-detail.jpg)

Thornton Dial, Stars of Everything, 2004 (detail). Mixed media, 248.9 x 257.8 x 52.1 cm. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, Atlanta. © 2022 Estate of Thornton Dial / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London 2022. Photo: Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio.

Royal Academy of Arts, London

17 March – 18 June 2023

by DAVID TRIGG

An animal skull at the centre of a dilapidated record player warns potential listeners to keep their distance in Lonnie Holley’s Keeping a Record of It (Harmful Music) (1986). Referencing the racist assumption in 1950s America that music created by black people was “dangerous” to sensitive white ears, the sculptural collage is a highlight of Souls Grown Deep Like the Rivers: Black Artists from the American South at London’s Royal Academy, which showcases work by 34 artists born between 1887 and 1965 who for decades worked almost entirely without recognition from the established art world.

Lonnie Holley, Keeping a Record of It (Harmful Music), 1986. Salvaged phonograph top, phonograph record, animal skull, 34.9 x 40 cm. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, Atlanta. © 2023 Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London. Photo: Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio.

While millions of black people moved from the rural south to cities in the north during the Great Migration of 1910-70, these artists stayed behind, making works rich in personal, social and political symbolism that responded powerfully to the injustice, discrimination and economic hardships their communities endured. None received formal artistic training, learning their skills instead from friends, family and the physically demanding jobs they took in construction and welding. Inspiration was found in everyday life, historical events, religious faith, music and African traditions.

.jpg)

Ralph Griffin, Eagle, 1988. Found wood, nails, paint, 88.9 x 110.5 x 55.9 cm. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, Atlanta. © ARS, NY and DACS, London 2022 Photo: Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio.

With conventional art materials in short supply, these artists worked with whatever came to hand and the Royal Academy’s Gabrielle Jungels-Winkler Galleries are crammed with objects made from scrap metal, old clothing, used paint tins, driftwood, furniture, animal bones and other objects collected from around rural Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. Artists such as Thornton Dial and Charlie Lucas used industrial castoffs to create their welded-metal sculptures, while others, including Ralph Griffin and Bessie Harvey, were drawn to the organic forms of tree branches, roots and other natural materials. Griffin’s majestic sculpture Eagle (1988), comprised from pieces of wood sourced from a creek in Burke County, Georgia, is typical of the talismanic sculptures that filled his yard and home.

.jpg)

Thornton Dial, Stars of Everything, 2004. Mixed media, 248.9 x 257.8 x 52.1 cm. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, Atlanta. © 2022 Estate of Thornton Dial / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London 2022. Photo: Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio.

In Dial’s Stars of Everything (2004), a downtrodden American eagle dressed like a tramp protrudes from a colourful constellation of stars made from splayed paint cans; a self-portrait of sorts, it speaks to the artist’s enduring belief in art, despite being ignored by an indifferent art world. For Dial, birds denoted freedom and autonomy, yet such liberties are denied to the lifeless creatures in his collage Blue Skies: The Birds that Didn’t Learn How to Fly (2008), which depicts a row of dead blackbirds made from scraps of fabric hanging from a washing line. It is a haunting work, evoking the horrific lynchings and racial intimidation suffered by African Americans during the Jim Crow era. Though attesting to a specific moment in the troubled history of America, it speaks of a continuing struggle for justice that resonates beyond the deep south.

