Chapel, Yorkshire Sculpture Park

4 January – 15 March 2020

by VERONICA SIMPSON

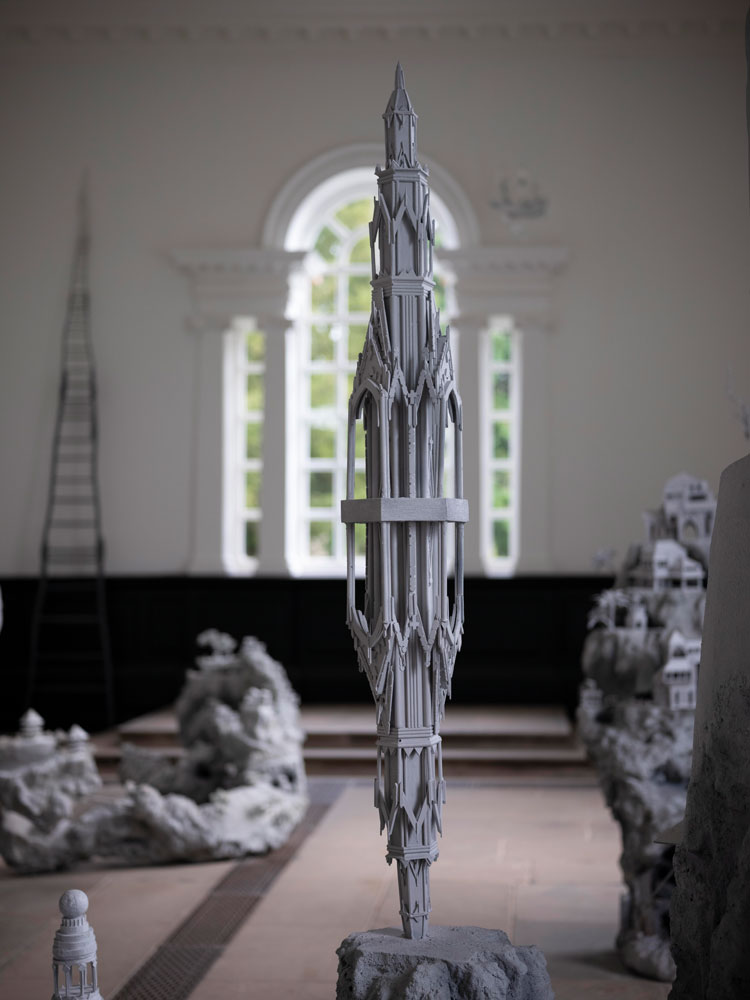

It would be hard to imagine a better setting for the latest work by British artist Saad Qureshi (b1986, Bradford). With Something About Paradise, Qureshi translates a crowd-sourced multitude of ideas about paradise into a singular interpretation of this mythical realm and its architectural and geographical features, represented by three pale-grey, sculpted islands emerging from the flagstones of the numinous space that is Yorkshire Sculpture Park’s 18th-century chapel.

Qureshi likes to delve into the collective folk consciousness in preparation for his works. This exhibition is the culmination of months of travelling around the UK, speaking to communities of all kinds and all faiths or none. He says: “I was born into a religious household, where the Qur’anic allegories of the seven heavens formed part of the backdrop to family life.” He was surprised, as his social circle expanded, to realise that not only were there other versions of paradise, but that the idea had traction even with those of no religion or faith. Speaking to Studio International before the opening of this show, he says: “This fascination was in my head for a long time before it started to take shape as an art project.”

[image8]

The urge to stage this art project, specifically on this site, took form in 2017, when Qureshi was commissioned by YSP curator Sarah Coulson to create a new work for Tread Softly, a group exhibition curated from the Arts Council collection. With Coulson’s encouragement, his Paradise proposal won funding from the Arts Council England and his gallery, Gazelli Art House, London. Thus, his journey into the contemporary British imaginings of paradise began. With each group he spoke to, he says he asked two key questions: “What does paradise look like to you? And what informs that understanding? I got such a vast variety of answers: from very pure, untouched natural landscapes to religious buildings, from very modernist architecture to cottages, or even tree houses. Some people had really basic expectations – a little cottage somewhere; something very manageable and doable. Other people had really massive expectations: palaces and Romanesque towers. This was rich material to translate into a body of work. Then once I had conducted all my research I sat down in my studio.”

