Chisenhale Gallery, London

24 February – 23 April 2023

by TOM DENMAN

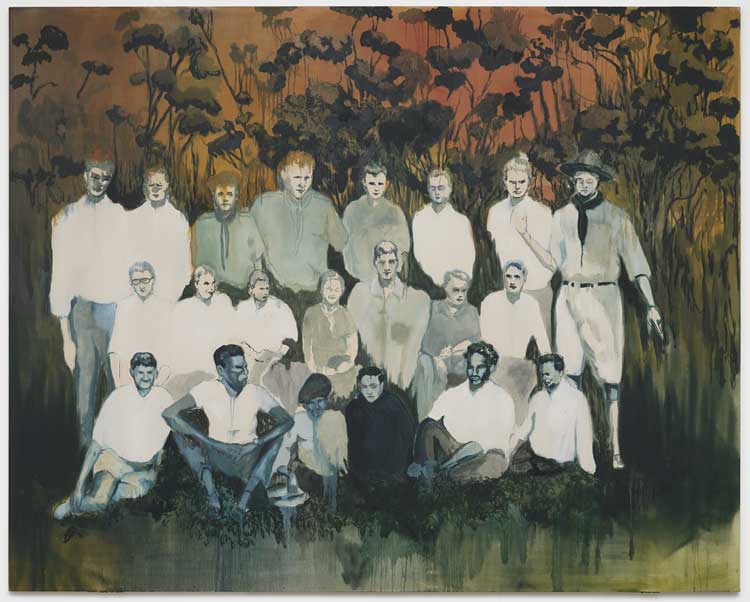

They pose in the ranked format of group photographs, rendered in an overexposed monochrome that glimmers with the passing of time. On first glance, we know that The Instruction (A gathering of friends) (2022) is a painting about history, the essence of which is carried in its reference to the documentary medium of photography, while its washed-out quality is also suggestive of memory. The figures oscillate between distance and proximity. Some are unnaturally small or large, isolated as well as unified with the others. Around the group, in thinly applied orange, green and yellow oil, is a jungle setting, which could almost be a backdrop in a photographer’s studio, except it envelops the figures, acting more as a mental cloud – up in the air, invisible, imagined. As a whole, the picture has a collage-like quality that artfully contradicts itself, as the components are both separate and blurring into each other. It does not strike as an obedient copy of a single image, though there is a sense of something being reclaimed – as if the figures were being remembered photographically, with recall mimicking archival record in paint.

[image11]

In the postcolonial imaginary, the type of photograph this painting references is part of the visual language of imperial violence: white people brandishing their dominance, in this case euphemising it through a semblance of bonhomie. Although ostensibly benign in comparison to many such images, the figures on the lowest rung have darker complexions and hair than those occupying the two rows above, all of whom are white. To the right of the group, a white man in a hat gestures awkwardly with one hand pointing down and the other raised, as if by moving his arms he could maintain the social hierarchy – which, along with the signifiers of race, has yet to fade from view.

[image10]

The Johannesburg-based artist Ravelle Pillay descends from Indian workers who came to South Africa during the period of indenture, when millions migrated from India to the European colonies to fill labour shortages that resulted from the abolition of slavery in the 19th century. This system of contracted servitude was very much abused, despite the declared freedom of the labourers, leading to a definitive ban on the British empire’s use of it in the 1920s. Based on images found in personal and colonial archives, Pillay’s paintings have a washy tranquillity beneath which violence lurks, seeping to the surface as if by capillary action, or perhaps in the way photographic images form when light, chemicals and memories mix. They warrant comparison with photography not because they are photorealist in style – they are not – but because they embody a photographic referentiality that locates them in a specific time and landscape (and yet specificity is also destabilised by her application of the paint), from which they diffuse into the present. Links could be made with canonical painters such as Marlene Dumas and Luc Tuymans – who also make out-of-focus, reality-questioning adaptations of photographs – but by exploring a particular historical and archival context that is personal to her, Pillay freshly contributes to this intermedial dialogue.

