by JANET McKENZIE

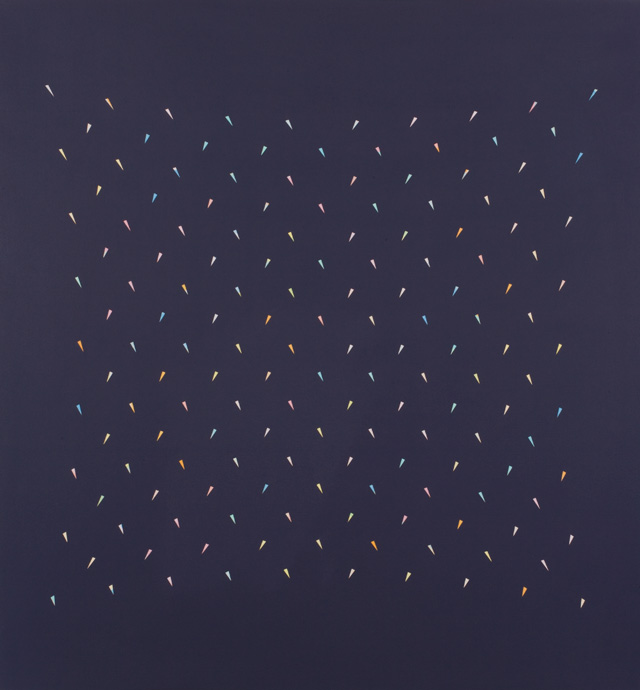

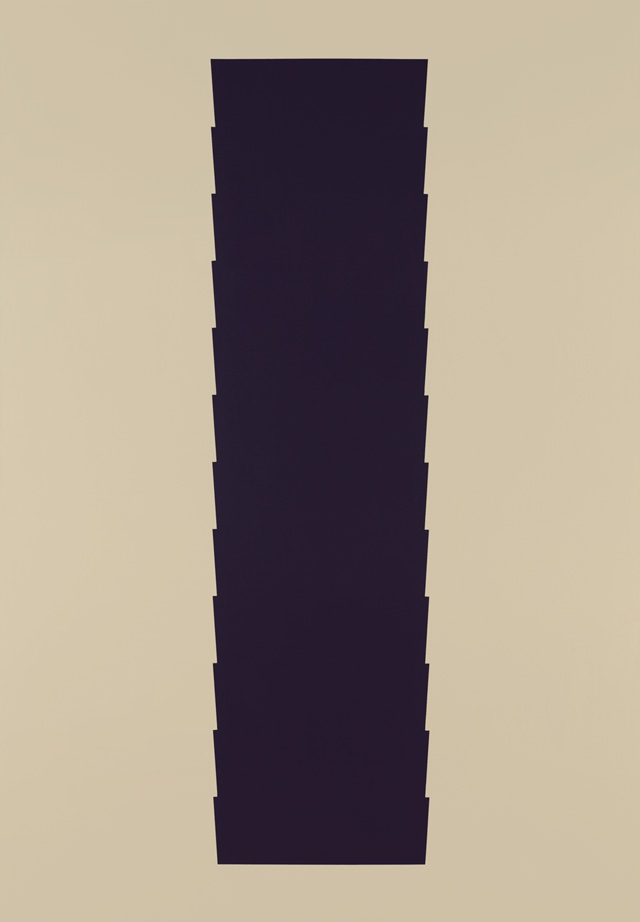

Tess Jaray was born in Vienna in 1937 and came to England with her parents the following year. She trained at St Martin’s School of Art and then at the Slade, returning to the latter in 1968, where she ran the postgraduate programme for more than 30 years. Her abstract and minimal works are distinctive, occupying a rare position in British art. Influenced in the 1950s by American abstract art, her work was given a profound direction on her first trip to Italy by the architecture and painting there. Architecture provided Jaray with a context in which to explore the formal aspects of space; the intellectual atmosphere of her upbringing – especially literature, philosophy and music – had already established the need to visualise abstract thought. A friendship with the writer WG Sebald led to a collaborative body of work of rare sensibility, his poetry and her minimalist paintings and screenprints.

