by ANGERIA RIGAMONTI di CUTÒ

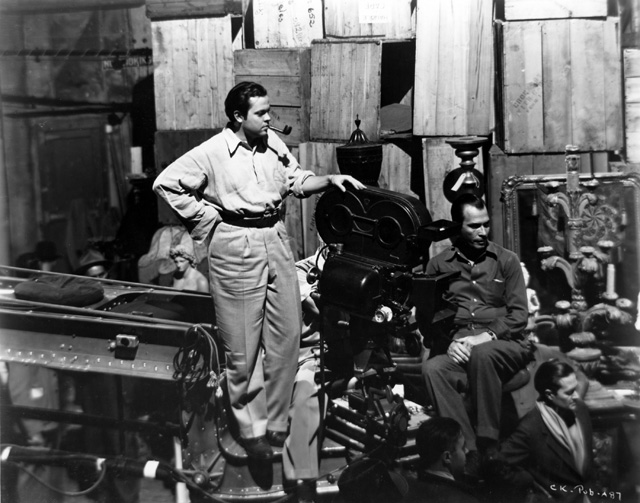

Persistently, and justifiably, judged one of the supreme directors of cinema history, Orson Welles pronounced directing to be “the most overrated job in the world … the only profession where you can be utterly and truly incompetent and go on being successful for 30 years without anyone discovering you” (Paris interview, 1960). Welles was, of course, much more than a director, and esteemed, to varying degrees, as a writer, actor, magician, radio broadcaster, theatrical producer, raconteur and, long before the term was debased, celebrity. Two recent projects, a speculative documentary and a book, consider Welles the graphic artist. These works supplement the recent completion, decades after Welles’s death, of one of his quasi-mythical unfinished projects, The Other Side of the Wind, as well as the even better film about the film, Morgan Neville’s They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead.

Taking as its starting point an abundant stash of drawings, paintings and doodles produced since Welles’s famously precocious boyhood, critic Mark Cousins’s film, The Eyes of Orson Welles, is constructed as a letter from Cousins to Welles, in a form that might be described as “unapologetically” personal. To call it self-indulgent would be an understatement.

[image2]

Cousins, who has used the imaginary conversation device in other films, here adopts a plaintive tone as he combines musings on Welles’s life and work with some observant formal analysis of the drawings vis-à-vis the films, detecting connections and leitmotifs, such as the cinematic nets and grilles that recur in the forceful hatching and shading of the drawings, or the faceless people who coincided with the rise of fascism and absolute power. This graphic and biographical “journey” is articulated through a series of themes, such as chivalry, aspects of kingship and Welles’s (glossed over) love life.

Cousins also rightly draws attention to Welles the social progressive, who, aged 20 (it is still hard not to marvel at his precociousness), staged an all-black “voodoo” production of Macbeth, the opening night of which attracted a fervid crowd of 10,000 in a climate of ruthless segregation. Welles’s support for social equality was not just an abstract ideal, but part of his working practice and lived experience, from the Harlem Macbeth and championing of black jazz musicians to a persistent correspondence with political representatives to tackle antisemitism. A charged incident Cousins refers to is the beating (until permanently blinded) of the black second world war veteran Isaac Woodard by a South Carolina policeman, who was ultimately acquitted by an all-white jury. Plus ça change. Welles closely followed this heinous episode, addressing it in radio broadcasts and in his short but succulent 1955 BBC television series, Sketchbook of Orson Welles, a work that shows off his magisterial talent for intimately addressing an unseen audience.

Welles’s political engagement co-existed with a nostalgic vein, not to be confused with a traditional one: “Most tradition is just a succession of bad habits.” (Paris interview, 1960) A fondness for certain qualities associated with the past are most obviously present in his most cherished projects, the tragicomic Chimes at Midnightand Don Quixote, films that Cousins includes in the category of chivalry. Writing to his friend and producer Alessandro Tasca, Welles’s impressively detailed considerations of how the drawn and photographic images of Don Quixote were to be fused are revealing of some of his knowledge and ideas about visual art and more. Intent on capturing the style of Gustave Doré, who had produced a sequence of Quixote engravings in the 1860s, as well as a smaller, less detailed series of drawings, Welles wrote: “Our first task is to find somebody with a real talent for art forgery.”1 But rather than emulating “all of the shading tricks of the engraver’s art” (present in Doré’s more lavish drawings), Welles wanted the more linear, off-the-cuff dash of the smaller illustrations.

[image5]

He was notably fascinated by forgery and feints, and the human foibles that motivated them, having skittishly played with the theme in his cinematic essay F For Fake. The film still has a lot to say about the art establishment and its so-called experts (“Elmyr makes fools of the experts – who’s the faker?”). For the critic André Bazin, Welles possessed “a genius for bluffing, which he regards as one of the fine arts, in the same league as conjuring, theatre or cinema”.2 Apropos of forgery, the soundtrack of Cousins’s film is punctuated with extracts of Tomaso Albinoni’s mellifluous “baroque” Adagio, a piece that Welles had used in The Trial, and probably a hoax composed in the 1950s by Albinoni’s biographer. And perhaps all the better for it in the Wellesian scheme of things.

Among visual patterns that emerge in the films and drawings, Cousins notes a penchant for oppressively looming perspectives. He links these to the skyscrapers seen during Welles’s youthful stint at the Art Institute of Chicago, but it’s worth considering possible artistic or theatrical sources for that distinctive viewpoint. Welles was known to have admired the theatrical polymath Edward Gordon Craig, whose sets were characterised by towering vertical masses, in turn likely to have been suggested by his mentor James Pryde, a painter of tenebrous, lofty interiors. Craig also, incidentally, asserted the importance of the director over the actor, the latter to be replaced by an über-marionette, and considered the theatrical set an actual protagonist of the dramatic experience rather than its mere setting, attitudes that resound in Welles’s film-making.