[image12]

The images may make us curious about their sources – The Instruction (A gathering of friends) is based on a photograph of people Pillay’s grandfather knew posing with officials from the Scouts’ Association, she reveals in an interview with the curator, Olivia Aherne – but they all withhold this information. Their power lies in their painterly deviation from it, in the implication of a possible source. In another group “portrait”, Victory (flesh that weeps) (2023), men in sport vests are holding gold cups. On either side stands a figure in indigenous Fijian clothing (Fiji was another place to which many indentured Indians were sent), positioned, it would seem, for ornamental purposes – not unlike the landscape in the previous example. The team is multiracial, and mostly, if not entirely, non-white, while a white man squats at the front and smiles at us. He is distinguished from the rest, in a white suit, squatting in that familiar, always momentary way, ready to spring back up again. The only person sharing his joyful expression is the one nearest to him, as if he were nudged. Who the real winners are is hard to tell, as dispossession and displacement, seizure and servitude underlie what is ostensibly a picture of glory. Dismantling the unidirectionality and fixity of the colonial gaze, Pillay sets in murmurous motion the possibility of multiple perspectives and the psychological ambiguities that riddle them.

[image6]

Pillay’s approach is subtle, as she brings the emotional process of finding, selecting, examining and recreating these perplexing, painful images to manifest unforcedly in the paint. And in all this, including also the acts of looking and describing, a colonial hauntology is ingrained. This spectral elusiveness is felt especially in her landscapes, which on the surface seem innocent enough, although they, too, translate the aura of the colonial archive, no less violent for not centring on human subjects. There Is Water at the Bottom of the Ocean (2023) depicts a murky shoreline against jungle, the scene empty of figures. Neither an advertisement for the tropics – the sky is underpainted in a dirty nicotine – nor an image of reverence towards nature, the painting refuses to appease us (unlike the work of Peter Doig, to which Pillay’s could be seen almost as a rebuke). It consists of layered stains and abrasions: an original has been meddled with; it secretes the damage that it itself has inflicted, as if diseased. Covering much of the bottom right of the canvas is an opaque, greyish green that resembles a superimposition or reflection of something, possibly a waterfall. This spectral abnormality denies access to, while also providing awkward contact with, the scenery, with its sounds and wetness.

In two paintings hung back-to-back in the middle of the room, The Drowned (hold your breath) and Cold Water (the undrowned) (both 2022), a white gash of a waterfall opens amid darkroom-red rocky terrain. The explosion of white vivifies the sounds and freshness of the water, while the redness is suggestive of the cold harshness of record. In the former, the water is sharply delineated, its destination seemingly invisible, the tightness of the landscape preserved by the clothed comportment of the figures; whereas in the latter, the people are swimming, the landscape is more varied, and we see the white water crashing into the pool. If the swimmers are indentured workers enjoying a moment of freedom (as I am inclined to see them), such freedom is contained.

[image8]

In Chorus (2023), a luscious wreathlike portal consisting of various species of plant gives way to a strange, bleeding landscape beneath a break in the clouds. This apocalyptic background is the closest Pillay gets to the sublime – possibly alluding to colonial visions of the “other” – except it is difficult to tell whether the land is overpowering or overpowered. The botanical framework, relatively neat in its delineation, resonates with the colonial itemisation of exotic organisms. In this way, Chorus speaks to the series of Indian ink drawings of tropical vegetation, also in this show, which are on translucent acetate to prop up its overall theme of reduplication and alteration. It is a strange thing, describing Pillay’s work, because, of course, the compositions are not exactly hers. Instead, she reappropriates her sources as target of critique and point of reference to explore the swampy and amorphous, contradictory zone of historical memory. Running drips reminding us that – contrary to the illusion of (printed) photography – nothing is ever fixed.