Thomas Dane Gallery, London

14 October – 15 November 2014

by HARRY THORNE

Steve McQueen’s Ashes is a portmanteau of old and new, of beauty and brutality. While the two sculptures and the short film – which are currently on show at Thomas Dane Gallery in London – are recent works in many respects, they are also products of centuries of violent histories and untimely deaths.

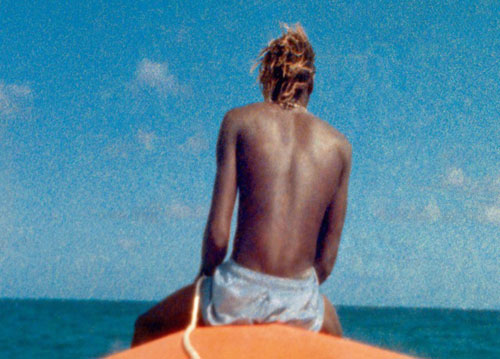

Projected on to a standalone screen, the slender black figure of the eponymous Ashes stands on the foredeck of an orange boat. As the vessel struggles to find a smooth path through cobalt surf, the young man smiles. He sits, he stands, he poses and he falls into the wake. This is a simple image of happiness immortalised by rough Super-8 film. Eyes fixed on the camera, muscles flexed, Ashes is a vision of childish playfulness and arrogance. The legendary cinematographer Robert Müller originally captured him in 2002 when he and McQueen were in Grenada to make Carib’s Leap – a short film memorialising the Carib Indians of 1651 who jumped to their deaths to avoid the control of the conquering French forces – but the footage of Ashes was shelved. While the material depicts a free, youthful vivacity, at that point it was one-dimensional, far from a finished work.

What has elevated these visuals is the overlaying of a more recent soundtrack, recorded in 2013. As the dark figurehead of Ashes continues to play at the front of the boat, two heavy Grenadian accents tell the story of his premature death. Returning to Grenada last year, where his own parents were born, McQueen enquired as to Ashes’ whereabouts. As the young man again turns and smiles at the camera, the answer to McQueen’s question floats across the gallery. The Grenadian locals describe how, one day, Ashes found a parcel of drugs on the island – drugs that he was convinced would make him rich. But as days passed by, men came and found their way to Ashes. The camera pans up from his slender legs to his faded blue shorts and settles on his smiling face. “And then they shoot him in the hand for him to let go of what he was holding,” the voiceover intones. “And when they shoot him in the hand, he let go but he tried to run and then they shoot him in the back and when he fell one of them guys went over to him and shoot him up around his belly and his legs and thing.” Yet again, Ashes falls into the sea. “And that was about it,” he says, leaving nothing to accompany the images but the sound of the boat’s bow repeatedly pressing into the waves.

It is this juxtaposition that makes Ashes so striking. The combination of the mesmerising visuals and the painful voiceover creates an anxious and unavoidable conflict within the viewer. That this affecting area of tension is present at all is a testament to McQueen’s talent as a director. While the footage itself has existed for 12 years, its significance was exposed only at a much later point via the overlaying of the soundtrack. Dave Hickey writes in After the Great Tsunami: “As long as nothing but ‘the beautiful’ is rendered ‘beautifully’, there is no friction, no subversive pleasure, and things do not change.” It was McQueen who chose to shelve the original footage, who saw it as beautiful yet somehow insufficient, just as it was McQueen who married the video with the harrowing story several years later. Without the backstory of Ashes’ murder, there is no friction but simply comfort, and as many of McQueen’s works illustrate, from the early art-films Bear (1993) and Just Above My Head (1996) to the later feature films such as Shame (2011) and 12 Years a Slave (2013), he rarely settles for the comfortable.

Broken Column, a pair of sculptural accompaniments to Ashes, sit within Thomas Dane’s secondary space further up Duke Street. The two black columns lie in adjacent rooms, identical in every way bar their size and presentation – one is more than two metres high and is atop a wooden packing crate; the other, a quarter of the size, stands behind Perspex on a white plinth. Both are built from the same jet-black Zimbabwean granite, both are fragments, struck in half at a midpoint, and both have a resonance of death. The columns cannot, however, be seen as the reification of Ashes’ death alone. There is a doubling present in the sculptural works just as there is in the film. McQueen is centring and paying homage to the many untimely deaths of young, black men both in Grenada and further afield. While the masonry of both the full-size sculpture and the small-scale simulacrum is flawless, each form is also fractured, denied the opportunity to exist as a complete, accomplished form. As we circle the rough cross-sections of the granite obelisks, we might recall the shocked face of the precocious Ashes falling from the boat.

McQueen is an artist who rediscovers and choreographs, playing the part of collagist as he assembles fragments of history. He records, selects, refuses, archives, arranges and composes in order to create a striking composite that generates friction, to borrow Hickey’s phrase once more. He grasps a pre-existing aspect and mechanises it, concealing beneath its outer shell a nexus of comment and questioning. He takes a video of a young Grenadian boy, and converts it into a monument to those countless others who have died premature and unnecessary deaths.