affirming. In 1994 she moved to Cornwall where she found an empty furniture warehouse which she turned into a large studio. She worked there until her death last year, in August 2006. Frank Whitford wrote, "the most important link between Blow and Williams was their attitude to nature. Williams's art was rooted in his observation of the world and its effect on his emotions. Blow, too, maintained that nature was an essential factor in the shaping of her painting. … Williams obviously saw himself as a traditionalist, but so too, perhaps unexpectedly, did Blow – despite her liking for experiment. She once described herself as an'academic abstract painter', in the sense that her work was chiefly concerned with such factors as balance and proportion,'issues that have been important since art began'. Williams would have understood what she meant."7

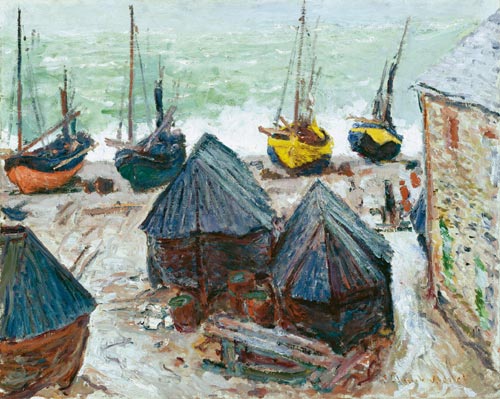

Impressionists by the Sea, charts French painting on the north coast from early picturesque views of storms and fishermen and women at work in their traditional roles, to the celebration of light and modernity in the work of Eugene Louis Boudin, Gustave Courbet and Claude Monet. John House, the curator makes a detailed study of the social changes that brought about a transformation of the coastal areas of northern France. During the nineteenth century, the north coast of France, was transformed from primarily fishing communities to tourist destinations. The coast in painting was always important as it was in literature. The romantic tradition of drama at sea, the mortal danger faced by fishermen against the celebration of nature's bounty. Basic survival was set against the constant threat of hardship and danger in the ritualistic processes of fishing at sea. There have always been Biblical connotations of the sea as a constant threat, and yet also, representing innocence and happiness. In the career of Monet it is possible to see a range of different approaches, for he changed direction from his peopled paintings to the dramatic images of rock faces and the drama of the sea itself.

The exhibition, Impressionists by the Sea, explores the painting in northern France between the 1850s and 1890s. Predecessors are included to set the scene in the works of Boudin and Courbet. The scale of the development of small fishing villages to flourishing coastal resorts can be illustrated in fact. The population of Trouville was 2,000 in 1830 and 5,200. In the summer months, some 20,000 visitors transformed the atmosphere. The development of the railways was one of the most significant factors, and there followed the building of villas, grand hotels and casinos. The local population were obliged to shift from fishing to the service of the crowds of city dwellers who descended upon towns such as Trouville, Deauville, Etretat and Honfleur.8

In the early stages of the development artists sought to capture the traditional way of life on the coast, to ennoble the peasants and draw contrast to city life where a communion with nature was seen to have been compromised. The heroic life of those who worked in the sea, by contrast, was seen as an authentic existence requiring high moral calibre. There was not a cohesive response, by artists and writers, to the subject matter that drew so many artists to the coast. Few visitors can have been aware of the extent of financial threat of life at sea, or the harsh realities of the danger of long periods at sea. In the summer months in France, most of the men from the French coastal ports, were in fact in Canada, in the Newfoundland area where stocks of fish were at their best. The women of the villages combed the shores for shell fish and to city visitors, their life must have seemed in harmony with the rhythms of nature. The dramatic religiosity and supernatural fascination with creatures from the deep is ironically more closely addressed a hundred years later by the Scots artist, John Bellany, RA. David Hopkin's essay, "Fishermen, Tourists and Artists in the Nineteenth Century: The View from the Beach", gives a scholarly appraisal of the complex issues involved for artists and local populations.9

Eduard Manet, Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot and Pierre Auguste Renoir are among the artists shown in this splendid exhibition. It was very much the individual artist's response that determined the works rather than a cohesive response to the subject matter. Renoir's peopled canvases, for example, Beach Scene, Guernsey (1883) or Berthe Morisot's Children at the Seashore, (1885) could not be more different to the stark landscape paintings of Monet, where he focussed entirely on the sea and rock faces. Formal compositions and images of great psychological tension and alienation - these works enabled Monet to take stock of his life which was characterised by hardship and tragedy following the illness and death of his wife.

A brief holiday with his brother on the Normandy coast in the autumn of 1880 proved a turning point in Monet's career. The dramatic coastline and cliffs were the impetus for his work over the next four years. His work was re-invented by the experience of the cliffs and the sea there. A greater freedom of handling the paint, at times a sense of abandon in the act of creation. For the first time he was released from serious financial worries by the support of his Paris dealer, Durand-Ruel.

