Musée d’Orsay, Paris

6 November 2018 – 27 January 2019

by ANNA McNAY

Walking into the side galleries in the impressive Musée d’Orsay, Paris, on a wet and windy late-autumn day, there is suddenly the feeling of spring – a girl laughs as she gaily swings back and forth, and a young couple promenade, doe-eyed, enjoying the first throes of young love. In black and white, these scenes play out on a loop on a large screen – extracts from some of the best-known and best-loved early films by the French film director Jean Renoir (1894-1979), while, on the surrounding walls, colour luminesces, as the same – or very similar – scenes are frozen, like screen grabs, on the canvases of his father, Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), the impressionist painter.

[image8]

And so it goes on for the duration of the exhibition, which fills the galleries along the length of the first floor of the museum: Renoir-father and Renoir-son interspersed and in conversation – repeated motifs, repeated scenery, repeated models. The idea is not to place Jean in his father’s shadow, but to explore the extent to which his father’s legacy, and their close relationship, with Jean’s intimate understanding of his father’s painting process, influenced his directing career – either in terms of deliberately paying homage to, or deliberately seeking to move away from, such ascendancy. As Jean said towards the end of his career: “I have spent my life trying to determine the extent of the influence of my father upon me,” going on to describe his ambivalence and the periods “when I did my utmost to escape from it to dwell upon those when my mind was filled with the precepts I thought I had gleaned from him”.

Of course, the exhibition also goes further and explores the points of intersection between painting and cinema and the potential of the moving image to expand on the seemingly spontaneous snapshots of everyday life, captured by Renoir-senior, which have come to epitomise the quintessential French tradition of life à la campagne.

[image7]

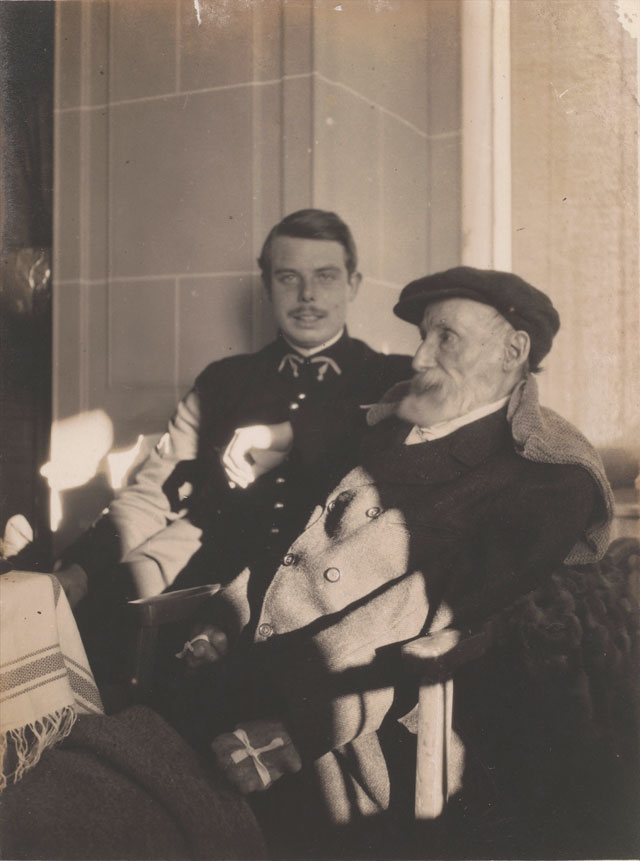

Pierre-Auguste Renoir spent the final years of his life on the family estate of Les Collettes, in Cagnes-sur-Mer, on the French Riviera. Jean returned there following a war injury (he received a bullet in his leg and was left with a permanent limp), and spent a lot of time with his ageing father, helping him, despite his father’s crippling rheumatoid arthritis, to hold his brushes and continue to paint. Jean already knew his father’s process inside out, having frequently been used as a model when he was a child.

[image13]

Between 1895 and 1910, he was the inspiration for about 60 paintings, drawings and pastels, initially with his nanny, Gabrielle Renard, then later alone. Many of these portraits are on display here, including the somewhat twee Jean Renoir Cousant (Jean Renoir sewing) (1899-1900), in which he reluctantly sports long, golden curls, which, despite his being teased for at school, he was compelled by his father to retain uncut until the age of seven. In later life, Jean recalled sitting for this portrait, and how Renard gave him a dress to stitch for his toy camel, which kept him virtually motionless for long stretches of time. A later portrait, Jean en Chasseur (Jean as Hunter) (1910) recalls Diego Velázquez’s grand portraits in the Prado, Madrid. Jean kept this painting all his life and, in his film La Règle du Jeu (The Rules of the Game) (1939), cast himself in a scene en chasseur.

[image6]

Renard was a very significant figure in the Renoirs’ lives. Following the death of Madame Renoir (the painter’s former model, Aline Charigot), from a heart attack in 1915, she took over the maternal role for Jean and his brothers. Two paintings of Renard and Jean capture such intimate domesticity, with one depicting them playing with animal figurines. Two portraits of Renard alone are, for me, some of the most beautiful paintings in the exhibition, glowing with warmth and tenderness, a familiarity perhaps not so present in paintings of less well-known sitters.

