Roche Court New Art Centre, Salisbury

10 November 2018 – 13 January 2019

by JANET McKENZIE

The New Art Centre celebrates its 60th anniversary this year. The gallery, which opened in 1958 in Sloane Street, London, where Madeleine Bessborough sought to exhibit the work of young British artists, moved in 1994 to Roche Court, a 19th-century house in parkland near Salisbury in Wiltshire. In 1998, the architect Stephen Marshall built a contemporary sculpture gallery to link the existing house and orangery, built in 1804. As well as gallery spaces, there is an educational centre that is open to the public. The first sculpture park of its kind in the UK, it has work spread across 60 acres.

[image3]

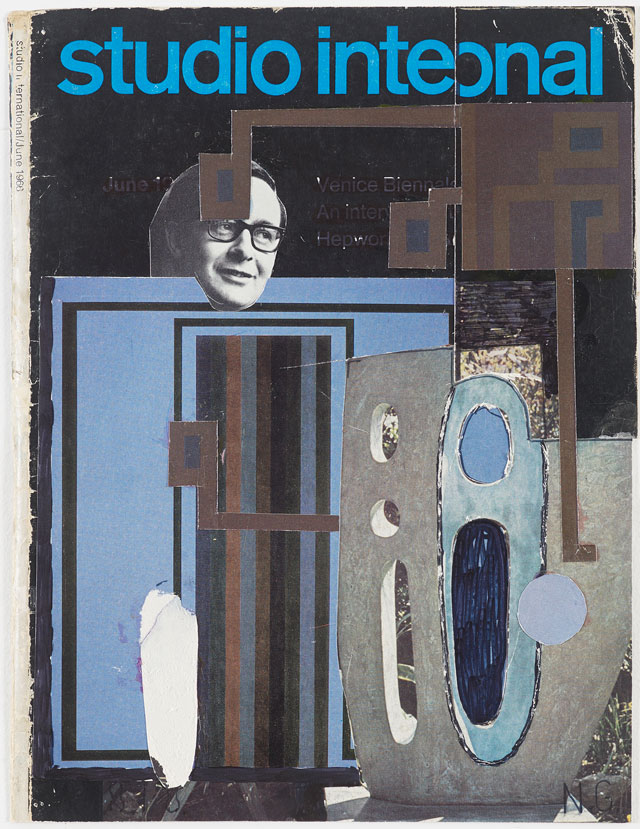

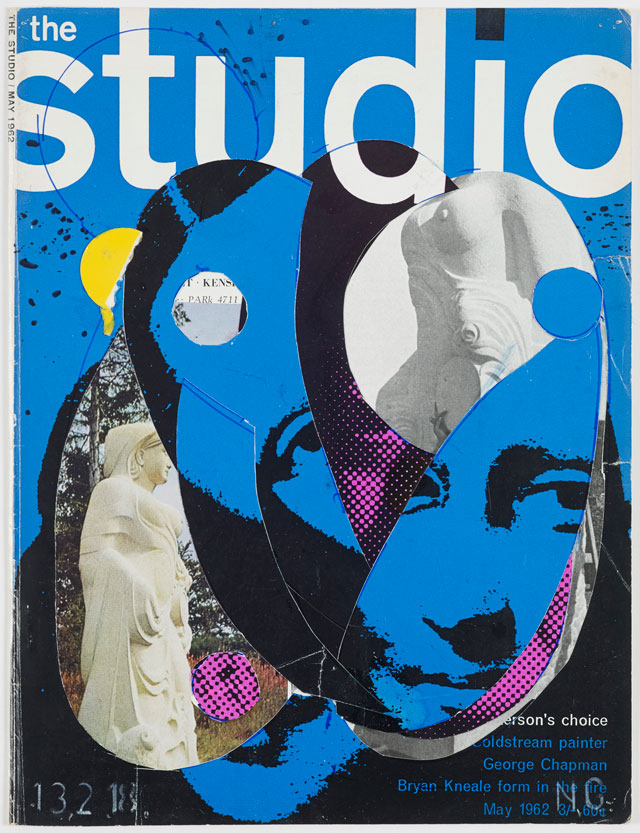

Currently showing are two exhibitions: Robyn Denny: Paintings from the 1960s and Neil Gall: The Studio – New Collages, Painting and Sculpture. These engage with Studio International on several counts. Bessborough was featured in The Studio magazine in a young dealer profile in 1962. The Venice Biennale: the British five (Anthony Caro, Bernard and Harold Cohen, Denny and Richard Smith), which roused great interest in 1966, was reviewed by David Thompson for Studio International and recently republished.