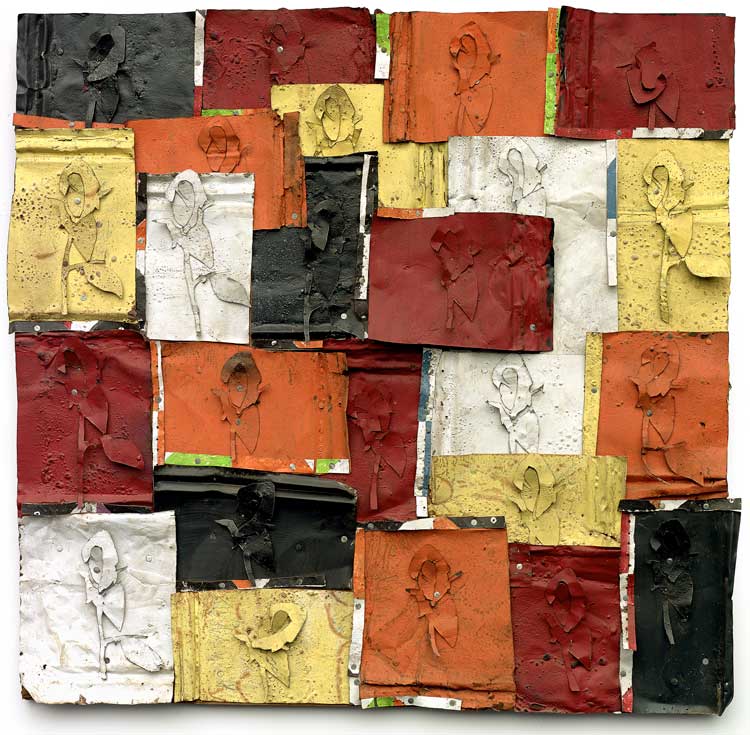

Ronald Lockett, Sarah Lockett's Roses, 1997. Tin, nails, and enamel on wood, 129.5 x 123.2 x 3.8 cm. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, Atlanta. © ARS, NY and DACS, London 2022. Photo: Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio

Dial’s influence hangs heavy over this show; he mentored several artists here, including his sons Thornton Jr and Richard, as well as his cousin Ronald Lockett. He also knew many of the quiltmakers living in Gee’s Bend in Alabama and there are formal similarities between his assemblages and some quilt designs displayed in the exhibition’s final room. Richard Dial’s extraordinary steel and wire sculpture Which Prayer Ended Slavery?(1988) shares his father’s sociopolitical concerns as much as it does his artistic inclinations. The highly stylised tableau depicts three black figures being subjected to degradation, torture and death at the hands of a white figure, while, above them, two more figures are engaged in prayer. It is a stark reminder of the evils of racism, while calling into question the role that religion played in the perpetuation of slavery as well as its abolition.

Martha Jane Pettway, "Housetop"— nine-block "Half- Log Cabin" variation, c1945. Corduroy, 182.9 x 182.9 cm. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, Atlanta. © Estate of Martha Jane Pettway / ARS, NY and DACS, London 2022. Photo: Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio.

Religious iconography appears elsewhere in the work of Mary T Smith, a former domestic servant who transformed her yard in Hazlehurst, Mississippi, into an outdoor gallery. Her minimalist assemblage, He (c1980), reconfigures an old tyre rim, a splintered piece of wood and a scrap of tin into a simple yet strangely moving image of Christ on the Cross. The crucifixion is also the subject of Joe Minter’s semi-abstract sculpture And He Hung His Head and Died (1999), which uses industrial brackets and pieces of scrap metal to reimagine the three crosses of Calvary. Reflecting Minter’s keen eye and deeply held faith, it is an understated yet potent piece of contemporary religious art.

Joe Minter, And He Hung His Head and Died, 1999. Welded found metal, 243.8 x 194.3 x 87.6 cm. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, Atlanta. © ARS, NY and DACS, London 2022. Photo: Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio.

Like Smith, many artists created large-scale, site-specific installations on their properties, which were known as yard shows. Several sculptures from these shows are included here, but seeing them transplanted from the deep south to the heart of Mayfair leaves you yearning to know more about the context in which they were made and displayed. An all-too short video presentation of Minter’s sprawling African Village in America gives us a taste of the remarkable yard show he has been creating in Birmingham, Alabama, since 1989 which, through countless works made from thousands of found objects, references 400 years of African American history.

