Stefan Brüggemann: Not Black, Not White, Silver, installation view, Mostyn, 2023. Photo © Rob Battersby.

Mostyn, Llandudno

18 March – 17 June 2023

by VERONICA SIMPSON

Walk into the first gallery at Mostyn and you can’t escape the giant chunk of graffiti, suspended from a wire rack, diagonally bisecting the vast white space. It appears initially to be a thin, translucent sheet covered in angry blue, red and black spray-paint squiggles, a thing of effervescent protest, of lightness and spontaneity. But as you get closer, you realise it is entirely made up of polished aluminium tiles, the same tiles on front and back, the same graffiti. Suddenly aware of the enormous heft of these materials, of this backdrop, the words take on a different weight – they transform into indecipherable inscriptions on some strange monument to our times.

This work, Headlines and Last Lines in the Movies (Guernica), 2019, by Stefan Brüggemann (b1975, Mexico City), was last seen hung in the foyer of the Centre Pompidou, Paris, in 2019. It must have looked impressive there, its reflective surfaces constantly animated by the ebb and flow of thousands of people. Here, in the calm of the Mostyn gallery, its presence is quieter, even if the words are jostling for attention.

Stefan Brüggemann: Not Black, Not White, Silver, installation view, Mostyn, 2023. Photo © Rob Battersby.

Once, in the time before street art and smartphones became ubiquitous, seeing spray-painted words on a city wall or building, an act of rebellion, disenfranchisement, was mildly shocking. Now that street artists have been co-opted into the gentrification agenda, their doodles brightening up every blank space in urban areas, from end-of-terrace walls to scruffy hoardings and smelly railway arches, graffiti has lost its edge. The swearwords and tags are now just part of the urban grain.

Stefan Brüggemann. Headlines and Last Lines in the Movies (Guernica), 2019 (detail). Alupanel, aluminium, spray paint, 349 x 777 cm (137 3/8 x 305 7/8 in). Photo © Rob Battersby.

If the logical next step is to deface more expensive, precious materials, that is exactly what Brüggemann has done with the three new works surrounding this shiny mega-mobile. Two substantial slabs of marble bookend the work, one green, the other white with grey streaks. The green one, Eroded Painting (Now White), 2022, features a single spray-painted white word: Now. Beneath it are five lines of text in a regular, albeit fading, black font, which I initially struggle to make out: Eroded Language, Eroded Meaning, Eroded Speech, Eroded Landscape, Eroded Mental Landscape. Staring at its gnarly, defaced surface, it emerges as a rather fitting epitaph – a monument to our fragmenting relationships with words and language.

-2022-11.jpg)

Stefan Brüggemann. Eroded Painting (Now White), 2022. Spray paint and vinyl text on marble, 230 x 150.2 x 4.1 cm (90 1/2 x 59 1/8 x 1 5/8 in). Photo © Rob Battersby.

As the show’s curator and director, Alfredo Cramerotti, tells me: “Once we lived in a world of headlines, but it would be one headline per day. Now there are multiple new headlines, new statements and challenges, every second.”

The opposite work is Eroded Painting (Hot Ice), 2022, and, as the title would indicate, the word Hot is sprayed in red across its cold surface, ICE sprayed in spindly blue capitals below it, and a smeary black word joining this trio at the bottom, World. But what is the meaning here? What is the point? I often struggle with art that relies on text for its impact. Simply presenting words on a page or a wall, at whatever scale, can seem too much like graphics, information or communication.

-4.jpg)

Stefan Brüggemann. Eroded Painting (Hot Ice), 2022. Spray paint on marble, 230 x 150.2 x 4.1 cm (90 1/2 x 59 1/8 x 1 5/8 in). Photo © Rob Battersby.

What makes it art? When the words and the materials and the presentation coalesce in such a way as to cause friction, to provoke a visceral response, to compel us to search our minds for the meaning, that makes it more than the sum of its parts. Graffiti sprayed on expensively excavated marble definitely has shock value. The words themselves on the first work – contrasting the solemnity of marble and conjuring a funereal ode to the value of language, along with the bold temporal instruction NOW – definitely resonate. I am not sure that Hot Ice World says as much, though.

-2022-12.jpg)

Stefan Brüggemann. Eroded Painting (Amazon), 2022. Gold leaf, vinyl text and spray paint on canvas, 160 x 230 x 4 cm (63 x 90 1/2 x 1 5/8 in). Photo © Rob Battersby.

There is something interesting going on, however, with the third wall panel in the room, Eroded Painting (Amazon), 2022, in which a large expanse of gold leaf is laid out across a huge canvas, the leaf squares curling and fraying scruffily around the edges. Across the centre of this precious material, the word AMAZON is emblazoned, freehand graffiti-style, in red and blue paint. Overlaying this is the same Eroded “ode” that appeared on the first Eroded Painting (Now White), but here there are two of them. What is this saying about the Amazon, or Amazon? It works both ways, whether referencing the soil erosion in the vast Amazon jungle caused by industrial-scale illegal logging, or the online-shopping megabrand, whose role in giving easy access to books, printed and audio, and a limitless array of TV and movies has resulted in the proliferation of words to a point beyond saturation. The speed of their acquisition has probably eroded the value of any of them individually – turning what were once significant, treasured events, objects or experiences into disposable, instantaneous elements in our lives.