[image8]

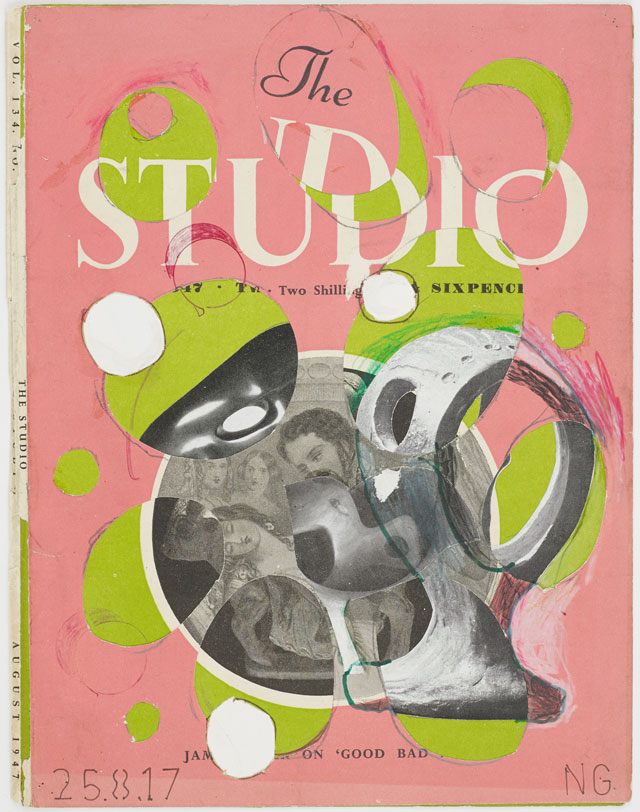

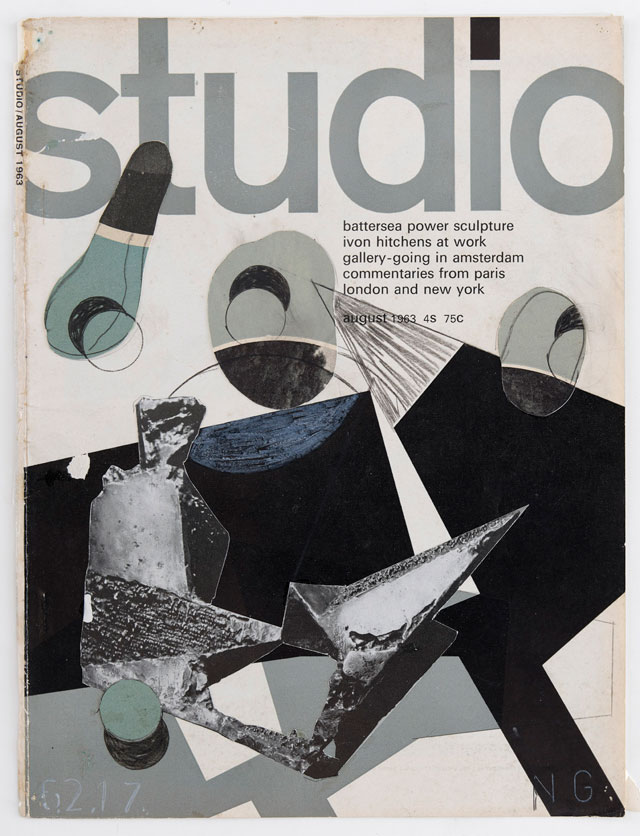

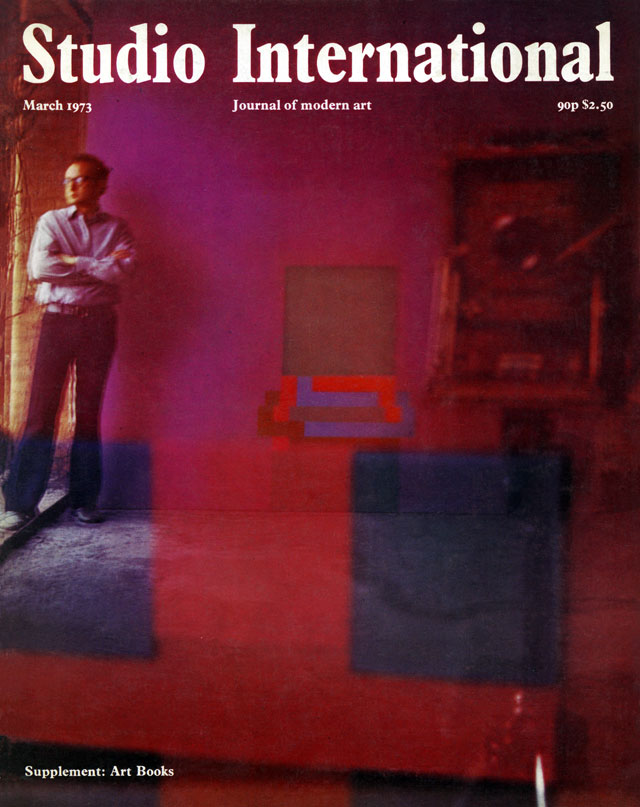

In 1973, Denny appeared on the cover of Studio International in a photograph of the abstract artist in his studio. This year, the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds exhibited work from Gall in which he used old copies of The Studio magazines as a departure point for collage and drawn forms.

