MK Gallery, Milton Keynes

17 February – 2 June 2024

by VERONICA SIMPSON

The opening shot chosen for this first major UK show of US photographer Saul Leiter (1923-2013) is a telling one: a modest black-and-white photo sits between two introductory slabs of wall text, showing the back of a young woman’s head. The focus is on a pale twist of ribbon, which becomes the visual heart of the picture. Its dynamic zigzag shape somehow triggers awareness of all the movement around it: first the soft waves of her mid-brown hair, gathered towards this point, but also her movement through the city – there is no question, from the blurred greys around her that we are on the hoof and the context is urban. Other elements, such as the satin quality of her sun-kissed shoulders echoing the paler satin of the ribbon, register more slowly. It is a wonderful photo, in that it makes so much of so very little. And that is all down to the artistry, the eye, of Leiter.

[image6]

The young Leiter was set to be a rabbi, following his father into the Jewish ministry. But in 1946, he abandoned this course and headed to New York, causing an enduring rift with his family. New York was the epicentre of a new contemporary art scene centred around abstract expressionism, and Leiter wanted to be part of this. He aspired to be a painter, but it was photography that proved his calling, enabling him to make a living through fashion shoots for Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue and Elle, among others. It was not until 1980 that he gave up his professional studio to focus on his personal, artistic practice as a painter and photographer – and it was 2006 before he gained real recognition for the latter, thanks to the publication of Saul Leiter: Early Color.

[image8]

Now, he is viewed as one of the most important postwar photographers, feted for his street scenes of New York of the 1950s and 60s, and his pioneering use of colour.

There are 171 photos here, revealing Leiter’s talent for finding the sublime in the everyday. It is how he frames his subjects, the ordinary people, ordinary scenes, that reveals his artistry, as well as his influences. He was aware of the work of Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, and apparently friends with Franz Kline, Diane Arbus, John Cage, Robert Frank, Willem de Kooning, Andy Warhol and Robert Weaver. But his inspirations extended further afield: he loved Japanese woodblock ukiyo-e prints and sumi-e ink prints as well as French post impressionists, Édouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard. And all of that is visible on these walls.

[image11]

There is a photograph from 1957, Through Boards, that has Rothko embedded in its compositional DNA: a sliver of an urban street scene is horizontally sandwiched between dominant slabs of dark red and black, reminiscent of Rothko’s colour field paintings.

His impressionist or post-impressionist leanings encouraged experiments with images in which light and colour are fractured through moisture, from mist to rain, such as Lanesville (1958), a print of rain-soaked countryside viewed through a window.

[image16]

He comes across as a man in love with his times – the optimism and vigour of New York in the middle of the 20th century – and this vibrant city. Infrastructure, urban or domestic, plays a key part in almost every shot. In the first, largely black-and-white, gallery, there is a particular trio of photographs with domestic infrastructure to the fore: either curtains or clothes loom largest in the composition, playing with perspective, with perception; through its inert bulk, it emphasises the constant movement and multitude of people in the street, whether seen beyond a ragged curtain, or viewed through a heavily swagged window frame.

[image12]

Cars, buses, trains, the buzz and thrum of motor and pedestrian traffic is almost audible. There is another shot that has an Edward Hopper-esque quality: Bus (c1954) gives us the flat silhouette of a hatted man’s head, framed within the window of a bus, surrounded by fragments of red, pink and black, a collage of wheel arch, windows, street sign. As the curator, Anne Morin, says in the wall text: “He photographed that which obstructs, hides and encloses, thus revealing hidden depths.”

[image17]

Even in the black-and-white nudes that appear further on in the show, there is always a room, a bed, a sense of everydayness that enhances the intimacy, the humanity. Another print also (and confusingly) called Lanesville (1958) has just a section of a woman’s face captured in a mirror; her head and arm lie in much softer focus, along the base of the shot. It conceals so much more than it reveals, so that the image becomes more haunting, more poetic. Is it the ubiquity of crystal-sharp images taken by our smartphones and the relentless, grabby quality of such photographs, when harnessed to the relentless machinery of social media self-promotion that makes these soft, supremely personal photographs seem so quietly compelling?

