Sol Calero: ‘They insisted on covering the fissures, but the walls still perspired’

Zora Mann: Waganga

Shailesh BR: The Last Brahmin

Villa Arson, Nice, France

14 February – 3 May 2020

(Please note that due to the nationwide lockdown imposed by the French government because of the Coronavirus, these exhibitions are temporarily closed.)

by HARRIET THORPE

At the Villa Arson, an art centre, art school, library and artists’ residence in Nice, a new season of three exhibitions has opened. The solo exhibitions draw from the four-month artist residencies of Sol Calero, Zora Mann and Shailesh BR, each invited to the villa by the director, Éric Mangion, who has spotted the potential of many emerging contemporary artists moving into their mid-careers.

The art centre sits at the heart of the sprawling Villa Arson complex overlooking the city and the Bay of Angels, and each exhibit is located in a different space. From an 18th-century mansion grows an organic extension of terraced brutalist buildings and gardens, designed in the 1960s by the architect Michel Marot. The Bosco, a concrete maze of layered streets, plants and patios, is brought alive by the art students who can be found sketching in its hidden corners.

The architecture of Villa Arson finds its way into each exhibition. Central to the exhibition by Calero is the organic decay of the gallery walls where she worked. For Mann, previously an art student at the Villa Arson, the building was a familiar canvas from which to work. The concrete terraces of the complex feature in the first video work of Shailesh BR, who is filmed performing a ritual act on the site.

[image4]

Sol Calero: ‘They insisted on covering the fissures, but the walls still perspired’

The Berlin-based Venezuelan-born artist Sol Calero (b1982) started her residency at Villa Arson in Nice with the aim of slowing down after a busy few years of back-to-back shows. “It sounds like a cliche, but after months being here you can really understand why artists move here to paint,” she says of the city that so enchanted Henri Matisse and Marc Chagall.

Calero’s paintings, which depict fruits, plants, objects and sculptures, were already bright, but the two new paintings made during the residency take on a distinctly pinkish glow, just like the sunsets of Nice. These two works join the series Pasaje del Olvido, inspired by memories of summers with her grandmother in Venezuela. Gradually, Calero has seen her paintings becoming more gestural, reflecting the growing blurriness of her memories of her Venezuelan identity.

[image6]

Often creating interior scenes within her exhibitions, Calero looked to Villa Arson for inspiration when designing the show. “I fell in love with the architecture of the space,” she says of her exhibition rooms, where large windows, stepped transitions and high ceilings create a unique stage for art. Even when rainfall of tropical intensity hit last November and the building started leaking, with pools of water forming on the floors, it didn’t deter her. “Instead of fighting against the elements, I decided to include the problems of the architecture in the show. It was an exercise in trying to listen to what the building wanted to say – which is why the exhibition title translates roughly as: ‘We kept on covering the cracks, but the building was still sweating.’”

Calero worked directly on the exhibition space as if it were a canvas. She uncovered the cracks, removed mould, but preserved the destruction, intertwining her artwork into the fabric of the building. She built a bridge out of timber palettes for visitors to cross the space in case of flooding. She painted the walls to extend the architecture further – colour-matching the exterior red of the villa inside to create the impression of an interior patio and tracing the crisp patterns of light cast on to the walls in sky blue.

[image5]

Calero often hangs her paintings on coloured walls, and she has been increasingly using brown over the last few years. It is a reference to the landscapes of Latin America, historical ethnographic images and the indigenous paintings of the Cusco school of Peru, she explains. “Why do we always start with white?” she asks. For her, it is a political question, from which much of her research into ethnography, societal colour blindness and her own Venezuelan identity begins. “When I’m working with colour in art, I’m making a statement. Things can be different if colour is added.”

In the same way that the artists of the Cusco school added bright local colour to colonially influenced Catholic imagery, Calero brings books on South American art to Villa Arson, where none previously existed. Her reading room, which contains 30 books, features natural plants, a shelf-caddy on wheels and a daybed upholstered with Calero’s textile designs and decorated with ceramics made in the Villa Arson studios. After the show, the books will be donated to the library and the plants to the garden.

[image7]

For Mann, the residency at Villa Arson felt like a “time loop”. She first arrived there in 2009, as a student with an interest in figurative painting. When she left the school, she was working in monochrome, but now her work is full of colour, abstract symbols and charms composed with the softness of a dream. It feels apt that Mann has returned because her works reflect her personal journey – from childhood growing up in East Africa to her travels across the world.

The title of the exhibition, Waganga, refers to Kenyan healers who remove curses from the body, but it also explains Mann’s conceptual approach to the making of art. Growing up in East Africa, she once witnessed the ritual and saw a removed curse physically manifest as a stone, which she found “troubling” yet “fascinating”. She explains: “I titled the show Waganga because, in art, we manifest spiritual problems in a physical way. We find formal solutions to ideas, bringing out an energy and manifesting it in this realm.”

