Timothy Taylor, London

16 September – 22 October 2016

by ANNA McNAY

Have you ever wanted to put your head inside a yeti’s skull, to converse with the ghosts of Himalayan explorers, or to jump off a parapet and into a snowy void? Well, now’s your chance. For his first exhibition with Timothy Taylor, Shezad Dawood (b1974) has transformed the Mayfair gallery into a disorienting space, with tantric wallpaper and a bright neon of Himalayan temples, that burns an imprint on to your retinas as you enter his unfamiliar world. Alongside this are two glittering white sculptures and six paintings-cum-screenprints-cum-collages. However, the pièce de résistance is a virtual reality work, inviting visitors to travel through time and space, secret passages and Himalayan foothills, in a simultaneously fantastic and nauseating (I never was good with motion sickness) experience, bookable ahead of time, and lasting up to 15 minutes, depending on the route you – and your guide – take.

The exhibition is set in Kalimpong, a real town in the Indian Himalayas, and one with a rich history at that. Once the gateway to Tibet, the town has seen many happenings. “Kalimpong is just quite wonderful,” says Dawood. “It’s hard to know where to begin. Everywhere, if you scratch beneath the surface, is a Pandora’s box of references. There are so many sedimentary layers of narrative.”

Home to the Himalayan hotel, which exists to this day, the town has seen a fascinating range of stories and characters pass through it, including Alexandra David-Néel, an early 20th-century Franco-Belgian explorer. The first foreign woman to enter Tibet in 200 years, she did so disguised as a beggar. The Russian theosophist and painter Nicholas Roerich, founder of the Roerich Pact for safeguarding antiquities and monuments, also ended up in Kalimpong. It was also the start point for many of the Texan billionaire Tom Slick’s yeti expeditions.

Nehru denounced Kalimpong as “a nest of spies” because it provided a Casablanca-like backdrop to various geopolitical shenanigans after the Sino-Soviet split, before the Sino-Indian war. Having spent an afternoon with Dawood, being thrilled by tales of espionage and Hollywood-style adventure stories (one even involving Jimmy Stewart’s wife’s lingerie case), I could go on regaling the joys of Kalimpong myself now, but that would be to overlook the artistic response to the exhibition – and it would also take away from the fabulous book, co-published by Timothy Taylor and Sternberg Press to accompany the show, which is full of thoroughly researched, yet creatively licenced texts on the theme, proving, if anything, that reality certainly can be stranger than fiction. “If I made it as a film,” Dawood laughs, “nobody would believe it – there are too many strands.”

The two sculptures on display are busts of the aforementioned David-Néel and Ekai Kawaguchi, a Japanese monk who felt the Japanese form of Buddhism was too tame and sneaked into Tibet to get what he felt was the real form. The pair became friends and Kawaguchi orchestrated David-Néel’s first meeting with the Dalai Lama in Kalimpong in 1912. The bronze sculptures are made from many different photographs, taken of each of them at different ages and different angles, thus becoming “quantum busts”, which are displayed as if in conversation. The bronze has been painted white and treated to recreate the crystalline quality of condensed, deeply compacted snow. Even the plinths have been specially designed to appear mountainous and craggy with a seamless, yet visible, join.

