Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, Brazil

20 November 2014 – 22 February 2015

by CAROLINE MENEZES

The first exhibition of Australian sculptor Ron Mueck’s artworks in Brazil is on display at the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo (São Paulo State Picture Gallery), where the long queues of people have led the gallery to schedule extended opening hours. This touring show – which has now been seen by more than a million visitors – also enjoyed massive public appeal at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro last year, being the most visited individual exhibition in the museum’s history, with around 300,000 visitors in 40 days. Previously, it had great success in Buenos Aires at Fundación Proa and in Paris, at Fondation Cartier, where it had its premiere in 2013.

Having heard many comments about the blockbuster impact of this one-man show, and curious to check out the new set of artworks produced specially for it, I went to the Pinacoteca with some questions on my mind. What makes it so fascinating to look at the realistic reproduction of another human being? Why, throughout history, has observing a naturalistic representation of an inanimate “other” mesmerised so many people? I visited the solo exhibition of the London-based Mueck with high expectations, but also with some reserve. Is his success deep-rooted in artistic matters, or is it more related to this very human curiosity about lifeless artificial human models, as clearly demonstrated by the proliferation of wax museums around the world? In other words, are Mueck’s artworks really artistically alluring, or is his fame born from the same inquisitiveness that induces tourists to take photos next to mannequins representing celebrities?

Even the show’s curator, Robert Storr, critic and dean of the School of Art at Yale University, expresses this not uncommon feeling in a way in his text in Mueck’s catalogue: “Such considerations and such imagery tend to make sophisticated audiences infatuated by abstract ideas and forms cringe. It makes less sophisticated ones cringe too, mostly because they violate a sense of social decorum in a way now permitted in entertainment but still frowned on when it comes to art.”1

OK, I consider myself fond of abstract ideas, but not infatuated by them; nor am I someone who turns up my nose at anything in art, especially when that art has proved to possess an intrinsic connection with human nature, such as Mueck’s creations. However, I still cannot deny that the immense magnetism of his works seemed suspicious. Searching for understanding in Storr’s words, I found his explanation for what distinguishes Mueck’s artistic gesture: “The fundamental reason the man [the 2002 sculpture Man in a Boat] makes one uncomfortable is the same reason that we are embarrassed when moved by anecdotes or parables in 17th, 18th and 19th-century paintings – his likeness hits too close to home. Mueck has a knack for doing that. We should not blame the messenger in an effort to deflect the message, but thank him while each of us copes in his or her own way with the individual unease he triggers in us all.”2

So, as the curator says, Mueck has a special skill, a trick that induces us to recognise ourselves within his imagery. But when the same trick is repeated over and over again, in a loop, does it not lose its quality, or at least the element of surprise? After visiting the show, I would say that, in his case, the answer is no. His sculptures do have the potential to surprise the visitor by using the same skill in unexpected ways.

I first saw Mueck’s sculptures in 1999, when I was lucky enough to be visiting New York while the famous exhibition Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection of the Royal Academy in London was on tour at the Brooklyn Museum. This influential group show was Mueck’s gateway to the art world. By that time, the artist, who was born in Melbourne in 1958 and the son of toymakers, had dedicated himself to creating figures, dolls and puppets for the television and film industries, as for example the movie Labyrinth (1986), for which he designed visual effects characters to act alongside David Bowie.

In the New York Sensation show, I was overwhelmed when I saw hung on the wall the giant, disapproving face of the artist looking down at the visitor. This was Mueck’s first Mask (1997), an oversized frowning self-portrait that was very expressive in comparison with his later facial interpretations. Considering the many attractions that this special event had, back in those days, for me, a young, first-year art history student, the majority of the displays seemed dazzling. Among a shark in a tank by Damien Hirst, a frozen, bloody head by Marc Quinn, a Virgin Mary painting covered with elephant dung by Chris Ofili and other extravaganzas that YBA from the Saatchi Collection put together, lying on the floor, a half life-size impassive, naked man – Mueck’s sculpture Dead Dad (1996-7) – caught my attention. This emblematic figure particularly impressed me.