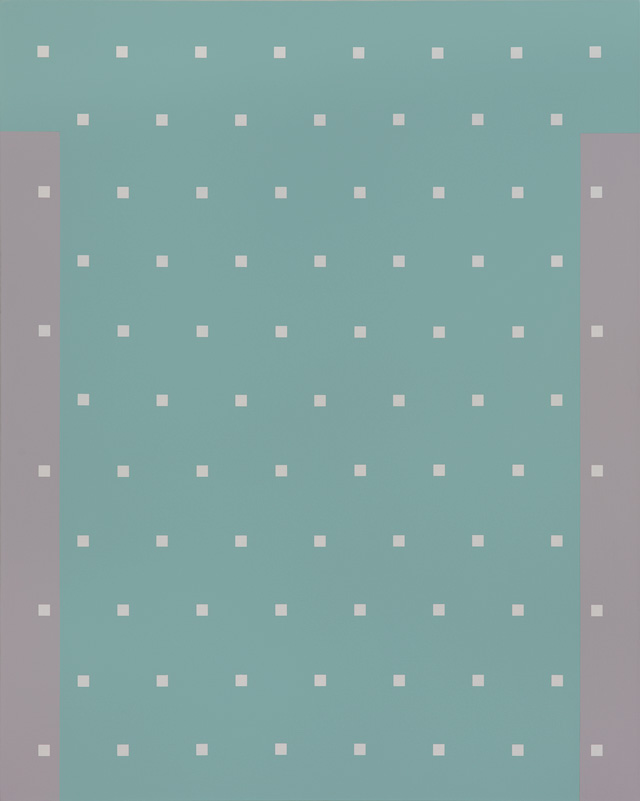

[image3]

Teaching extended Jaray’s intellectual curiosity and she developed a rare gift both to nurture talent and to shed light on the meaning of art. In writing, she is mindful that paintings will not always be better understood through verbal description: “Paintings cannot be explained. But they can be spoken about and circled around, and sometimes those circles can get closer and closer. It seems rather strange – if not unhinged – behaviour to spend one’s life doing something that can’t really be understood.” Jaray seeks “to make sense of the obsessive searching for patterns and repetition in nature and in art that have been so important … They may be seen as a meeting point, a coming together of the head and the heart and the external and the internal. It is not a search for the kind of absolute that some people search for in extremes of nature, like the arctic or the desert. Nor is it that solitude, or isolation, or whatever it is, that those who retreat to monasteries or nunneries are seeking. It is rather a need for the merging of inside and outside, distance or closeness, a marriage, a completeness of opposites. Something that can really only exist in its own space, which is imagined, that we borrow from time to time, for our own needs.”

Her collection of essays Painting: Mysteries and Confessions (2010) combines formal discussion of art and artists and biography with anecdote and humour. The Blue Cupboard: Inspirations and Recollections began as a memoir of her mother and grew into recollections of a postwar childhood in Worcestershire. Franz and Pauli Jaray bought the 18th-century blue cupboard while on their honeymoon in Salzburg. In 1938, they fled their home in Vienna to begin a new life in Worcestershire; the rest of their family perished in Nazi camps. The cupboard is thus a vessel of memory and meaning, endowed with personal recollection and cultural significance, an object that now bears testament to social change in the shadow of political turmoil and the lost world of intellectual ferment in Vienna. It is an object that accompanied the Jarays’ family life as Jewish émigrés to England and can be seen to embody the quotidian rituals, symbolic of feminine roles of continuity in the face of destruction. The eulogy to her mother in The Blue Cupboard weaves aspects of art and life, originally espoused views on abstraction and architecture, daily tasks. The forensic intellectual approach Jaray employs is in itself life-enhancing.