One of Cousins’s best visual choices is the repeated interposition of a photograph of an unusually au naturel, wide-eyed and guileless Welles beholding the spectator. But while faux neutrality or froideur are not prerequisites in biography and criticism, Cousins’s film becomes almost unbearable when he indulges in a histrionic questioning of his subject (“Did you damn yourself, Orson, and, if so, for what?” “Were you in a hurry to get old, Orson? Did your youth bore you?”), relentlessly ending his observations to Welles with a mournful and would-be affirmatory “didn’t you?”. This mawkish extravagance culminates in the conceit of “Welles” answering Cousins in a monologue that is excruciating not only for its implausible content, but also for its dire execution in a generically lugubrious rumble that bears no resemblance to Welles’s real voice.

Simon Braund’s book, Orson Welles Portfolio: Sketches and Drawings from the Welles Estate, fortunately includes a project not explored in Cousins’s film, the breezy vignettes for Everybody’s Shakespeare, a series of books about the reading and staging of three Shakespeare plays, aimed at students and teachers and conceived by Welles’s beloved teacher, Roger “Skipper” Hill. Produced when Welles was a mere teenager, these are among his most winning drawings, his graphic timeline of Shakespeare’s life and work in particular is a compelling demonstration that drawing can be simultaneously instructional and captivating. In a letter to Hill, Welles persuasively, precociously and modestly explained his misgivings about his contributions that encompassed youthfully febrile staging directions, pithy character studies, costume notes and even thoughts on hairdressing:

“You’ll find grotesqueries in my stage directions, repetitions and misfirings … The mere presence of Shakespeare’s script worries me. What right have I to give credulous and believing innocents an inflection for his mighty lines? Who am I to say that this one is ‘tender’ and this one is said ‘angrily’ and this ‘with a smile’? There are as many interpretations for characters in Caesar as there are in God’s spacious firmament. What nerve I have to pick out one of them and cram it down any child’s throat, coloring, perhaps permanently, his whole conception of the play? I wish to high heaven you were here to reassure me.”

The Everybody’s Shakespeare drawings also illustrate a key aspect of Welles, namely a pedagogical bent that co-existed with his magus-like persona.

Some of Welles’s drawings were like storyboards, others more like illustrated scripts and letters. Crucially, it is often the amalgamation of text and image that yields enchantment. The doleful, cartoon-like Broadway Blues economically records Welles’s (it turned out) lifelong struggle to obtain financing: “Budget?” “Where does the money go to?” Sent to his father-figure “Dadda” Bernstein, these vignettes also offer flashes of a touchingly filial Welles (probably the most improbable role with which one associates a man who seemed to emerge into the world fully formed) who signed off: “Your lonesome, tired, wet and loving Poobles”.

A self-portrait with a cigar-smoking Kermit the Frog is a small gem and another self-representation illustrating Welles’s spell at the BBC is striking in that it seems formed entirely, and suitably, of electric currents. Striking a darker note is a rare instance of abstraction in an understandably angry-looking work made after Welles was banished from Touch of Evil by studio executives.

Of the more obviously important drawings, those for Faustus are Welles’s most intricate. This production was one of four plays he produced for the Federal Theatre Project, the New Deal initiative aimed at revivifying the theatrical slump of the Great Depression (another was the “voodoo” Macbeth). If the Faustus drawings are the most detailed, they lack the é lan of the costume designs for Chimes at Midnight, which are all reproduced in the book.

While brief texts accompanying different sections are informative, the book would have benefited from a more systematic overview of Welles’s artwork, perhaps in the form of an essay, as well as a bibliography and index, and a clear indication that some of these works are in public archives, most notably at the University of Michigan, which houses the most extensive compendium of Wellesian material.

While both these projects explore Welles as a graphic artist, the suggestion that he was above all a visual artist (“thinking in lines and shapes,” as Cousins proposes) is probably flawed. Welles rejected the received notion that in film the visual is paramount and articulated this belief forcefully: “I know that in theory the word is secondary in cinema, but the secret of my work is that everything is based on the word. I always begin with the dialogue. And I do not understand how one dares to write action before dialogue. I must begin with what the characters say. I must know what they say before seeing them do what they do.” In a 1950 interview, Welles claimed it was the critics who had inflated the importance of image in film when words and story should be the driving force. At the same time, the fact that Welles produced sketches for his radio productions is revealing. With less of an ostensible raison d’être in a non-visual medium, these sketches suggest that, for Welles, drawing might have at least been what the great cartoonist Saul Steinberg defined “a way of reasoning on paper”.

Projects such as these are a reminder that Welles’s complicated oeuvre and its ever-expanding historiography3 continue to generate an afterlife that, fortunately, renews the enduring enchantment.

• The Eyes of Orson Welles (2018), written and directed by Mark Cousins, was produced by Dogwoof Productions.

• Orson Welles Portfolio: Sketches and Drawings from the Welles Estate, by Simon Braund, is published by Titan books, 2019.

References

1. Orson Welles – Alessandro Tasca di Cutò Papers (1947-1995), University of Michigan Library.

2. Quoted in Orson Welles, Volume 3: One-Man Band by Simon Callow, Published by Jonathan Cape, 2015.

3. Among the better biographical and critical works in the vast Welles bibliography are studies by Alberto Anile, Peter Bogdanovich, Simon Callow, Joseph McBride, James Naremore, Jonathan Rosenbaum, François Thomas & Jean-Pierre Berthomé.