Cramerotti explains: “It’s less about graffiti itself and more about language and typology, and how we shape our lives through language and how it can be articulated in different forms.” As he says in the introductory panel: “[Brüggemann’s] art pieces create doubt and invite audiences to consider and take up a position. The text becomes temporal and collaborative, the works in the exhibition are observations to be completed by an engagement with the spectator.”

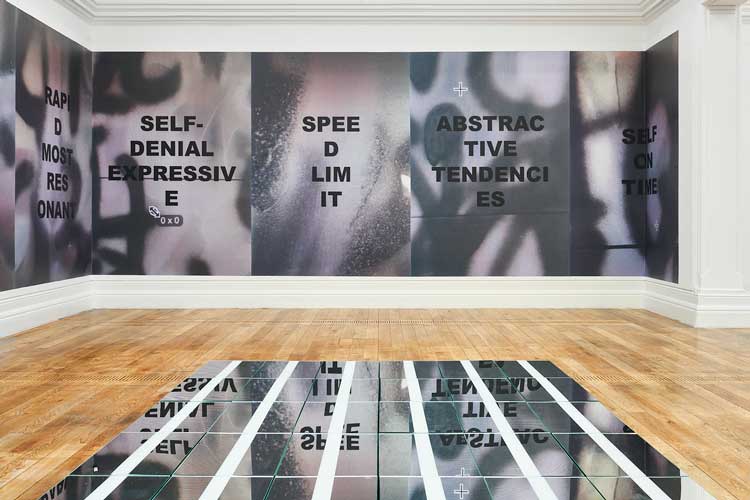

Stefan Brüggemann. Foreground: Mirror Boxes, 2016. Background: Hi-Speed Contrast, 2018. Poster paper, site-specific installation 10 parts, each 279.1 x 203 cm. Photo © Rob Battersby.

It is an uneasy collaboration, at times. I blow hot and cold in my reaction to the work. I am underwhelmed, for example, by the huge posters of smartphone screenshots plastering the walls of the second gallery (Hi-Speed Contrast, 2018), with fragments of text, words bisected and rearranged on top of each other, but not in such a way as to say anything new. These seem more like graphic posters than art. “All – Ow- Act- Ion,” reads one. “Self- Denial – Immersiv-E,” reads another. But I do like the way they contrast with the physical, material presence of the Mirror Boxes (2016) sculpture that commands attention in the room’s centre. These seem innocent, like shiny, tiny, kitsch coffee tables clustered in formation, except for the word Trash scratched faintly but legibly across each side.

In the next gallery, a pile of broken neon words is gathered in the centre of another, large mirror box (This Work Is Realised When It Is Destroyed, 2014). It is impossible to work out what they might once have spelled, but we can admire this little totemic mound, these shards of words, of glass, while distracted by the reflections on the cube’s surface of our feet, our bodies and the room around us.

-33.jpg)

Stefan Brüggemann. I Can’t Explain and I Won’t Even Try, 2003. Red neon, edition of 3, 253 x 88 cm (99 5/8 x 34 5/8 in). Photo © Rob Battersby.

A perky, red neon statement of unbroken letters glows on the wall opposite: I Can’t Explain and I Won’t Even Try (2003). Eerily, this is a phrase we also hear, emanating in Iggy Pop’s rasping, growl, from behind the huge painting that straddles the two far corners. Hyper Palimpsest (2019) was first shown at Hauser & Wirth, along with this recorded text: Iggy Pop Reads Text Pieces (Hyper-Palimpsest), 2019. A 15-minute monologue from the lithe but weathered rock star reading Brüggemann’s entire text statements, like a catalogue, it escalates from grumpy mumblings to a rage-filled rant. It was Brüggemann and Cramerotti’s idea to have the sound piece emanate from behind the painting, as if voiced by some angry gremlin. In its scale, its inky blackness, the hints of angry words that peep out from its layers of murk, this work speaks of some of the worst aspects of our disembodied, dissociated, reactive, bile-drenched, social media-inspired verbal outpourings.

-31.jpg)

Stefan Brüggemann. Hyper-Palimpsest, 2019. Acrylic and spray paint on wood, 16 panels, each: 205 x 120 x 5.5 cm (80 3/4 x 47 1/4 x 2 1/8 in). Overall: 410 x 960 x 5.5 cm (161 3/8 x 378 x 2 1/8 in). Photo © Rob Battersby.

Cramerotti says there was a lot of dialogue about which works would go in the show – spanning 20 years of Brüggemann’s practice – as well as where it would go. “It was more a process of editing,” he says. He wanted to celebrate the diversity and breadth of Brüggemann’s work, across film and video (there are two cute, but hardly profound video works), sound, sculpture, painting and wallpaper. And this has been skilfully done, making the most of these bold, contemporary galleries within Mostyn’s Victorian shell. Cramerotti likens Brüggemann to Bruce Nauman in his versatility. But Nauman puts so much of himself into his work, and I feel this may be what is missing, for me, in Brüggemann’s work. He is too distanced, too ironic, too removed from the subject. We need to be drawn into the visceral nature of how he feels, perhaps, for its full power to materialise.