I have always thought that what caused this effect was perhaps the sculpture’s silence amidst the “chatter” coming from the other Sensation artworks. The peaceful, diminutive embodiment of death, through its simple and direct portrayal, became more powerful than the profusion of controversial subjects posed by the others. Many years and exhibitions later, what remained from this first encounter with the verisimilitude of Mueck’s sculptures was the impression that his artistic gesture was potent, but all the more striking, for being a quiet piece surrounded by dramatic artworks. Perhaps this was the main reason I have always had reservations about him, doubting the sincerity of his art. When I finally had the opportunity to see his solo show in Brazil, I realised that the poignant silence that emanates from his sculptures is actually the message he wants to convey, and not an effect of the contrast with the other “noisy” artworks. The mute communication is what makes each piece very honest.

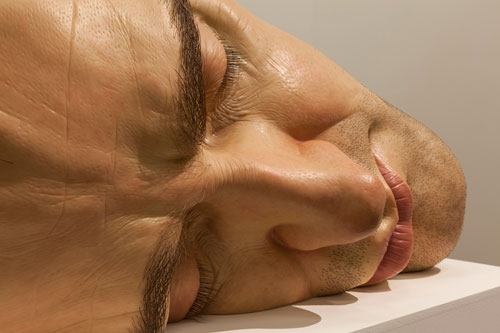

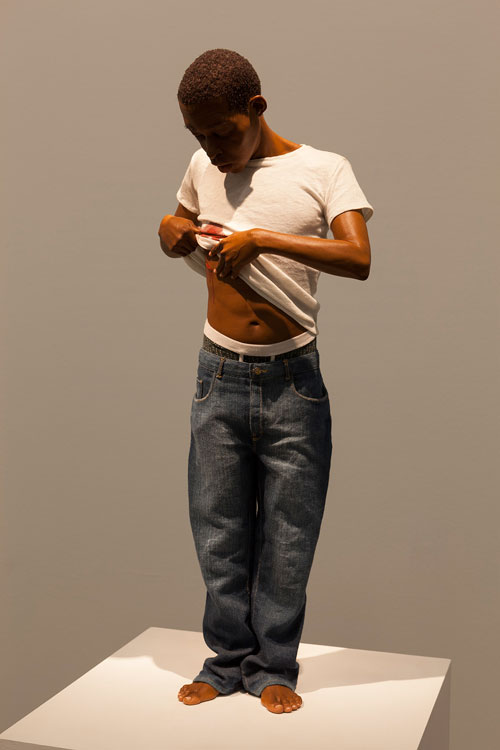

Silence is a compounding feature in his ability to faithfully reproduce the human figure with fibreglass, silicone or acrylic, and amaze people with disproportional representations of what is the most natural thing to see: other people. His work is detailed and he painstakingly covers his anatomically perfect, sculptured bodies with forged skin, including pores and hair. The faces are also veracious. However, they never express explicit emotions. The figures are everyday characters with subtle and almost inscrutable masks. The combined quantity and quality of the bodies’ minute details and small gestures speak loudly.

One example is Young Couple (2013), which could be a reduced image of a pair of teenagers one could encounter in any urban environment. But when one looks at the sculpture from behind, there is tension between the romantic pair; the boy is firmly holding the girl’s hand. Mueck’s characters seem to guard an unspoken secret. In Woman with Shopping (2013), the mystery resides in the hidden baby, in what is under the overcoat or in the bag. There are many elements to building a narrative that is never over. The smallest expressive gesture is the gaze that the baby directs at the woman, who strangely does not return the look.

Couple Under an Umbrella (2003) can be considered an installation. This time, the figures not only support each other, but also set an imaginary environment. By adding a single element – the umbrella – the old couple wearing bathing suits are transported to a beach, protecting themselves from the sun. The soundless body language between the pair is the amalgam that reveals their complicity. The stories the ageing skin and wrinkled faces carry remains private. The quietude of Mueck’s figures is the intriguing element that, in the curator’s words, “triggers us all”. The artist exposes every peculiarity of his models’ bodies, but never reveals the clamour of their possible thoughts.

Indeed, Mueck’s quietness is his practice’s distinguishing characteristic and also a personal attribute. He is known for being a reclusive artist, who does not enjoy talking in public or to the media. In the exhibition, the curatorship finds a way to introduce his personality to the visitors, with a film documentary that discloses his routine in the studio. Beyond presenting the technique, the documentary further emphasises the sensitivity, care – almost kindness – that Mueck devotes to his sculptures. In this sense, it highlights their particular resonance for our time. They are figurative sculptures that transcend appearance and converge in a human feeling of common solidarity and curiosity toward others.

References

1. Notes on Ron Mueck, London and Paris, by Robert Storr. In: Ron Mueck:

Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain, published by Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain Paris, 2013, page 114.

2. Idem