[image10]

In later life, Renard moved to Los Angeles to help Jean, by now directing movies in Hollywood, rekindle his memories of his childhood and his father, as he wrote the moving and affectionate biography-cum-autobiography, or, as the film critic Serge Toubiana termed it, “ciné-livre”, Renoir, My Father (1962). Notebooks containing ideas for this work are shown alongside filmed interview clips with Jean and a photograph of father and son, from around 1916, attributed to fellow artist and family friend Pierre Bonnard.

Both father’s and son’s first artistic experiments were with ceramics: Pierre-Auguste worked as a porcelain painter, and Jean, as a child, was encouraged to “make something with [his] hands” using the kiln his father had installed at the family estate. Between 1919 and 1924, Jean produced, exhibited and sold ceramics – some of which are on display here – and he later compared the ceramic process to the cinematic, suggesting both involved an element of chance. A painting by Albert André, Jean Céramiste (Jean Ceramicist), from 1920, shows Jean at work on his pots.

[image5]

Renoir’s final model, Andrée Heuschling, nicknamed Dédée, was also a frequent presence at Les Collettes. As well as sitting for him, she also helped the artist in this time of ill health. In January 1920, shortly after his father’s death, Jean and Dédée were married. Both were enthusiasts for contemporary American cinema and Jean later claimed: “I set foot in the world of cinema only to make my wife a star.”

[image12]

Now known by the stage-name Catherine Hessling, she took the lead role in his first feature-length film (La Fille de l’Eau/Whirlpool of Fate, 1925) and four further films. She was more than just his muse and lead star, however, taking an active role as artistic partner, and with her expressionistic character dominating the screen, especially in Charleston Parade (1927). Clips of these films are captivating, although better seating options in the galleries would make one more inclined to sit and watch them through. In 1931, Jean excluded his wife from his new project, The Bitch, and they separated.

[image15]

Heuschling was also the model for what is described as one of Renoir’s most important late works, Les Baigneuses (The Bathers) (1919). Painted in oil, it nevertheless has the appearance of pastel, so gentle and blended are the colours. With its integration of figures into the landscape and fleshy sculptural form, Jean described the painting as the “testament artistique” of his father. There is something about the serenity of the work that brings to mind the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

[image4]

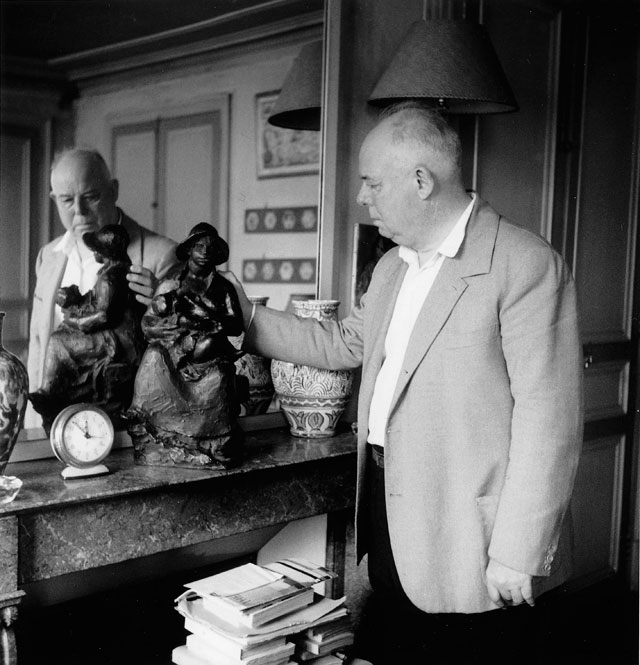

After eight years making films in Hollywood, Jean returned to France, where he worked as a director from 1953-56. During this time he was commissioned to write and direct two films set in the Paris of the belle époque – French Cancan (1955) and Elena and her Men (1956) – both of which offer a kind of homage to his roots in the impressionist world of fin-de-siècle Montmartre. Having sold the several hundred works by his father, inherited on his death in 1919, to fund his career, Jean was, by now, gradually buying them back. However, their value, in the meantime, had rocketed, so his reacquisitions were largely modest in scale. This search to rebuild the surroundings of his childhood evidences the fact that, all too often, what in youth we think we want to escape, in adulthood we want to bring back close.

[image2]

One of Jean’s final works, Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe (Picnic on the Grass) (1959) (the nod of the title – to Edouard Manet’s post-impressionist painting – not going unnoticed), was shot on the family estate of Les Collettes and features the old, gnarled olive groves, so often painted by Renoir, and the dark-haired character Nénette is certainly reminiscent of Renard. There is a prevailing sense of living in and for the moment, shared with many of Renoir’s final paintings. “For our peace of mind,” Jean said late in life, “we must try to escape from the spell of memories. Our salvation lies in plunging resolutely into the hell of the new world.” He never made another film in France and spent the final 20 years of his life in the US. And yet, it is his works in which his memories so vividly come to the fore that one feels most absorbed and by which one is most convinced and impressed. The legacy of our parents becomes part of the legacy of ourselves, and the works of these two generations of great artists – painter and film director respectively; father and son – presented here in conversation, weave a wonderful new and absorbing story of their own.