The British Museum, London, 17 April-7 September 2003

In his Preface to the catalogue, the Director, Neil MacGregor states:

For individuals, as for communities, it may be said that memory is identity. At the very least it is an essential part of it. To lose your memory is, quite literally, no longer to know who you are, and we have all witnessed the consequences both in individuals and in communities. For both, a life without memories is so diminished as hardly to count as life. All societies have therefore devised systems and structures, objects and rituals to help them remember those things that are needful if the community is to be strong - the individuals and the moments that have shaped the past, the beliefs and the habits which should determine the future. These monuments and aide-mémoire point not only to what we were, but to what we want to be.1

In the past few decades there has been an astonishing growth in the establishment of museums worldwide, of heritage centres, of genealogy. The present bibliography on the subject of memory is symptomatic of a broad and specialised interest in these aspects of culture.

Aide-mémoire, explored by the first section of the exhibition reveals that all societies have their own forms of remembering and celebrating events: personal, momentous, historical. Aide-mémoire existed in prehistoric cultures. If anything, it played a more important role than in cultures with written records. In Greek society, 'memory is the progenitor of knowledge, history, mathematics, astronomy, eloquence and the arts of persuasion. It is a fundamental, god-given and god-like attribute'.2 In Greek and Roman societies, 'memory is identified with a spectrum of laudable and basic human and civic duties: knowledge, learning, constancy, reliability'.3

With the present industry in the field of museum buildings and philanthropy in the field of arts and monuments, a heightened consciousness of the role of memory has become a dominant theme for the architects of contemporary museums and memorials. Daniel Libeskind's Jewish Museum in Berlin is a remarkable example of how architectural language can be employed as the subtlest poetry to allude to the past, and to the loss of millions of Jewish lives; to thousands of years of history. It is most appropriate that he should be the architect chosen to design the Ground Zero memorial in New York. Daniel Libeskind effectively won this contest because he demonstrated a unique perception for what had to be achieved at ground level rather than, as the majority of contestants revealed, an obsession with vertical architecture. And it has been this reverence for memory that has, as in Berlin, so powerfully charged his architecture. Here the memory is all around, and will never be lost.

John Mack's book, published to accompany the British Museum exhibition, is poignant with regard to the effect of technology on our society and our identity:

It is often said that the invention of writing, and even more so of printing, threatened to dislodge memory from the status it previously occupied in Western culture. It is not only that we dream in pictures and that dredging images from the unconscious works through visual means. We also remember words or texts not through some auditory form of memory but through seeing them as marks on the page.4

The raising of the minutiae in life to the realm of art in the context of memory is best epitomised by Marcel Proust's six volume, À la Recherche du Temps Perdu. There, the memory of a moment in daily life triggers associations, and a train of events. In Neil McGregor's words, 'memory is not, however, a static, nostalgic condition, but an active and ongoing dynamic, and museums must respond to its perpetual reverberations. Accommodating and responding to memory is a central, but rarely articulated responsibility of contemporary cultural institutions'.5

Cross-cultural investigation is a difficult pursuit yet the context of the British Museum reduces the hazards or the raison d'être of such an enterprise simply because as a museum, it has its own history, personal and public associations and responsibilities. Variety in this context is the essence of its being. From this starting point, John Mack, curator and author of the book that accompanies the exhibition, Keeper of Ethnography in the British Museum and Visiting Professor in the Anthropology Department of University College London, is well placed to present an overview of the collection and this interesting subject. This is a fascinating exhibition and a brilliant and stimulating publication. Mack issues a salutary warning on the impact of electronic records and the disintegration of the fundamental need for esteemed figures in culture with the implicit dangers of relegating them to a merely ornamental or redundant role.

Founded in 1753, the British Museum has a collection of humanly created objects and artefacts, unmatched anywhere in the world. The collection spans all periods of history, encompasses all cultures, is housed in a single building and is accessible seven days a week. While this exhibition presents an intellectually challenging range of ideas from different cultures, it also celebrates the position of museum in society, per se. It prompts one also to examine the Enlightenment – the visions of the Museum's founders and the ethos behind such an institution. The notion of how the Museum itself becomes a site, or a 'theatre' of memory is central to the exhibition.

The theme of memory is thus central to the anniversary events of an institution like the British Museum, to the proper study of the objects in its care, and beyond that to the nature of our common human existence. To raise questions such as these is one of the central justifications for the existence of universal collections, for understanding what occurs across and between cultures is fundamental to reassessing and more completely understanding what we are.6

The exhibition is an ambitious one. It begins with an examination of the aide-mémoire produced in different cultures. Nigerian artist Osi Audu has spoken of creating objects as containers of memory. His Monoprint ('Juju'), 1998, evokes the Yoruba conceptions of the inner head, in a structure made from graphite, safety pins, wool and plaited hair. The artist explains his sources of inspiration:

Part of the process of remembering usually involves the installation of a shrine to the inner head (ie Juju) in the corner of the room of the house. It is believed that the memory of the agreement reached with Olorun (God) is locked within the ori-inu (inner head). Installing a Juju in the house is a means of attuning with the memory of the original agreement with God in order to ensure that destiny is achieved. This was the inspiration behind my making of the Juju work.7

