Jupiter Woods, London

21 June – 28 July 2019

by TOM HASTINGS

Moira Stuart surveys the approach to Jupiter Woods, an art organisation based in south-east London. Known for her neutral expression, the broadcaster and newsreader here appears on a poster advertising Studies for Impartiality, a solo exhibition by artist Rosa Johan Uddoh that is devoted to Stuart’s image. She is an interesting choice of subject for Uddoh (b1993, Croydon), whose emerging practice makes space for radical self-love through an exploration of popular cultural forms from a black feminist perspective. In 1981, working for the BBC, Stuart became Britain’s first black female newsreader on national television. Her image was transmitted to Britain’s households throughout the 1980s, 90s and 00s, her voice framing events from the Gulf war to the Queen’s speech. Hers was, and is, a recognisable face in a sea of whiteness, providing a role model for young black and brown people under- and misrepresented by the media; yet, as officiator of the soft power of the BBC, it is one simultaneously constrained, for the account of events she relays is subject to state-sanctioned lines.

[image7]

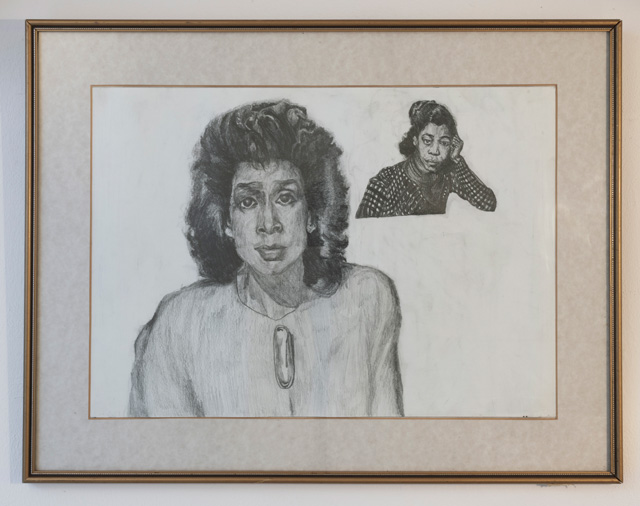

With Studies for Impartiality, Uddoh explores this tension by juxtaposing media, including screenprinting, performance and drawing, whose distinct qualities themselves dramatise the tension between a repressive apparatus and an affective imaginary. The power of this exhibition, in other words, lies in the way Uddoh mediates a politics of (dis)identification through forms determined by histories of cultural production, ranging from pop art and the Situationist International to the Black Arts Movement, that themselves engage or facilitate audiences in different ways. For example, lovingly rendered pencil drawings of Stuart, as if sent through the post by an adoring fan, are interspersed among photographic screenprints, in turn reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s series of superstars such as Marilyn Monroe and Muhammad Ali, that dominate the exhibition space.

[image10]

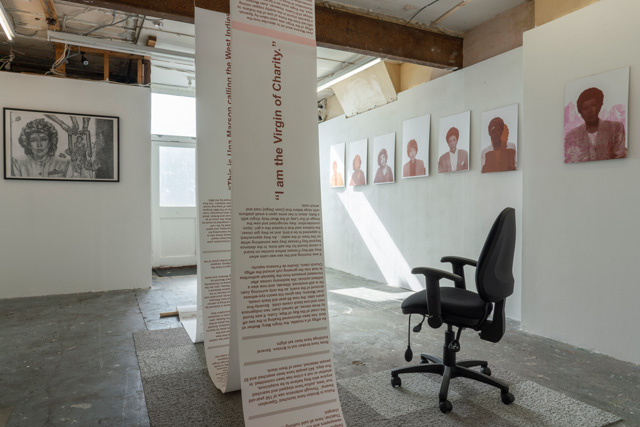

Passing the threshold, one is met by a series of Moira Stuarts in printed grades of brown, ochre and umber, each screenprint capturing her at a different phase of her career. These jump cuts are indicated by generational shifts in style, from shoulder-padded suits and cropped hair to ornate jewellery and a perm. For, bar these markers, Stuart appears ageless, her features rendered diaphanous in print. By repeatedly reproducing Stuart in this way, Uddoh severs her image from the fast-paced tempo of the newsroom: a trusted conveyer of information becomes the stilled object of our gaze. Separated from such televisual furniture, the many renditions of Stuart’s head and shoulders form a carousel that prompts the viewer to see her facial expression and bodily comportment as a conventionalised series.