[image8]

Mann’s sculptural works form layers for the visitor to experience as physical manifestations of spiritual protection. A group of abstract wooden shields, or “boucliers”, as Mann refers to them, are intimately shaped to her own body. Some are dedicated to close family members, and one was made when she was studying at Villa Arson. A rippling curtain of tiny beads made of recycled flip-flops divides the space. The flip-flops are collected from the Kenyan shores by the charity Ocean Sole, where Mann previously volunteered. Beads, this time in ceramics, made in the studios at Villa Arson, are also splayed out on the wall in a new sculptural work that resembles a dreamcatcher.

[image9]

This exhibition is the first time that Mann has shown her watercolours, which she has been working on for the last two years. Watercolours are light relief for Mann, who likes the immediacy, changing colour easily, and the fact that she can make them while travelling. Although two-dimensional, the works have the same interest in layers and depth as the sculptures. Mann describes the content of one watercolour, which was made on the terrace of a cabin in Sweden: “This was a flower I saw in Santa Fe, here is the cabin with its big windows, there is the sea. It is a mix of exterior and interior spaces, and internal things as well.”

[image2]

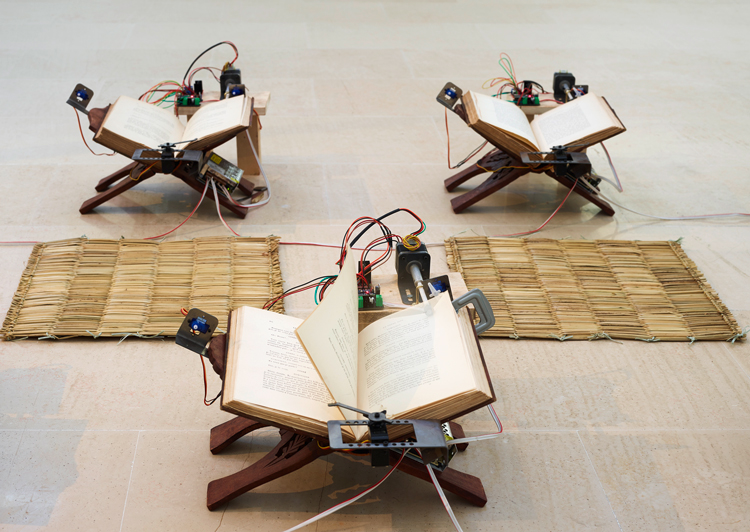

Shailesh BR, an Indian artist and Brahmin, and the show’s curator, Vitarka Samuh, follow the ritualistic life of a Hindu Brahmin in India through an exhibition conceptualised as a Brahmin’s house, a place traditionally seen only by the Brahmin himself. Installations of drawings, collages and automated machines form chapters that represent events from life to death, and the demanded repetitive rituals that surround them. As each machine repeats its motions, Shailesh BR questions the beliefs behind the historic role of the Brahmin, from the hereditary selection, to the monotony of the tasks necessary to the achievement of Nirvana.

While the caste system was outlawed in India in 1950, Brahmins are still at the core of the country’s local politics. The responsibility, as a bridge between Hindus and the gods, is held sacred, and questioning the Brahmin’s role is controversial. The exhibition in Nice was an opportunity for Shailesh BR to speak freely, and his very presence abroad is a statement in itself, as Brahmins are not permitted to leave the holy land.

The first work of the exhibition is an image of two Muslim men that Shailesh BR knew when the three of them were children, but with whom he could not be friends because he was a Hindu Brahmin. Samuh is from a Muslim family and the pair became friends after Samuh invited the artist to a residency he was hosting in India. The opening statement of the exhibition shows their joint interest in breaking down the borders of society and religion in India through art.

[image3]

The monotony of the Brahmin’s rituals is reflected in the clinking sounds of the machines and the repetitive nature of images, offerings or actions. A 2020 video work (Tail of a Dog (Shwapuchchha), developed over the course of the exhibition, documents the repetitive ritual of wearing the sacred thread that the Brahmin undertakes each day – 90 videos will be made over 90 days. A series of automated machines feature a page-turning device for learning the ancient Sanskrit knowledge, and a complex Puja [prayer] machine that replicates each stage of the ritual prayer process.

The Puja machine rings a bell to wake up the gods, offers fire, milk and flowers, and delivers a puff of spices into a growing pile of colourful dust. Samuh says Shailesh BR has “taken all the aspects of the worship and assigned it to a machine. So, the question is, if the machine can do the monotonous rituals of performing the Puja, then does the machine also become enlightened?”

Inspired by the layered collages of Anselm Kiefer and the quirky kinetic sculptures of Jean Tinguely, Shailesh BR uses art to lighten the load of these heavy philosophic questions central to his own life as a Brahmin. “My work is humorous, but it is not simple humour, it is black humour that reflects the current political scenario,” he says.