The National Gallery, London

13 April – 11 August 2019

by BETH WILLIAMSON

Exhibitions of contemporary art at the National Gallery in London are becoming the norm. These are especially interesting when, as is often the case, a contemporary artist is invited to respond to the National Gallery’s collection. Three years ago, Sean Scully (b1945, Dublin) was invited to do just that. Scully chose to take Joseph Mallord William Turner’s painting The Evening Star (c1830) as his point of departure.

[image9]

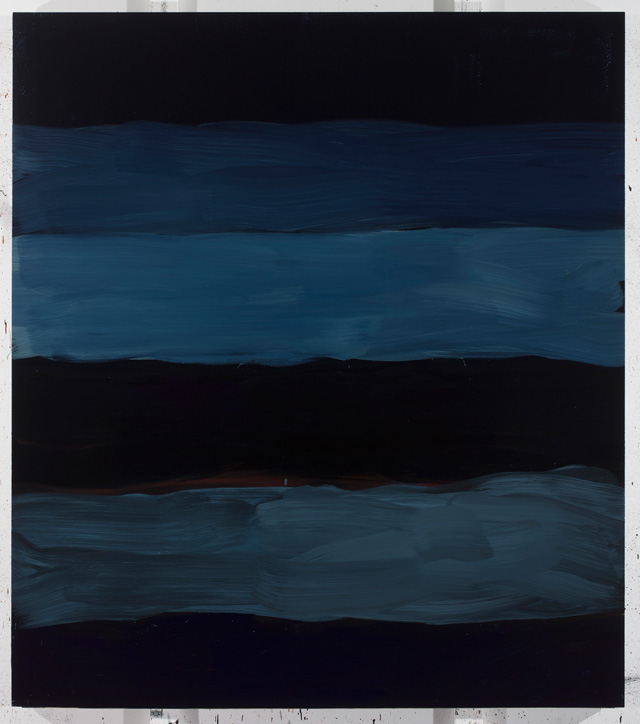

Set out in three linked gallery spaces on the ground floor of the National Gallery, Scully’s works are fresh and vibrant. The prevailing motif is one that he is well known for and his stripes and blocks of colour hover somewhere between European painting and its rich histories, and the unique nature of American abstraction. These are confident works and, like Scully himself, are undaunted by the venue or the presence of Turner’s The Evening Star. Scully likes to joke that he chose a work by Turner because Turner’s father was a barber like his own, but more important is their shared fondness for the Kent coast in the south of England. Turner attended school in the Kent town of Margate and visited throughout his life. Scully recalls a rare walk with his father in nearby Sheerness when he was about eight years old. His memories are acutely sensory – the slap of feet on wet sand, the rolling of the waves, the humidity of the air and the yellow-grey light at the end of the day. These sensations are what he recognises in Turner’s painting and what he explores in his own work shown here, especially in his Landline paintings.

[image7]

The Evening Star hangs in the centre of the first gallery space. It portrays a transitional moment in nature as the evening star first appears in daylight before giving way to the light of the moon. In the foreground of the shoreline, a small dog accompanies a boy with a shrimping net. Scully calls it an in between painting – between day and night, between land and sea. The Landline works in this room immediately demonstrate Scully’s interest in the horizontal nature of Turner’s The Evening Star. Meanwhile, Scully’s triptych Arles Abend Vincent (2013) is a response to Vincent van Gogh’s Chair (1888), the painting that Scully says “made it possible for me to enter the world of art and to think that I could actually make paintings”. There are other references to Van Gogh in the exhibition in the Arles Abend Deep (2017) triptych.

[image4]

If we walk into the second gallery space and look back, we can see Turner’s The Evening Star through the doorway, cleverly flanked by Scully’s Landline Star (2017) and Landline Pool (2018). While it is an obvious curatorial strategy to set the corresponding works in dialogue, it is an effective one. The neat twist here is that the relevant works are hung in different spaces – The Evening Star in the first gallery and the two Landline paintings in this one – which makes for more interesting possibilities. This spatial shift introduces a distancing, which perhaps allows more room for visitors to think about the temporal shift from the 1800s to now and to draw their own conclusions about how the works might be connected.

[image5]

The exhibition’s curator, Colin Wiggins, claims that this is a two-way dialogue, so, while Scully takes inspiration from Turner, Scully’s works enable us to appreciate elements of abstraction in the work of Turner. I am unconvinced by this last claim, although I do find myself sympathising with Wiggins’s belief that there is no such thing as abstract painting, in Scully’s case at least. Everything Scully paints is undoubtedly about experience, about somehow conveying that experience through a visual equivalence.

Other works in this space include Scully’s Human 3 (2018) series. While the images are constructed from his trademark stripes, squares and blocks of colour, the windows and doors they suggest invoke the human figure that might look through the window or walk through the door. This resonates with an idea that Scully is fond of, that his paintings hover between abstraction and representation. This makes more sense when he talks about different experiences that have influenced him, such as the acute poverty of his childhood and the death of his son, or the enduring impact of music, summers spent in Bavaria and visits to Morocco.

[image3]

Strands of influence are seldom singular and this is certainly the case for the works exhibited in the third and final gallery space. Let us consider, for instance, the student trip that Scully made to Morocco in 1969, and which has had a lasting effect on him. He has vivid recollections still: “After visiting Morocco, I became fascinated by cloth, by pattern and the pattern moved as it was carried around by the people.” In works such as Robe Blue Blue Durrow (2018) and Robe Magdalena (2017), there are clear references in the titles to cloth, but this is not straightforward as the titles include other references, too. Robe Magdalena references Mary Magdalene, the penitent prostitute of the New Testament, while Robe Blue Blue Durrow contains a reference to the seventh-century Irish manuscript The Book of Durrow, which Scully admires.

The largest painting in this room, and in the exhibition, is Landline China 8 (2018), painted by Scully precisely for the space in which it hangs. At three metres high and almost two metres wide, it is significantly bigger than any other work shown and it dominates the space. It references China’s ancient cultural history; the lucky number eight and a specific colour symbolism, such as red for good fortune. I do not doubt Scully’s interest in Chinese cultural history, but perhaps the painting is also self-referential. Scully has had five large exhibitions in China since 2014 and, given his artistic confidence, Landline Chine 8 conceivably celebrates that success.

[image2]

There are so many influences rippling through this exhibition that it is difficult to anchor everything to a single painting from the National Gallery’s collection. Turner’s The Evening Star was chosen by Scully and is posited as a central, but by no means sole, point of reference, so it seems curious to me that Van Gogh’s Chair, critical to Scully’s development as an artist, isn’t here, too. Still, this exhibition is encouraging in its ambition to bring contemporary art into dialogue with such an important historic collection and presumably it hopes to appeal to new audiences. Perhaps those who visit will be emboldened to wander through the main collection and seek out Van Gogh’s Chair.