[image11]

Her image is both imbued with meaning – each print comprises a unique arrangement of block colour and texture – and, because there is no obvious anchorage, emptied of significance. Uddoh deploys a silhouette to highlight or obscure Stuart’s face in various instances, manipulations that draw attention to her palette’s epidermal quality. In several prints grouped in a corner, Stuart is framed by a deserted mountainous terrain rendered in pink; this otherworldly landscape – which, as I later learn, depicts the Semien mountains in northern Ethiopia – introduces a sci-fi dimension that casts her anew as a holographic messenger whose missives reach us as a distant signal. By partially restoring her function through this locational cue, Uddoh suggests that we think about Stuart’s agency in an expanded sense: what might she, in her capacity as newsreader, convey besides an impartial account of the news, and to whom?

[image8]

This question is elicited again as I shift from one print to the next, for my passage clockwise around the gallery space is obstructed by Stuart’s characteristic lean to the right, as if she were motioning her audience to slow down and take stock. Her body arched to one side, Stuart silently and insistently occupies the space of Jupiter Woods, galvanising the viewer to reflect on the kinds of mediation in play. As Sara Ahmed has written: “Those who are not going the way things are flowing are experienced as obstructing the flow. We might need to be the cause of obstruction”.1

Uddoh, who recently graduated with an MA from the Slade in London, has examined the institution with a similar insistence. In October 2018, she co-organised an interdisciplinary conference titled Widening the Gaze, introducing its aims and objectives by singing Diana Ross’s 1970 hit Ain’t No Mountain High Enough. Arranged under the new title Why Are All My Tutors White, Baby?, her rendition of Ross’s song featured reworked lyrics that served to highlight the gap between the university’s diversity policy and the reality of the situation. In this and other works, Uddoh treats the fan’s over-attachment to a cultural icon as grounds for a performative act, inhabiting the icon – through what Elizabeth Freeman has termed “temporal drag” – in order to convey a history or message while raising the self-esteem of those involved through the familiar presence of a beloved person.2

[image5]

Stuart is a particularly effective subject in light of this strategy, for, unlike Motown singers such as Diana Ross, whose cultural production indexes their lived experience as black women, her image is constituted by a specific form, the BBC news broadcast, that is, in light of its blind spots and systematic racism, in some ways antithetical to such experience. As such, Studies for Impartiality performs a double action: first, Uddoh wrests Stuart from the broadcast, nurturing her image through the aforementioned prints and drawings; and second, she appropriates the news itself, producing subversive ends and effects. This she accomplishes through the exhibition’s opening performance, Auto Cutie, performed in collaboration with the diasporic dance troupe DIDD (Department for International Dance Development), of which she is a founding member.

[image3]

