Design Museum, London

26 April – 15 December 2019

by ROSANNA MCLAUGHLIN

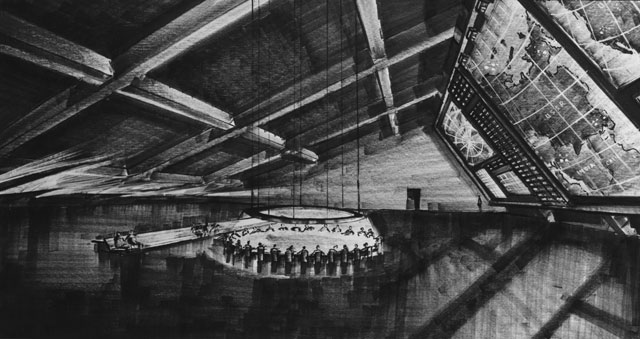

The first object I lay eyes on at Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition, at the Design Museum, London is a director’s chair: lengths of faded mint canvas slung across an old wooden frame, the name “Kubrick” stencilled on to the side in paint. Nearby are an Academy Award, a favourite chessboard (no mythology of the genius auteur would be complete without one) and a stack of black leather trunks with silver studs, used to haul film kit around. In addition to familiar tropes of cinema hagiography are examples of a more niche variety of nerdiness. “Stanley Kubrick searched for the perfect box to store his growing archive,” explains a curatorial note, placed on a stack of nondescript A4 cardboard files – presumably the director’s favoured storage solution. This is an exhibition for the fan club, I think, for the already converted. Who else would give a toss about a man being fussy about stationery?

[image3]

I am not part of the fan club, and I realise at the opening of the exhibition that this places me in the minority. Don’t get me wrong, I am no Kubrick hater. I enjoy perusing the original sketches for the maze garden in The Shining (1980), the notes for the running order of the battle scenes in Spartacus (1960), and the revelation that the visual register of Full Metal Jacket (1986) was inspired by the Vietnam war reportage of the photographer Don McCullin. I can appreciate the significance of Kubrick’s oeuvre, the extent of his influence and the doggedness of his vision. All the same, I find it odd that anyone would want to buy a cup bearing the logo from A Clockwork Orange (1971), or pose for selfies in front of the car that the film’s protagonist drives on his way to rape a woman who later kills herself as a consequence.

[image2]

For my part, where Kubrick’s films succeed is when they make crystal clear the pact between male brutality, sexual permission and counter-cultural cool in the 20th century. A friend of mine, a film buff, explained that Kubrick wanted to shake his audiences from the comfort of their cinema seats: subjecting them to visual abuse, rather than allowing them to get their kicks from it. Judging by the abundance of smiling fan boys at the opening, it would seem that, in this respect, he failed.

[image5]

The exhibition is divided into sections that represent Kubrick’s key films. Among the posters and polite letters between Kubrick and Hollywood stars are a number of items that show what it was that made the director so popular: his eye for the spectacle of controversy. This is a quality most baldly apparent in the 1962 film Lolita, based on Vladimir Nabokov’s novel about the sexual relationship between a 12-year-old girl and her middle-aged stepfather, Humbert Humbert. Nabokov first released the book in 1955 through Olympia Press, a publisher of erotic fiction. It went on to become a best-seller, the first book since Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind to sell 100,000 copies within three weeks.

[image8]

The Lolita section of the exhibition is painted pink – presumably for young girlhood – and there is a provocative quote from Kubrick on the wall. “If I could do the film over again,” it reads, “I would stress the erotic component of their relationship with the same weight Nabokov did.” Kubrick filtered out the explicit sexual details of the book, replacing them with a weird, slapstick element, in the form of Peter Sellers, who plays Clare Quilty – Humbert’s rival for the young girl’s affection. Arguably, this makes the film more sordid, turning a tale of sexual abuse into something approaching a kooky comedy.

Lolita was always going to be a controversial film to produce. On display are complaints from church groups about the film’s sexual subject matter, along with Kubrick’s responses. “Dear Sir, We understand that you are to produce a film based upon the book Lolita,” reads a letter from Canon L John Collins of Christian Action in 1961. “We believe that any such a film must have [a] deleterious effect upon our society, particularly in the light of the publicity already given to the book Lolita, and therefore ought not to be made.” In his reply, Kubrick feigns innocence. “The air of sensationalism which has surrounded Lolita from the beginning has been completely beyond our control, and we have done everything possible to avoid it and detach ourselves from its implications,” he writes. His argument is entirely undermined by the publicity campaign that surrounded the film’s release. At the Design Museum are photoshoots of Sue Lyon, the 14-year-old actor cast in the lead role, suggestively licking a lollipop, along with the official poster that plays up to the debate over censorship and propriety with the line: “How did they ever make a movie of Lolita?”