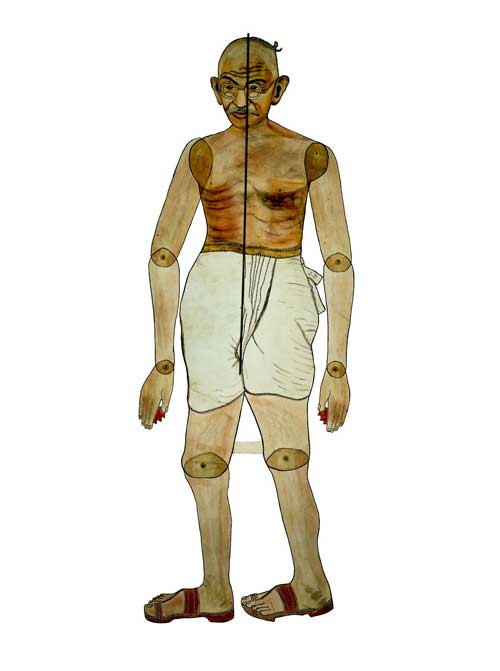

The 'Aide-Mémoire' section of the exhibition draws on a wide range of objects from the Nigerian piece described above, to Roman coins and medals, a Japanese scroll (of the Edo period) of turtles, which is an iconographic reference of longevity, and a Roman version (2nd century AD), of a marble portrait of Greek dramatist Euripides (c484-406 BC). Also classified as an aide-mémoire is the Micronesian stick and shell navigation device, made by mariners in the late 19th century. Objects range from the early 17th century carvings from the Congo, 19th century Maori carvings from New Zealand, and elaborate medieval calendars, including, 'more pictorial, so-called pauper's almanacs for the illiterate'.8

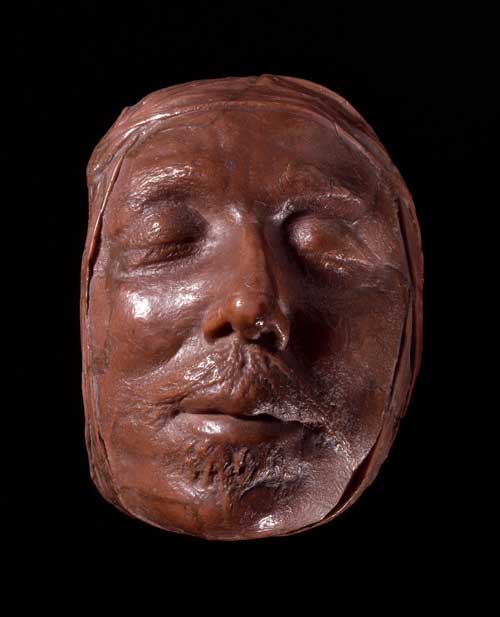

'Living Memory' explores portraiture and medals:

Portraiture is one of the most ubiquitous vehicles of memory. Indeed memory is so interwoven with the topic that, even if the image was not meant in the first instance to be created as remembrance, it may subsequently be judged according to its ability to encapsulate likeness and imbue it with something of the 'soul' of the subject.9

Of memorabilia, Mack continues:

It is only when someone dies, and their personal possessions become suffused with the sense of the missing owner, that the object is redefined as memorabilia. The gallery full of shoes at the Holocaust Museum in Washington would have no meaning were it not for the stories that it recollects, the absences (and the profoundly shocking reasons for those absences) which it evokes, and, for those who know the extermination camps, the 'warehouses' of hair, artificial limbs and so forth piled up there. It is evocative, even if it is only a copy of an 'original' at Auschwitz.10

In the present context, it is apt to conclude the exhibition (which includes many superb objects that I have not listed or described) should be on the subject of photography. The object that most people claim they would grab if their house were on fire, is their collection of photographs. These are rarely documentary records with implied accuracy or reliability in terms of history, but images of how people want to be remembered. For every framed family photo, there is a bin full of rejects, not just because the light was poor, someone was blinking or the subject's nose looked too big; but for a whole range of criteria. The chosen image gives gloss to the past: it becomes an acceptable memory and the past becomes attractive. Memory then has already been subjected to interpretation, even censored.

The photograph may freeze time, but once it becomes a subject of reflection it melts back into the flow of remembered events. It has been a consistent theme of this book that objects stir recollection, that they inspire stories whose retelling constitutes memory. As memory itself is constantly on the move, so too are the narratives, in which the meaning of objects is embedded, forever evolving, reshaped in order to make our sense of the present lead coherently towards a desired future. Photographs too cannot escape this inevitability. The museum of the memory is not a static place, but a gallery under constant refurbishment.11

Footnotes

1. Neil MacGregor, "Preface", The Museum of the Mind: Art and Memory in World Cultures, by John Mack, The British Museum Press, London, 2003, p.8.

2. John Mack, ibid, p.26.

3. ibid, p.26.

4. ibid, p.38.

5. MacGregor, ibid, p.9.

6. ibid, p.9.

7. Mack, ibid, p.25.

8. ibid, p.46.

9. ibid, p.54.

10. ibid, p.54.

11. ibid, p.149.

Dr Janet Mckenzie