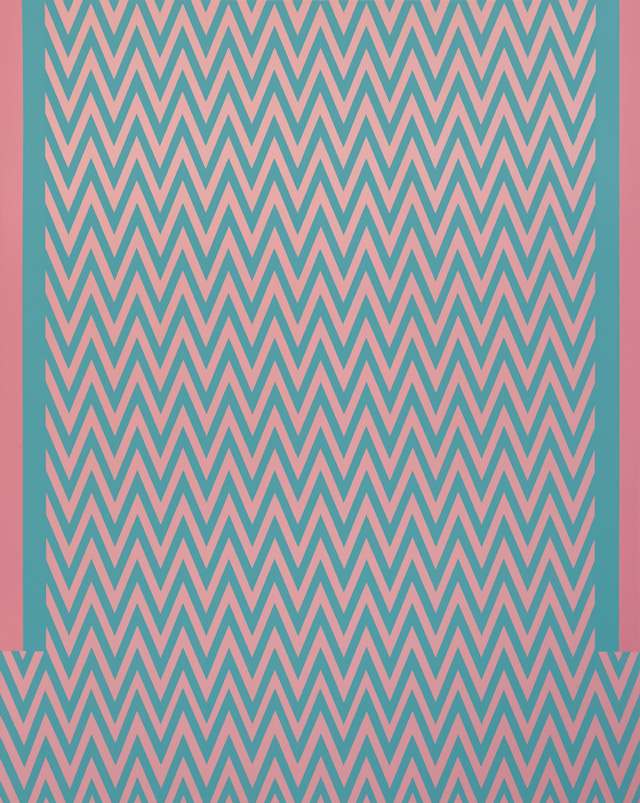

[image5]

Jaray is a painter and printmaker. Her work is many public collections, including the Tate and the British Museum, and, St Mary's Church, Nottingham, and the forecourt at Victoria station in London. In 1995, she was made an honorary fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects for her public art projects, and in 2010 was made a Royal Academician.

Janet McKenzie: As a student, you took art very seriously and believed that to be an artist was the noblest way of life you could choose. How has that changed?

Tess Jaray: This is a very difficult question and impossible to answer in any clear way. I have been painting for more than 60 years and, over such a length of time, the approaches and attitudes to art have always changed, sometimes quite considerably. Many artists over the last hundreds of years have seen their work outmoded or outdistanced during their lifetime. But perhaps it seems to us that the cultural changes over the last few decades have been so radical that they have really changed our perception of very many things, and made it in many ways harder for anyone starting out to become an artist to know how to approach such a route. It is also much harder now for young people to get into art education. I studied art for six years, for which nothing had to be paid. All further education was paid for by the state. Mine was a lucky and very privileged generation. This even extended to the relative ease with which we could find inexpensive workspaces. Now, it’s almost impossible, except for the very wealthy. But art seems to have a way of growing up between the cracks in the pavement, and young artists are now working with very different concepts and aims. Ways of being an artist have massively expanded. Any material can be used as means or subject, which is liberating in many ways. Painting itself is certainly not considered the most important medium, as it was when I was young. This probably makes painting one of the harder routes to making art now but, of course, that just makes it a greater and more interesting challenge.

JMcK: How important was teaching in your creative life?

TJ: I enjoyed it, but I was also lucky to be teaching at the Slade, where the calibre of students has always been very high. At its best, it can mean being involved with, and speaking about, the things that interest you most, and then actually getting paid for it. Since leaving teaching more than 20 years ago, it has become far more demanding and bureaucratic than it was in my time, which is not only sad, but also, in my view, rather unnecessary. But you are obliged, when talking to young artists, to think a bit more carefully than you might do in your studio, so you are learning from their mistakes, which is probably rather unfair. You can develop very close friendships with younger artists if you are facing similar difficulties in your work – or even different difficulties, and several of my closest friends were originally my students. We’ve all been on a similar journey and understand each other in a very special way.