One of my favourite images in the show is so abstract that it is hard to know what exactly is being photographed: soft pulses of light appear in constellations across a warmly coloured scene. Leiter called it Music (1954). Another is the Japanese-esque Footprints (c1950): a bright-red umbrella animates an otherwise monochrome scene of footprints in snow on a New York pavement. It has all the elegance and economy of a haiku.

[image15]

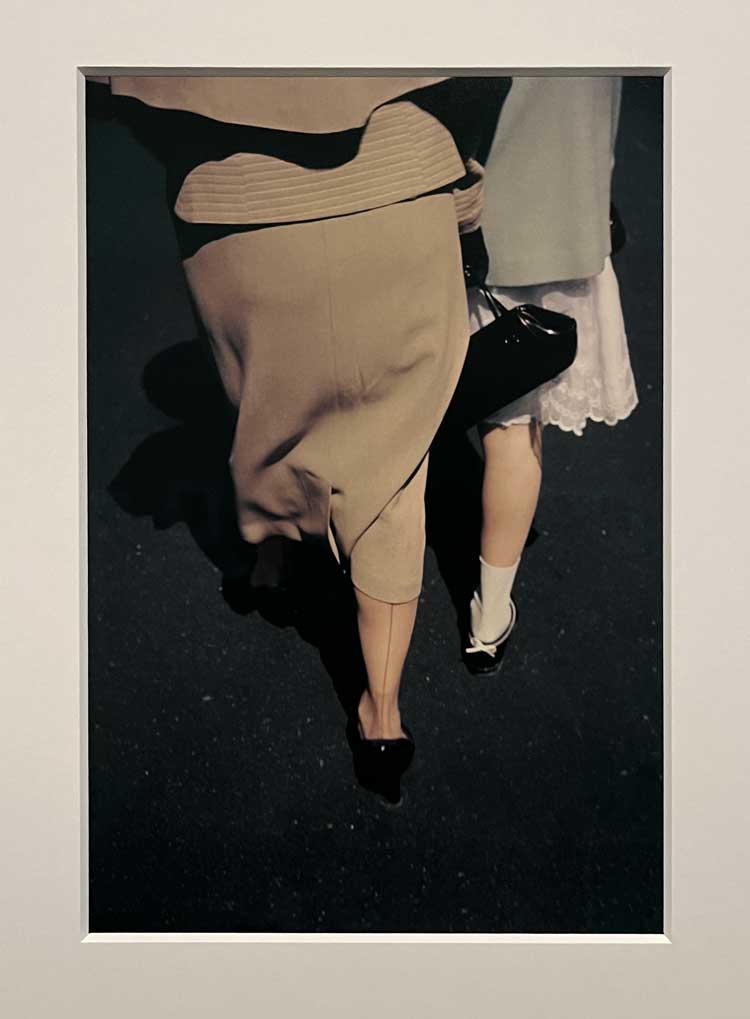

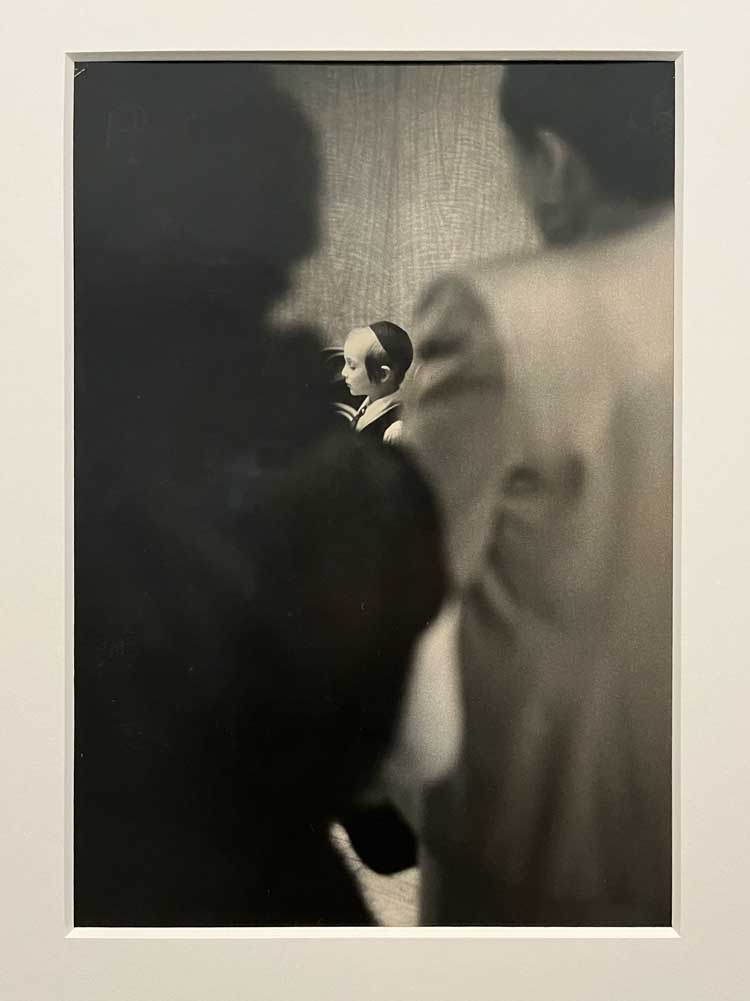

Doing more with less could have been his motto. A trio I particularly like further into the show gives us Party (c1953), in which we notice the proprietorial expression on the face of a dark and swarthy man, beside a slender woman whose polka-dot dress balloons around her; and in Wedding (1948), there is the small, clear image of the head of a boy in a skullcap sandwiched between two bulky, blurred shoulders of foreground figures. But I particularly love the pin-sharp observation and simplicity of Barbara and J, undated, in which Leiter photographs a woman and child from behind, striding forward, but zooming down on the firm backs of their legs, the one in white ankle socks, the other bearing the seam of a stocking. Every bit as intimate, amusing, observant as a facial portrait.

[image14]

