Whitechapel Gallery, London

9 September 2011–26 February 2012

by REBECCA WRIGHT

This outlook is surprising, not because it is out of character on the artist’s part – Rothko had spoken of a connection between his art and British Romanticism, of being drawn to the work of JMW Turner – rather this phrase appears unexpected because of the ghettoisation of Abstract Expressionism as the first distinctly American art form.

True or untrue, myths surrounding the early funding of the movement by the CIA in order to affect a form of American cultural Imperialism stick to the group; as does the pivotal position it holds in the canon of art history, as the turning point when ‘art’ migrated from Europe to America following the Second World War. By using a past exhibition as a case study (Rothko’s first solo show held in 1961) Rothko in Britain manages to break down the “Americanness” of Abstract Expressionism, revealing to us a fascinating dialogue established between artists on either side of the Atlantic.

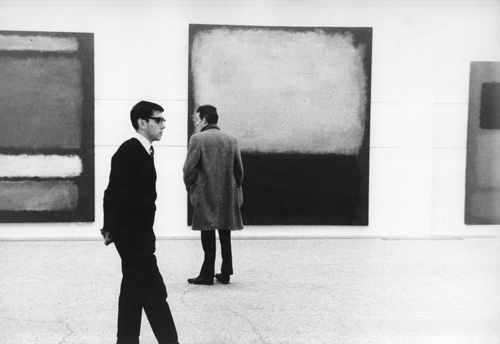

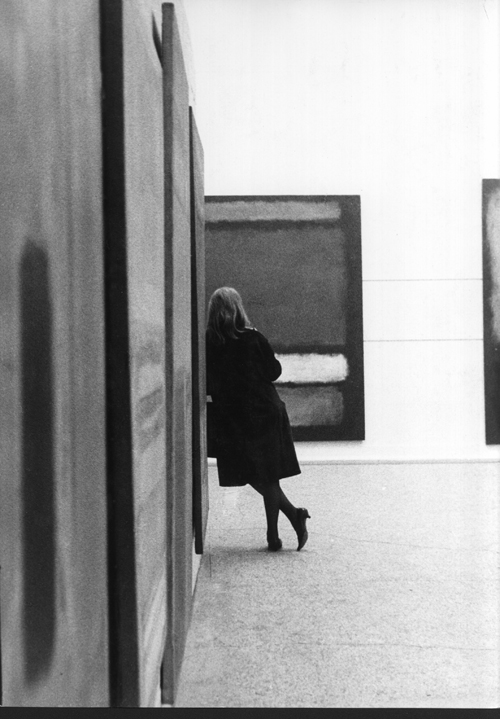

Bryan Robertson, curator of the Whitechapel Gallery from 1952 to 1968, was famous for his groundbreaking exhibitions that brought American artists such as Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell and Franz Kline to London. Rothko’s first solo show in London opened in 1961 and took London by surprise. In beautiful photographic records of the show taken by the young photographer Sandra Lousada we see a public agape, mesmerised by the paintings that were unlike anything they had seen before. In these pictures men and women of all ages are dwarfed by the large, geometric canvases. The atmosphere is solemn. What is captured is a poignant moment in history.

In a series of audio recordings we hear the recently deceased artist John Hoyland recounting the sensation of going to the exhibition. He remembers how, “we didn't understand it … how to analyse it". Art critic Tom Rosenthal also describes his experience, speaking of how the paintings confounded his hostile attitude to abstract art and abstract painting. With only one Rothko painting – Light Red Over Black (1957) – hanging majestically in the show, an archive of memory is established, shifting the artist from his position at the centre of the exhibition and chronicling instead a history of reception and impact through the recollections of others.

Rothko’s connection to Britain and British art is also explored through a trip he took to St Ives in the summer of 1959, where he stayed with the artist Peter Lanyon and his family. Included in the exhibition is correspondence about this trip and photographs showing large family meals with Rothko sitting by. This addition to the exhibition is fascinating for the way in which it disrupts the prevailing tendency to consider each movement within strictly national boundaries. In one sound recording, fellow St Ives’ artist and resident Paul Feiler describes St Ives as a hub which most American artists travelling to England would visit and as such it was not exceptional for Rothko to be making a trip to St Ives at that time. Although the St Ives School has, at times, been presented as derivative of Abstract Expressionism, by exploring how American artists made the pilgrimage to St Ives to make contact with British artists this exhibition confounds any accusation of imitation. Instead, it reveals a collaborative dialogue in which artists from either side of the Atlantic are growing and learning together. It somewhat levels the geographic playing field, no longer pitting Abstract Expressionism as the dominant player, but presenting both groups as preoccupied with a similar endeavour.

In this exhibition Rothko’s work is experienced counter-intuitively. The instructions Rothko gave to the gallery about how he wanted his paintings hung – their specific height and the correct lighting to be used – remind us that Rothko intended his work to be transcendental. It is this emotional, spiritual quality gleaned from Rothko’s canvases that has paired him and fellow Abstract Expressionists to the discourse surrounding the sublime. If Rothko’s content is the ungraspable, intangible and ethereal sublime, this exhibition offers in contrast the physical archive, something concrete to cling to when his work eludes us. If Abstract Expressionism and the contemplative work of Rothko encouraged the white cube display inherent to the reception of modernism, within this exhibition the white cube has been replaced by history and context. We witness the work in a very different way than we did in the Rothko exhibition held at Tate Modern in 2008–09, and also in the 1961 Whitechapel exhibition. We do not peer, or contemplate, as do the figures in Susan Lousada’s photographs; we respond to Rothko not through our senses, but through the built-up memories of others and through the archive. This is not a negative aspect, as through this historical approach to Rothko’s work we learn not only about the international nature of Abstract Expressionism, but also about that of the St Ives School. Whitechapel Gallery suddenly becomes a portal, an historically critical meeting point for different locales that upsets art history’s prevailing sentiment that with Abstract Expressionism, modernist art relocated from Europe to America.