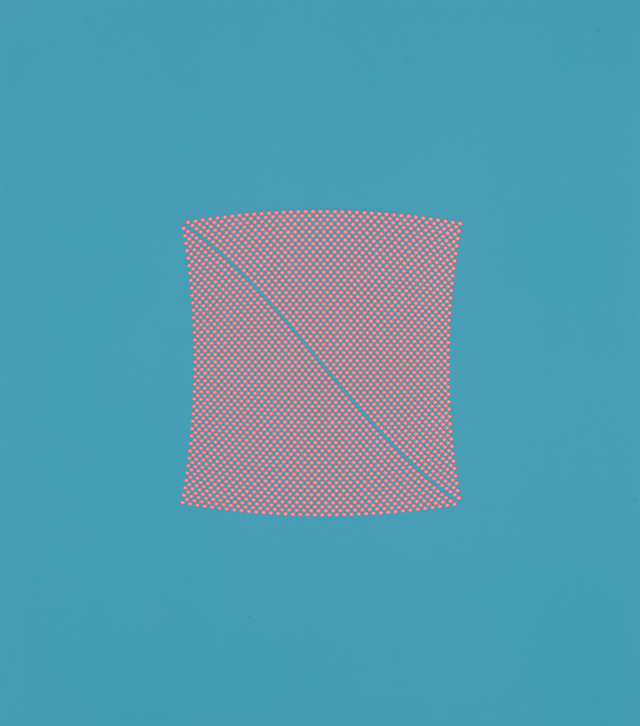

[image7]

JMcK: Abstraction is an essentially American phenomenon. Can you describe the impact of the exhibitions in London in the 1950s and 60s?

TJ: This is a very complicated subject. Many books have been written about the question of who painted the first abstract painting, and many of them contradict each other. I have always accepted the view that Kazimir Malevich and Wassily Kandinsky were the first – think of the influence of Malevich’s Black Square – certainly in Europe and Russia, and I still believe they have had the greatest influence on subsequent abstract work, but I can see that this could be disputed. American artists certainly took on the challenge of abstraction with great force and power, and in many ways made it their own. Abstract expressionism was a hugely influential movement, and artists such as Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock – and others – produced astonishing bodies of work, and abstraction has not been the same since. But there were some before them – Arthur Dove, Georgia O’Keeffe, although she was not, strictly speaking, an entirely abstract painter – who made a real contribution, but have not been so celebrated.

The impact of the exhibitions at the Tate in London in 1956 and 1959 [Modern Art in the United States and The New American Painting] was enormous, followed by wonderful shows of artists such as Franz Kline and the abstract work of Philip Guston, as well as Pollock and Rothko, put on at the Whitechapel Gallery by the brilliant Bryan Robertson. Most art students in London, including myself, started using paint by the gallon instead of small tubes, and a 6ft by 4ft canvas, which up until the late 50s had been considered enormous, became conventional, if not small.

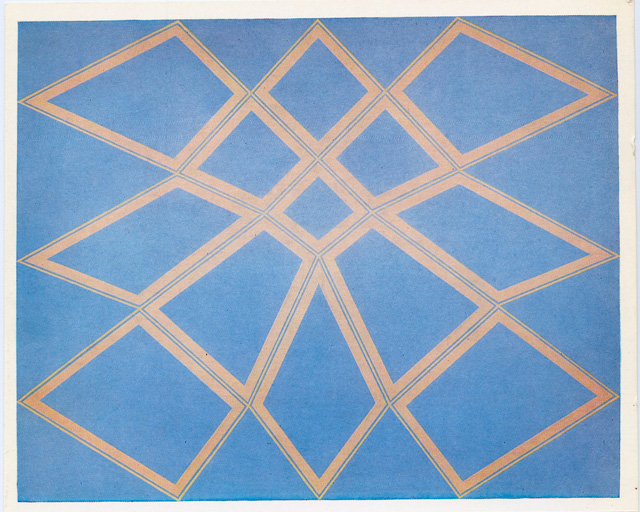

[image8]

JMcK: Italian architecture was a great influence on you as a young artist?