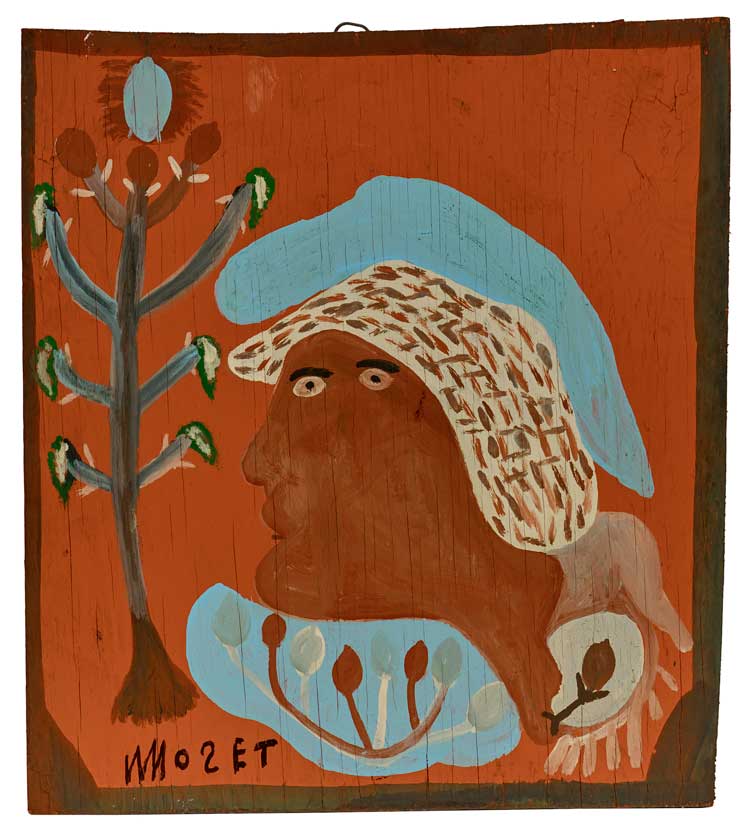

Mose Tolliver, Mary, 1986. Housepaint on wood, 50.8 x 45.7 cm. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, Atlanta. © Estate of Mose Tolliver / DACS 2022. Photo: Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio.

There is no doubt that these artists’ works are of historical importance, but how many aspired to enter the established art world that had shut them out? We learn from the catalogue that when Lockett expressed his ambition to go to art school, Dial discouraged him: “He told me I had the best school of all just making artwork,” Lockett recalled. “He helped me to find out that you could take tin or barbed wire or different small little metals and make things out of them.” His words almost suggest a preference for working outside the system, which begs the question of where, really, do these artists belong? In the grand surroundings of the Royal Academy, their works seem sanitised; divorced from the context of their production, they are robbed of their lifeblood.

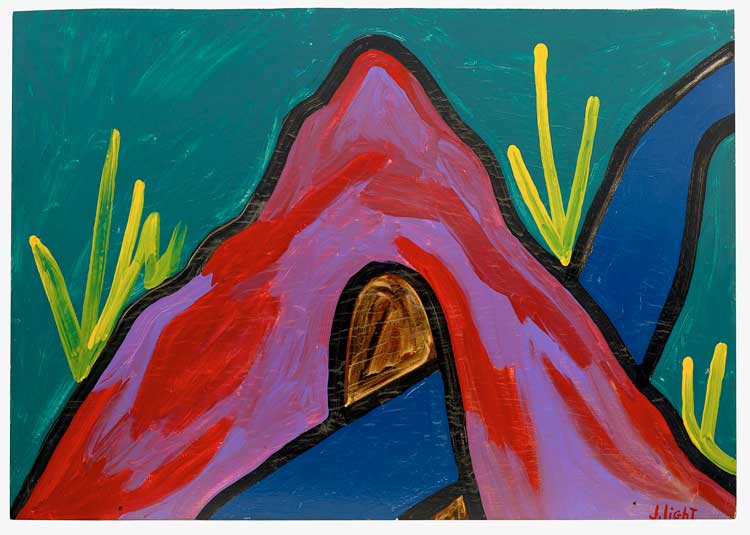

Joe Light, Blue River Mountain, 1988. Enamel on wood, 81.3 x 121.9 cm. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, Atlanta. © ARS, NY and DACS, London 2022. Photo: Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio

The exhibition takes its name from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, established in 2010 by the late Georgia-based art collector William Arnett to preserve and place into museum collections the works he acquired by black, southern US artists. Arnett was adamant that these artists are no less worthy than Robert Rauschenberg or Jasper Johns and, indeed, it is hard not to think of Rauschenberg’s Combines when confronted with works such as Dial’s bed-like collage Mrs Bendolph (2002). Rauschenberg never hid the fact that he was inspired by his visits to yard shows but, unlike the objects he saw there, which were informed by a specific set of social conditions, his art was made with an awareness of the twists and turns of art history. How, then, do museums best accommodate practices that developed beyond the confines of the established art world, without formal education or instruction in the visual arts?

Marlene Bennett Jones, Triangles, 2021. Denim, corduroy, and cotton, 205.7 x 157.5 cm. Souls Grown Deep Foundation, Atlanta. © 2023 Marlene Bennett Jones / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London. Photo: Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio.

The artists included in Souls Grown Deep Like the Rivers are often referred to as “self-taught”, “outsider” or “visionary” – epithets that, according to Arnett’s foundation “emanate from a market-driven bias against artists of colour”. What this show demonstrates is that art history remains a work in progress. In providing a welcome introduction to the works of these extraordinary artists, it reveals there is still more work to be done if they are to truly find their home in the canon of American art history.