The lease on Monet's house, came to an end in October 1881. After a few months in a temporary house in the same village, they moved to Poissy. There Monet and Alice Hoschedé made a fresh start with the children from their respective marriages. Although Monet had a fine view of the Seine from the studio of the large house there, he disliked the town. He travelled to Dieppe on the coast, a favorite village for numerous artists at the end of the nineteenth century, but Monet was dissatisfied there too. Pourville, another fishing village did however suit him, and he painted prolifically there. Alice and the children from their two families joined him there during the summer months.

Pourville provided a range of subjects: cliffs, fishing nets, a church and the sea itself. It was here that he really began to work in series for which, in his later life, he became so famous. He painted many subjects of the same subject in differing conditions and returned again, and again to the coastline there. In the summer of 1882, at Pourville, the traditional fishing nets provided Monet with the visual impetus to explore his love of Japanese woodblocks.

The asymmetrical composition has clear, if generic, echoes of Japanese colour prints, with the viewer poised above the space without visible foothold, and the wedge of cliff jutting into the corner of the picture. Monet has used this format to emphasise the contrast between foreground and distance, and to give a vivid sense of the wide space of the bay. The recession into space is conveyed by means quite unlike the flat planes of the Japanese print – by subtle nuances of colour and touch that lead the eye out across the sands, through the clusters of boats, and to the dimly indicated far shoreline.10

In 1883 on a short trip to Etretat Monet painted twenty canvases of the coast using the cliffs and vast Manneporte, "the massive natural structure of a great portal punched by the sea through the jutting shoulder of rock". It was quite inaccessible from the land, requiring Monet to reach it via a damp, long tunnel. Two large canvases were produced on this challenging subject, one of which he was not satisfied with and so it stayed in his studio. The Entretat paintings are key works in Monet's career. Richard Thomson writes:

The Manneporte is a truly striking composition. Its great sculptural form gives it the impact of the sublime. In the cramped confines of the cliff-rimmed bay, working in carefully timed sessions to avoid being stranded by the tide in a treacherous spot, Monet chose to bring the great portal into close focus, so that its huge arch fills the centre of the canvas, with views far out to the sea on either side…If he successfully evoked the sculptural sublime of the Manneporte, this was not to the detriment of naturalism and the actuality of looking. His sense of local colour was acute, nowhere more than in the sea's pearly green just below the horizon. He respected natural features, such as the flat strata set in the geological layering of the rock and chalk, or the streaks of deep brown soil spilling down from above. And he caught the moment, with silvery spray breaking on the rocks, paradoxically painted in quite matted strands.11

The exhibition in fact reveals that although the transformation of coastal France, came about as a consequence of it becoming a resort, painters interest in the holidaymakers was relatively short-lived. The artist as pioneer and as a loner whose confrontation with nature was exemplified by the work of Claude Monet.

The Impressionists' virtual abandonment of the imagery of the modern beach should also be viewed in a wider historical frame. [T]he landscape painter played the crucial role of pioneer in the'discovery' of the Normandy coast in the years before 1850. This role was by definition a solitary one; the painter stood alone surveying a hitherto undiscovered land or, rather, a landscape whose potential as a subject for painting had not previously been appreciated, and appropriated by other painters.12

Impressionists by the Sea puts the viewers into a position where they can experience through artists' eyes the landscapes and environments that surround us all. With heightened perception and depth of feeling, viewers are encouraged to look and feel a little closer, to walk as if on a pier, to sit as if windswept by enchantment and contemplation. The Impressionists, with their sunsets, cliffs, sand, rocks – take viewers away from the metropolis and give them an impression of another way, a frontier of unknown journeys and secret escapes, to counter the overwhelming urbanity that engulfs the visions of many.

Dr Janet McKenzie

References

1. Michael Spens, "Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, 2000," Studio International, e.journal, August 2000.

2. Quoted by Frank Whitford, "Introduction", Royal Academy Illustrated, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2007, p.10.

3. Ibid, p.10.

4. Ibid, p.11.

5. Ibid, p.12.

6. Ibid, p.12.

7. Ibid, p.15.

8. John House, "Representing the Beach: The View from Paris", Impressionists by the Sea, Royal Academy, London, 2007, p.15.

9. Ibid, pp. 31-37.

10. John House,'Catalogue Entries' for Monet, The Cottage at Trouville, Low Tide, (1881), ibid, p.137.

11. Richard Thomson, Monet: The Seine and the Sea, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, 2003, p.148.

12. House, "Representing the Beach", op.cit., p.26.