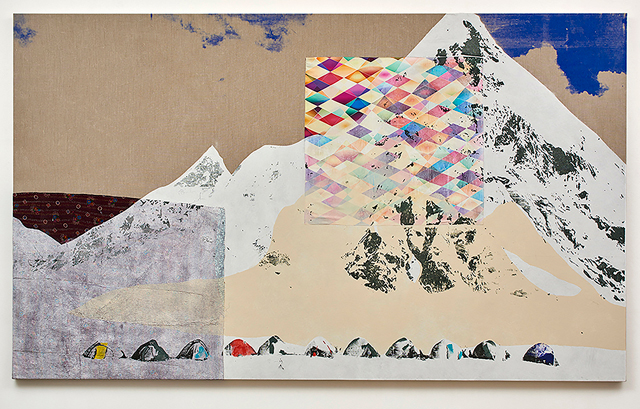

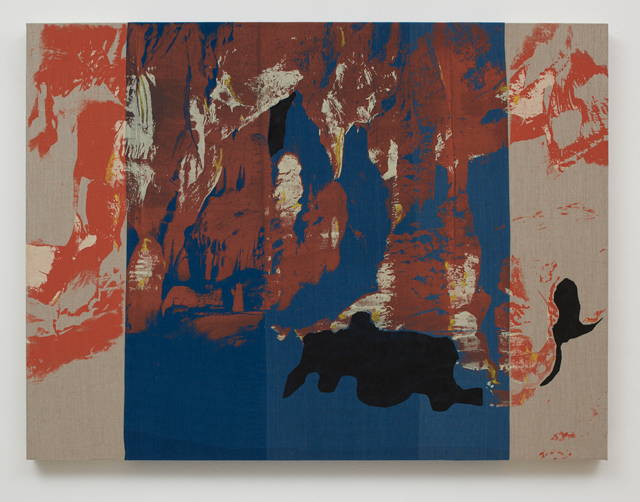

The canvas works expand on the lexicon of Dawood’s earlier cloth works, which regularly use Indian and Pakistani materials, by stitching in samples of Tibetan quilting and Indonesian batik, then painting over them in acrylic. The Cave Variations take cave interiors as their starting point and play with them to the point of abstraction. “The kind of painting I do comes after the forms of visual editing technologies,” explains Dawood. “I am interested in how these technologies feed back into the process of painting.”

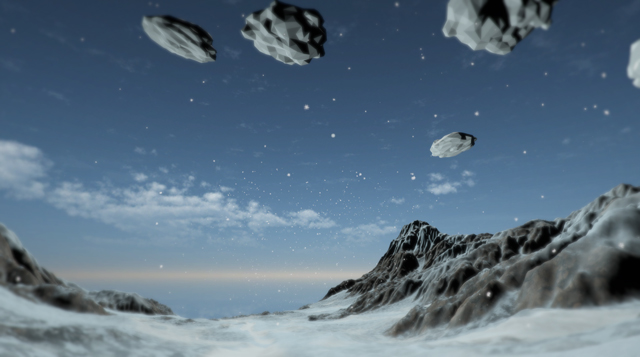

Cave Variation 1 (2016) looks like a wall with layers of paint peeling off, hinting at the stories hidden beneath. The dark black shapes recall the holes between universes in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy, drawing you in and pulling you through. In House 1 (2016), the white potato-print shapes in the blue sky could be either clouds or mountain peaks, an ambiguity that recurs in the deliberate crudeness of parts of the VR work, where Dawood has chosen to leave the polygonal building blocks as such, unrefined into more believably accurate representations, raising the question of what actually constitutes the real: “I tend to be quite left field in believing that the world actually was flat until 51% of people started feeding into the collective unconscious that it was round,” Dawood smiles. “The real is a social convention and the whole idea of the virtual is encapsulated from the very beginning in Buddhism – it’s about everything we see being a whole. The idea of puncturing the real is also puncturing the ego. Esoteric Buddhism is basically techno-speak from a few hundred years ago.”

“Everyone’s so concerned with making the virtual appear real, but why have we gone through Brecht, to assert the reality of the fictional?” Dawood continues. Accordingly, he has deliberately included things in the VR that disrupt the virtual space. He has applied an RGB glitch to the snowflakes, thinking backwards to the shift between analogue film and new media in the 70s and the limitations of the medium, wanting to be aware of that history and how one might move forward into the space of VR without just embracing it uncritically. Instead, he seeks to destabilise perception, without being too didactic, allowing visitors to enjoy themselves at the same time. A lot is drawn from the culture of gaming, and references are made to Super Mario World, as well as to Minecraft, and visitors are able to move around both by physically walking within the gallery space or by using a hand control to teleport themselves over glaciers, up on to balconies, and through closed doors.

Dawood has seemingly left no stone unturned with his rigorous research and execution and the show is mindboggling and fun, with the VR work making me repeatedly gasp out loud, not least as the rug was quite literally pulled from under my feet, dissolving to leave me floating amid the stars in the Himalayan night sky. Don’t miss out on this adventure of a lifetime – it unites art, history, technology and adventure in a way that really can only truly be experienced in the first person.