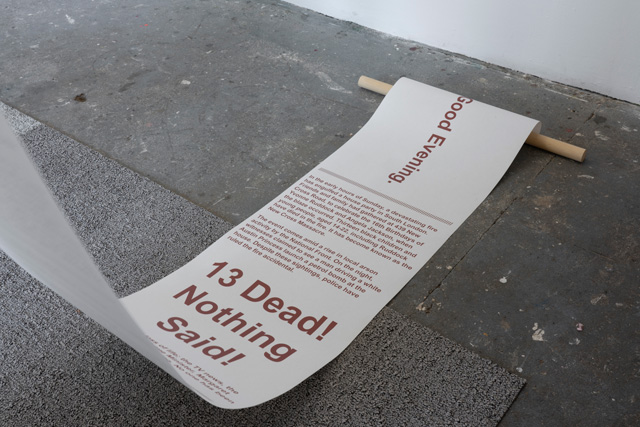

Dressed in a mint-green blouse, drab suit and wig, Uddoh commences the action by playing the flute from an office chair positioned on an ugly carpet sample in the centre of the crowded gallery room. In place of a teleprompter, two performers wearing maroon jumpsuits proceed to unravel a scroll that has been left lying on the floor, revealing passages of text printed in the same warm colours as the surrounding prints of Stuart. In a voice that contravenes the broadcaster’s standard RP accent, Uddoh reads aloud discontinuous episodes of text that cover topics ranging from incidents such as the New Cross Massacre in 1981, in which 13 young black people died at a house party in a fire that many believe was a racially motivated attack, to myths and stories from the European colonisation of the Americas.

[image4]

These passages are accompanied by commentary, such as: “Despite the huge loss of life, the TV news, the newspapers and the prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, have all said nothing. No one has been charged”, messages whose direct address is eerily contained by the impartiality of the news bulletin form. As the scroll is unfurled to a length of several metres, the audience is first penned in the gallery space, then marshalled on to the street, where the performance ends to rapturous applause.

[image2]

Auto Cutie is comparable to a recent performance by London-based artist Barby Asante. In Declaration of Independence (Diaspora Pavilion, 2017 Venice Biennale), Asante appropriated the form of the UN assembly to host womxn of colour, inviting them to share narratives, memories and songs to a listening circle positioned before an audience. With Uddoh’s performance, the archaic technology of the scroll similarly affects the temporality of the news story; crucially, no dates are included in the transcript, suggesting that the audience are encouraged to draw connections between the various histories being chronicled. While Uddoh’s dragging of Stuart is prepared for by the surrounding screenprints, a second figure, one who is referenced obliquely in this exhibition, is perhaps closer in spirit to the pressure Auto Cutie exerts on the medium of the news broadcast.

[image9]

Of the three pencil drawings of Stuart included in the exhibition, two are embedded with the likeness of Una Marson (1905-65). Marson, a British-Jamaican feminist, writer and broadcaster, was employed by the BBC during the second world war to produce a radio show titled Call to the West Indies. During her tenor, she transformed its imperial basis by featuring Caribbean literature written in the metropole, renaming the programme Caribbean Voices. (Uddoh had figured Marson as an “imperfect colonial subject” in Black Poirot, a video work presented at Black Tower Projects, London, earlier this year.) As scholar Anna Snaith observes: “Marson’s shift from war propaganda to Caribbean Voices is highly significant; those radio waves which had been a vehicle for the dissemination of imperial ideology and British patriotism became in her hands conveyers of Caribbean cultural nationalism.”3 Her presence in the drawings introduces a history of anti-imperialist modernist practice that subtly informs Uddoh’s performance of Stuart.

In light of Marson’s legacy, what shines through Uddoh’s Stuart is a radical form of kinship that subverts our assumptions about centre and periphery, indicating the publicness that can subtend intimate forms of attachment. Returning the following morning, I find the scroll hanging like a washing line from the ceiling in long diagonal waves, revealing portions of text that create a dialogue with the surrounding prints and drawings. One of these, featuring both Stuart and Marson, is hung next to the sink underneath a shelf stacked with tea and sugar – the gallery space is located in a domestic setting. The two broadcasters gaze impassively outwards, their graphite figures separated on the picture plane, brooking a response.

References

1. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life by Sara Ahmed, published by Duke University Press, 2012, page 187.

2. See Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories by Elizabeth Freeman, published by Duke University Press, 2010. For an account of this strategy in contemporary art more broadly, see Fans of Feminism: Re-Writing Histories of Second-Wave Feminism in Contemporary Art by Catherine Grant in Oxford Art Journal, 34.2, 2011.

3. “Little Brown Girl” in a “White, White City”: Una Marson and London by Anna Snaith in Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, volume 27, no 1, spring 2008, page 109.