Tate Modern, London

3 July – 27 October 2019

by BETH WILLIAMSON

Panayiotis Vassilakis, known as Takis, (b1925, Athens, Greece) is a self-taught artist. Even though he began by studying ancient sculpture, this was not to hold his attention for too long and, on moving to Paris in 1954, he began investigating the potential of electromagnetism for making sculpture. It was the idea of energy itself that captivated him much less than the “visual qualities” of what he could make. In Paris, London and New York, he became a well-known figure among artists, writers and musicians such as William S Burroughs, Marcel Duchamp, Allen Ginsberg and John Cage.

[image2]

This exhibition at Tate Modern is designed around themes key to Takis’s practice: magnetism and metal, light and darkness, sound and silence. Beyond these three themes, it adds three more that allow it to foreground his engagement with creative and scientific communities throughout Europe and the United States. These themes are: poetry, transmission and space; activism and experimentation; and music of the spheres, more of which below.

[image3]

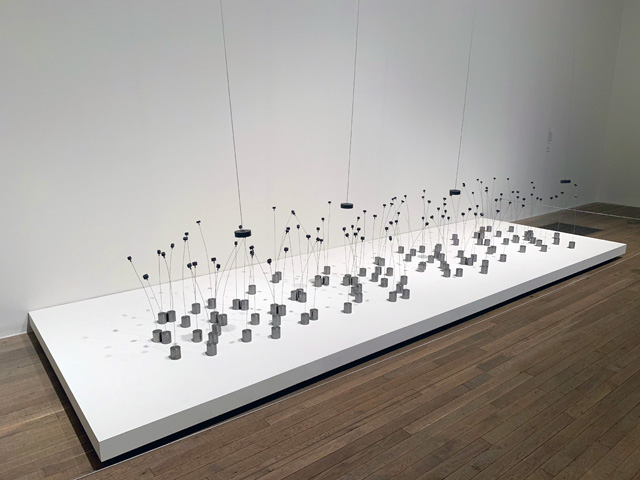

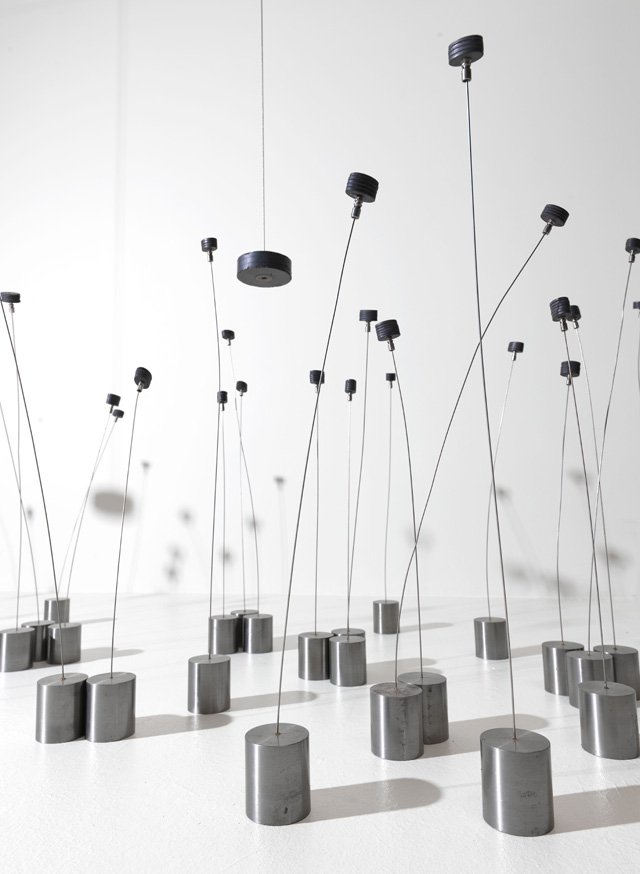

The first section of the exhibition, Magnetism and Metal, is rather underwhelming, perhaps because of the mysterious sounds ahead that demand our attention and lure us away from this first room. It begins, then, with some figurative work by Takis followed by his magnetic sculptures. The swaying flowers of Magnetic Fields (1969) have a curious impact because of their sheer numbers. Other works, such as Magnetic Wall 9 (Red) (1961), are more intriguing, as what is usually grounded and motionless is given lightness and movement. Takis’s purpose with such works is to lift the spectator out of the everyday. As he explains in the exhibition leaflet: “A simple floating nail could be sufficient to liberate a spectator from his ordinary daily task and worries for a few minutes, or even change totally his attitude towards life.”

The next section of the exhibition, Poetry, Transmission and Space, is quite astounding, with images and archival documents relating to the performance Takis staged at Galerie Iris Clert in Paris in 1960. The Impossible – Man in Space featured the poet Sinclair Beiles suspended in mid-air by a system of magnets while reciting his poem Magnetic Manifesto. Around this time, too, Takis often made the journey to London and the gallery Signals London was named after his signal sculptures.

[image14]

Sound and Silence is the third, small, section of the exhibition and feels rather like a sacred space. A bench is positioned in the centre of the gallery facing Musicals (1985-2004), a series of nine wall-mounted panels, each with magnets to pull metal rods against instrumental strings and produce a single note and its reverberations – what Takis called “space sounds”. Listening to Musicals repeat performance over and over again is entirely compelling as a contemplative act.