TJ: Huge. But also because it was such a surprise! As students we learned art history at the Slade, and because, at least for one year, we had the famous Ernst Gombrich as a lecturer, we were well informed about Renaissance painting, but no one ever mentioned architecture. I hardly knew what it was. Suddenly seeing, and moving in and around, such great buildings by the likes of Filippo Brunelleschi, Donato Bramante and Leon Battista Alberti was mind-blowing. I didn’t understand what I was seeing, why one should feel so deeply affected by these extraordinary spaces. It took many years before I started to grasp that creating our own space is in many ways how we define ourselves, how we protect ourselves, how we reflect both the world around us and relate our inner selves to that. Even now, I find it hard to really understand the greatness of those architects, and to see that they have never been surpassed. I remember as a small child looking up at cathedral towers and thinking, when I am a grownup I’ll understand how this was done. Well, I never have. But I’m still hopeful, and every mark one makes on a canvas creates some kind of space from which one learns, so perhaps one day …

JMcK: Agnes Martin is the artist who springs to mind when I look at your work, the refinement and distillation of natural form and architecture, sharing parallels with music in its immediacy, its ability to resonate with spiritual experience.

TJ: When I first saw Martin’s work, in the 1960s, I was bowled over. Her work still resonates more powerfully than perhaps any other contemporary artist. It’s something to do with her ability to do so much with so little, without being at all a “minimalist”. It is all those things you say, but in her work the means with which she expresses those things is somehow hidden. In some of her smaller work on paper, for instance, there really aren’t many clues as to why they are different from any squared-up exercise book, other than the touch of the pen or pencil. But they are, of course, and it’s immediately recognisable. It’s something to do with the transference of spirit to the surface, which can’t really be learned, or contrived. It’s there or it isn’t, and that’s one of the mysteries of painting, of art altogether, and one of the reasons we continue to be interested, because we can never get to the end of it all.

[image9]

JMcK: Thinkers and writers such as WG Sebald and George Steiner have enriched our understanding of culture and history immeasurably. I find your writings profound and also funny. Is that a female trait or are you daring greatly in order to shed light on the metaphysical space of visual form with a deep connection to nurturing rituals traditionally performed by women?

TJ: Probably not only thinkers and writers enrich our understanding of things, but anything at all that affects us in some way. When we are touched by the work of writers such as Sebald, and of course many others, it can often be because they articulate feelings and observations that we haven’t been able to quite reach: they do it for us, and bring things into the forefront of our minds that up till then had been hidden. But they can also enlighten us with ideas or images that are completely new to us, but change the way we see things. Our lives are really a progression of such revelations. It’s one of the comforts of getting older, some things do become clearer.

JMcK: Can you describe working with Sebald?

TJ: Yes, it was great.

JMcK: Your work represents a distillation of life and enables reflection and meditation. Yet technological developments of the past 20 years have resulted in us being bombarded by visual forms every day: advertising, television, computers and social media. How do we survive the overwhelming barrage of visual form?

TJ: Artists are not the only ones suffering from this bombardment of all those things. Everyone does. It’s one of the many unanswerable questions of our time. Perhaps people, at least young people, are adapting, and finding new ways of learning how to concentrate.

I don’t follow any social media, and must be one of the few people in the western world not to have a mobile. Presumably I’m missing out on many things, but I couldn’t handle all the interruptions when I’m trying to concentrate on work. I really don’t know how people do it!

[image10]

JMcK: You have made an important distinction between art therapy and catharsis. Can you describe how creativity plays an important role in one’s wellbeing and how solving formal aspects of painting might have parallels with emotional and intellectual processing?

TJ: Wellbeing, sadly, does not depend on creativity. Art used in therapy has probably been very helpful in many cases; I’m not qualified to comment. But one thing I am certain about is that art therapy is not art. What art is no one has yet satisfactorily explained, which may be partly why so many people still want to make it; great art does indeed create a kind of catharsis, but it certainly can’t be intentionally built into the process of making, and it’s probably easier to explain and understand with music than it is in painting.

• Tess Jaray’s work will be on show later this year in East of the West, a two-part solo exhibition. The first part, which includes some of her most recent paintings and a selection of early drawings, will be at Exile, Vienna, from 12 September to 19 October 2019. The second part, which focuses on early painting and contemporary works on paper, will be at the Vienna Contemporary Art Fair from 26-29 September 2019.

.jpg)

,-2017.jpg)