[image10]

The resulting variety and also delicacy and detail of the structures that festoon his three “islands” and the other works that accompany them is breathtaking. He describes his process as a form of play, allowing the ideas to emerge through making. The three islands are built out of steelwork and Celotex – the expandable insulation foam so beloved of builders wanting a quick-fix. Qureshi says: “I can’t think of another material that would allow me to do this kind of carving process, with such immediacy. We sprayed it and then clad it, because you can buy sheets of it as well. Then I carved it away. There’s a lot of carving in my process. I really treat every material like clay: taking things out, adding things on, cutting it apart. Even though we were working with steel, we were cutting things off, welding them back on again. We were standing back and thinking: what do we have going on here?” Describing himself as a “control freak”, Qureshi works with only one assistant, who helps, he says with the structural process, but then Qureshi does all the modelling. He adds: “More than the issue of control, being an artist is about recognising a moment when something happens. When you say: ‘That’s it. The work has now come alive. Now it’s like a breathing thing.’”

[image11]

Qureshi knew from the outset that the work should all be one colour – this pale grey, a kind of non-colour - with a shared materiality. “I wanted to give it all one uniform treatment. Colour, for me, brings reality; it grounds something in the here and now. If you remove the colour it can push slightly away into distant reality. Then you look at the shape and form, and those things ping out more. Colour can be a bit of a distraction.”

Having enough detail to convincingly transport the viewer into the landscape is important, but so are the elements that suddenly remind you that, as Qureshi says: “It’s not quite what you think it is. It’s really dipping in and out of this fantasy, this dream world.” A lack of consistency in scale reinforces an otherworldly quality; Alice in Wonderland-style juxtapositions abound, as do abrupt shifts in orientation, with dwellings placed sideways on to these rugged structures, or even upside down. Disorientation is augmented with ladders that dangle from doorsteps, into thin air. Qureshi’s technique of slicing into these islands to reveal the metal and Celotex infrastructure also reminds us, abruptly, that this is all an illusion.

[image14]

This delightful chapel, with its multiple arches, alcoves and apertures, also resonates with the theme of thresholds – something integral to any version of paradise, as a destination between worlds, which one somehow has to access. Gates came up early in his brainstorming, but Qureshi initially resisted. “Pretty much everybody talked about them. I wanted to ignore them for as long as I could. And I did. It’s such a cliche – the ‘gates of paradise, blah blah’. And I thought I need something more, something meatier. But then I thought, I can’t carry on not looking at these.” So he immersed himself in the wrought-iron gallery of the Victoria & Albert Museum in London and came up with seven grey gates that are a composite of many different gates, from the religious and ceremonial to the secular. Only five of them appear in the gallery, however.

[image4]

He says: “I wanted to work with the number seven. It is hugely significant across religions and cultures. I decided that, if I make seven gates that would be great. I made seven and then we could only show five. In my head, I’m still satisfied. There are five gates here and two elsewhere.”

[image7]

Three additional pieces complete the Paradise ensemble. One, which is probably my favourite, dangles in the right-hand alcove set below and within the chapel’s dark, wooden balcony structure: a pale, dusty moon, pockmarked and luminous, featuring its own lopsided palace.

[image2]

The second is a flying ship, equally ethereal, which hangs to the right of the far window. The third is a ladder that leans against the wall on the left of the same window. It recedes in scale from human-sized at its base to miniature and elf-scaled at its top, in an obvious play on perspective.

[image15]

Qureshi says: “I thought these satellite pieces were really important to put everything in context. I don’t want to talk about the individual references, but literally everything here comes from stories that I’ve heard and collected, and it’s really important that I don’t reveal their origins. I need to let the work stand on its own ground and tell its own story.”

I ask: “Is this ladder a stairway to heaven? At face value, it’s clearly a ladder that won’t take you anywhere.” Qureshi laughs, and says: “But in your head it will.”

.jpg)

-2.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)