[image15]

The unique exhibition spaces at Roche Court, under the skilful charge of director Stephen Feeke, lend a contemporary take to the abstract art of the 60s. Far from being nostalgic, the Denny exhibition prompts visual dialogue between the architectural space, the paintings themselves and the viewer. The gallery that links the house to the orangery was always conceived as an indoor / outdoor space. It is primarily a sculpture gallery (although painting exhibitions are regularly staged) and it is designed so that the hang can be viewed in its entirety from outside, before one enters and views each work in sequence through a hallway with shallow steps. From outside, the viewer observes the works through glass that reflects the park and the constantly changing effects of light. Inside the long narrow space created from stone and glass, the outside world is always present.

[image7]

Feeke describes the gallery space as giving form to the theatrical notion of the “fourth wall” that exists between actors on stage and the audience: “It is the effectiveness of the actors to break the fourth wall, in order to connect with the audience, to enable them to imagine what is taking place.” In theatre, no such wall actually exists, and in Marshall’s architectural space it is the glass wall that plays an important role in the manner in which we view the work – in this case, eight large works by Denny. In the next room, the orangery, there are collages made by Denny in the 60s that glow in their intensity, fine compositions in themselves that also elucidate the artist’s creative process.

[image4]

In the Artist’s House (a further modern addition, completed in 2001), Denny’s small, unglazed collages create a connection to the second exhibition, Gall’s works using The Studio magazines as a departure point for collage and drawn forms. Gall’s innovative drawing methods embrace sculpture, a form of spatial drawing. At a sculpture park with Denny’s geometric, architectural works of the 60s, they create a dynamic alignment of spatial perception spanning 60 years.

[image12]

In the interview for Studio International, this summer, Gall observed that, being mostly a black-and-white publication, The Studio could reproduce sculpture more effectively than it could painting. The Studio was therefore instrumental in informing its international readership about British sculpture, thus enabling the careers of Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore et al to flourish. The connections between sculpture and British art in the 20th century, the history of public and commercial collections and the spatial connections between architecture and sculpture, spatial drawing and the environment in the 21st century are intuitively conceived in the exhibitions at Roche Court and there is an air of serendipity as one moves from one gallery space to the next.

[image5]

Denny’s hard-edge, architectural canvases suggest portals, gateways, an entry point to contemplative states of mind, the future and the unknown. His work was inspired by the New York School and was deeply felt when, at the 1958 Venice Biennale, a year after he completed his studies at the Royal College of Art, London, the young artist experienced the immersive mobilisation of self, surrounded by a room of paintings by Mark Rothko. In the absence of elements from the real world (such as collage and stencilling that Denny used in the 50s), Rothko’s sensory interaction enveloped the viewer. In the 60s, the experience of art was intended to be a metaphor for the participation of the individual in modern society.

[image2]

Denny liked his works to be hung low, indicative of a doorway, and at Roche Court this is done to great effect. The hang along the wall of the gallery space does not surround the viewer as in the Rothko exhibition in Venice in 1958 or the Rothko installation at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Los Angeles in the 80s. Instead, elements of nature, and particularly the changing effects of light, play a key role in what is an essential 21st-century conversation. Roche Court’s presentation of Denny’s mysterious and enigmatic 60s paintings allows the viewer to embrace the art within the manmade architectural space and to observe its interaction with the environment. The impact of Denny’s canvases on the psyche is still direct, but one is made aware of the physical world and the relationship that we as its citizens must assume to reverse environmental destruction.

[image6]

Denny was a leading British abstract artist in the 60s and 70s, a period that saw the transformation of British art. Born in Abinger, Surrey, in 1930, he studied first in Paris, then at St Martin’s School of Art (1951-54) and the Royal College (1954-57). He represented Britain at the 1966 Venice Biennale, and in 1973 was the youngest artist to be given a retrospective at the Tate. Denny reacted to traditional British landscape paintings and to the gloom of the postwar years by turning his back on European art, finding American culture more immediate and relevant. He was one of the first British artists of the postwar years to take his influence from American abstract expressionism, which he saw at the 1956 Tate exhibition Modern Art in the United States, with works by Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko. Denny’s vast canvases in response to the American artists were shown at the important 1959 exhibition Place at the ICA; the canvases formed a maze in an early site-specific installation and viewers were encouraged to become participants. In 1962, the Arts Council touring exhibition Situation travelled to Cambridge, Aberdeen, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Bradford, Kettering and Liverpool. A celebration of the large canvas of modern life, it was comprised entirely of abstract works of not less than 30 ft square. Denny exhibited three large canvases. Art historian David Alan Mellor described Denny’s work as some of the most accomplished abstract paintings made in Britain in the 20th century

From 1981, Denny lived in Los Angeles, where he absorbed the powerful influences of abstract expressionism and the pop art movements, particularly admiring the work of Rothko, Barnett Newman and Ellsworth Kelly. His aesthetic developed further in the urban environment there. He returned to England in the early 90s and was included in the 1993 exhibition at the Barbican, The Sixties Art Scene in London. This show revived interest in his work and he held several solo exhibitions. He died in France in 2014. It is deeply satisfying to revisit the abstract work in the present climate and to contemplate its importance for the future.