[image4]

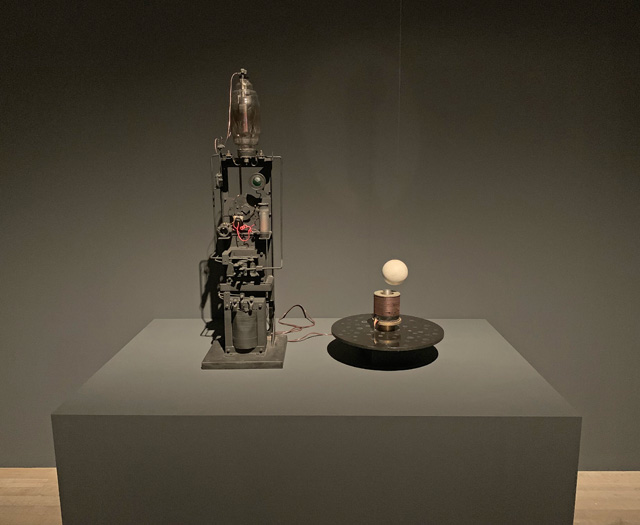

It was in the early 60s that Takis began to use electrical lights in his work. In the exhibition’s Light and Darkness section there is an eerie feel to the ramshackle assemblages of bulbs, wires and machine parts and other objects of various sorts. The atmosphere is that of a scrap-metal yard where disparate objects have been put together in a strange manner. His inspiration for this development, we are told, comes from the station signals he observed during his train journeys from Paris to London. From his childhood in Athens, he recalls just a single traffic light in the main square and the lights of London and Paris were dazzling by comparison.

[image5]

The penultimate gallery, Activism and Experimentation, addresses Takis’s social and political activism. Archival film and other materials tell the story of, among other things, his desire to democratise art through the making of mass–produced editions of his sculptures to be sold cheaply in gallery shops, much like posters, books and postcards are. He saw the connections between art and science as vitally important, too, suggesting: “We try to achieve spiritual collaboration between artist and scientist. Otherwise, the technology is just a gadget.” To that end, in 1968 he was a visiting fellow at the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the US.

[image7]

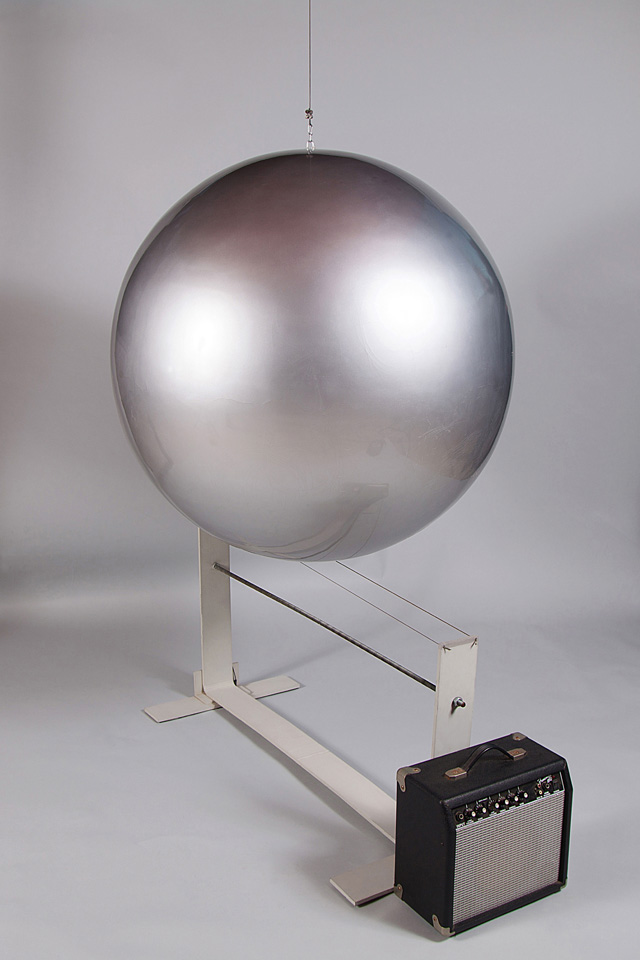

Music of the Spheres is the final, largest and emphatically most glorious space of this Takis exhibition. The whole length of the gallery is filled with insect-like Signals. Negotiating your way around the various groups of works feels slightly precarious and provisional, as there is no single route through. Ultimately, what guides you is the irresistible draw of the Music of the Spheres at the far end of the room, solemnly and meticulously orchestrated by a gloved gallery attendant activating the work periodically and allowing periods of silence in between. The installation here, including Musical Sphere (1985) and with Gong at its centre, is representative of the open-air theatre space at the heart of the Takis Foundation, opened in 1993 and accessible to all.

[image6]

The exhibition space as a whole is at times difficult to navigate not because of a lack of chronology or mapping of themes, but because of the necessarily low lighting levels in some spaces and perhaps the sense of disorientation that results from sound travelling intermittently from one space to another. Yet it is the sounds of this exhibition that stay with me. The reverberating Gong that gradually quietens to silence offers a space for reflection. The single notes of Musicals point to a stripping back or simplification of things. These are helpful prompts for living in frantic times.

• The exhibition will be at the MACBA, Barcelona from 21 November 2019 to 19 April 2020 and at the Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens from 20 May 2020 to 25 October 2020.

-1961.jpg)