Leiter is not interested in representational accuracy, but atmosphere. When he does pull focus, though, he makes sure it packs a punch, as with the crisply rendered elderly woman (Untitled, 1950s), every wrinkle in her downturned face captured, the texture of her coat, scarf, the gleam of her glasses, vividly rendered, against a blurred backdrop of ordinary, urban Manhattan greyness.

[image13]

His use of colour is all subtlety and softness, as in one scene of a green car’s red brake light reflected on a rainy Manhattan street. He rarely goes for boldness or intensity – except in that aforementioned red umbrella. These days when photographic imagery is omnipresent, utterly unreliable and often unsubtle, you can see the appeal of this reappraisal of Leiter’s unique gifts.

As well as the photographers, there are about 40 of his paintings here, ranging from small, charming sketches of people to modest, impressionist/expressionistic abstracts in which his feeling for colour is more exuberant. Not quite masterpieces, but a joyous, uninhibited counterpart to the captured intensity of his photography. The whole show feels like a love song to a vanished, analogue world and a different way of looking.

[image5]

-Saul-Leiter-Foundation.jpg)

-13.jpg)

-25.jpg)

-47.jpg)

-63.jpg)

-65.jpg)

-Saul-Leiter-Foundation.jpg)

-Saul-Leiter-Foundation.jpg)

-Saul-Leiter-Foundation_Courtesy-Florence-and-Damien-Bachelot-Collection.jpg)

-Saul-Leiter-Foundation-(1).jpg)

-Saul-Leiter-Foundation.jpg)