[image4]

Outcry also followed the release of A Clockwork Orange – a fantasy of dick-slinging, wanton violence based on the 1962 novel by Anthony Burgess. At the Design Museum are a mixture of original and reproduction props, including the costumes worn by the protagonist Alex and his “droogs” – a gang of young men who speak their own private language, whose absurd and smutty comportment is part Shakespearean mechanical and part schoolboy speaking pig Latin. They wear codpieces over their trousers, maraud around brutalist estates beating up vagrants and rape women for kicks. Kubrick presents the violence in A Clockwork Orange in the style of a Broadway musical. The droogs wield metal chains and batons with balletic grace, and tap dance their way through sexual assaults.

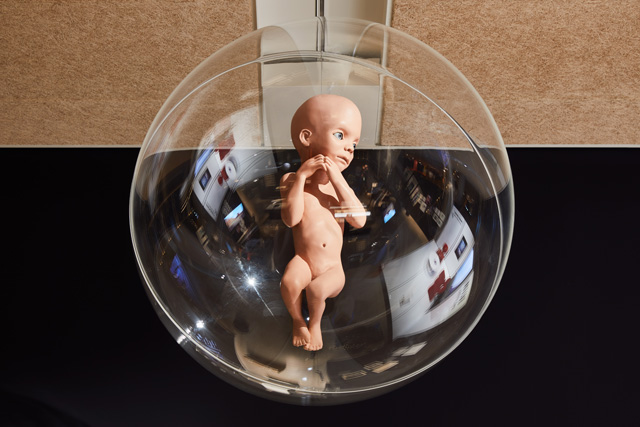

I watch part of A Clockwork Orange in a screening room at the museum, and notice how intensely homosocial it is: a group of horny youths bonding over group sex and violence. Women are either ridiculous mothers or fuckable props, objects to facilitate their rituals. Among the paraphernalia on show are the mannequins of female bodies that populate the Korova Milk Bar, the droogs’ hangout. The set was inspired by the artwork of Allen Jones – an artist best known for making hat stands, tables and chairs out of female sex dolls. At the Korova Milk Bar, the mannequins are used as tables and drinks dispensers. Pull a lever between the legs and fill up a glass from the nipples. Also on show is a giant, shiny white penis, the object with which Alex taunts a woman and then kills her by shoving it down her throat.

[image6]

Kubrick’s flirtation with abuse has seen him hailed as “taboo-breaking” and “uncompromising”. According to Malcolm McDowell, the actor who played Alex, he was also something of a shark. In a recent interview with the Guardian, McDowell revealed how Kubrick had cheated him out of his share of the film’s royalties. “It was a terrible way to treat me after I’d given so much of myself, but I got over it,” McDowell reflected. “Doing this film has put me in movie history. Every new generation rediscovers it – not because of the violence, which is old hat compared to today, but the psychological violence. That debate, about a man’s freedom of choice, is still current.” A man’s freedom of choice is about right: women do not get much of a look in.

On my return home from the exhibition, I rewatch Lolita, and wonder what it was like for the girl cast in the role of Nabokov’s “nymphette”. Lyon was a child when her image was plastered on billboards and magazine spreads, the objectified centrepiece of a mid-century battle between church and cinema played out by men. Perhaps the most haunting document on show in the exhibition was a letter written by Lyon to Kubrick in 1994, after the two had evidently lost touch. “My dearest Stanley,” she writes, “This won’t be a long letter since I don’t know if it will reach you or not. Where to begin? Well, I don’t use the name Sue Lyon any more. I’ve been happily married for the past 10 years, and I am now Suellyn Rudman. I am married to a wonderful man named Richard. He is a broadcast engineer. He is the chief engineer for two broadcast stations here in Los Angeles. Our marriage has been like a dream come true and I am very, very happy.” Haunting, for the way in which Rudman’s narrative echoes that of Lolita. When Lolita eventually escapes Humbert and Quincy, when she escapes from the promise of money, urbanity and fame her two abusers offer in exchange for her body, she settles down to a modest life as a housewife – with a man named Dick.