Hauser & Wirth, New York City

8 September – 22 October 2016

by MATTHEW RUDMAN

Hauser & Wirth 18th Street is not a venue for the faint-hearted: the 23,000-square-foot former roller-skating rink poses a formidable challenge to artists tasked with showing their work in the cavernous space. It is no small wonder, then, that Fly Away, Rashid Johnson’s latest exhibition, brings the gallery back down to a more human scale.

The exhibition’s title is taken from the 1929 gospel hymn I’ll Fly Away, a song that has been revisited again and again by artists from Aretha Franklin to Kanye West; the phrase presents an interesting spin on Johnson’s work, concerned as it is with questions of personal and group identities. Johnson, who was born in 1977 in Chicago, rose to prominence in 2001 at just 24 years old when his work was selected by Thelma Golden to appear in the exhibition Freestyle at the Studio Museum in Harlem. That exhibition is credited by some to have popularised the genre term “post-black art”: art, by a younger, post-civil rights generation of artists, that seeks to explore diverse notions of black identity and culture while avoiding the restrictive label of “African-American artist”.

Wikipedia’s editors use Johnson’s work to illustrate the genre, but the artist himself is ambivalent about the term, remarking to Artspace in 2013: “It’s a term that people are very much confused by. I count myself as one of those people. But I don’t find it to be terribly problematic.” Starting out with photography as his primary medium, Johnson has since explored collage, sculpture and large-scale installations, often using Afrocentric materials such as black soap, shea butter, ceramic tiles and burnt wood.

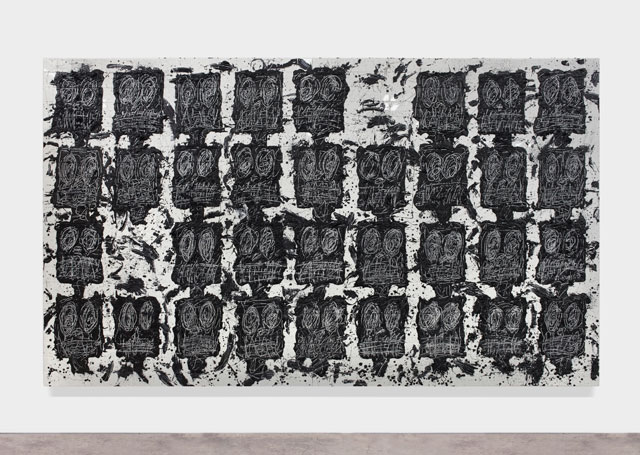

Johnson has divided the gallery space into four discrete zones, each housing a different series of works. Visitors arrive in the largest room, populated by six new pieces that form part of the artist’s Untitled Anxious Audience series. Large (two by four metre) slabs of white ceramic tile are daubed with black soap, into which frazzled, worried faces have been scratched. Johnson has previously shown these faces individually, most recently at the Drawing Center, New York in 2015. Here, however, he has multiplied them into four rows of nine. We are faced with a crowd of anonymous black faces, with the occasional face missing in some panels.

Metaphorical meanings jump out at the viewer: are these nervous black crowds the artist’s projected audience rendered in soap on tile? Could they be a reference to the racial tension that has boiled over in the US over the past year? These works do not dictate a concrete meaning or message, engendering claustrophobia and anxiety on the part of the visitor, despite the vast scale of the room.

From here, we are drawn on to the show’s standout piece, the monolithic Antoine’s Organ. Within a cuboid structure of black scaffolding, Johnson has interspersed various objects such as plants, shea butter, ceramics and screens showing video work. Books are laid down in piles on Persian rugs, the majority of which address the African-American experience in society, both historical and current: The Souls of Black Folk by WEB du Bois, Sellout by Randall Kennedy, the similarly titled The Sellout by Paul Beatty (on this year’s Man Booker prize shortlist), and Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates. In the centre of the assembly, barely visible through verdant foliage and striplights, is an upright piano, on which pianist and producer Antoine Baldwin, also known as Audio BLK, plays original jazz compositions intermittently.

Antoine’s Organ feels like a culmination, as if Johnson has gathered the exhibition’s various threads and funnelled them into one carefully curated bricolage. This isn’t the first time he’s used this technique – his grid-based sculptures have been shown in Garage Museum, Moscow (2016), the David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles (2014), and on New York’s High Line park (2015-2016). However, this is the first time that he has exhibited such a structure in the US on such an impressive scale.

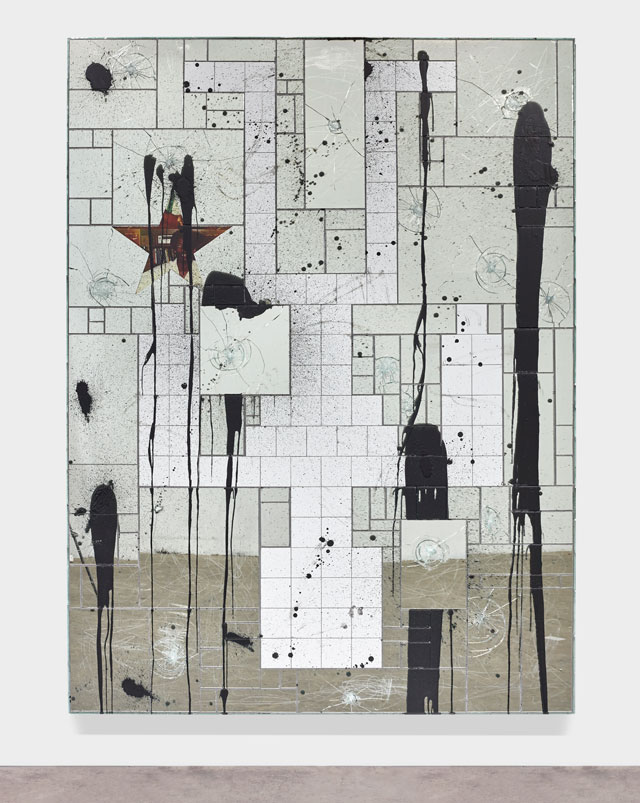

After being lifted up to Hauser & Wirth’s high ceiling, visitors will be taken back down to earth in the next room, which contains three pieces from Johnson’s Falling Men series (2015) and a sculpture, Untitled (shea butter table) (2016). The Falling Men panels show inverted eight-bit humanoid shapes falling – or flying – against a background of geometrically-broken glass or seared wood.

Johnson’s signature materials are on show here: not only mirrors and branded wood, but plant life, splashes of black soap, cut-up photography and, in one of the objects, a small bookshelf on which has been placed Black Bolshevik, the autobiography of African-American communist Harry Haywood. In the centre of the room stands a table, seared with circular brands, on which is draped a Persian rug and great slabs of yellow shea butter. It is at once an artist’s worktable for the shea butter dispersed throughout this exhibition and an altar for precious non-western resources. Once again, wild social and political interpretations are invited, but never explicitly anchored.

Untitled Escape Collage (2016) is perhaps the most intriguing of the three series of works on show: here we see a bathroom tile base that is familiar from Untitled Anxious Audience, but these tiles are alternating in red, gold, black and grey. On to this base, Johnson has spray-painted stencils in geometric patterns, while tropical wallpaper scenes are pasted on in diamond shapes. Dribbling splashes of black soap overlap slashes of gold spray paint, evoking sanitised subway grime. The overall effect is a brilliant mess, a strange mingling of the bright and exotic with the urban and grubby.

Of Untitled Anxious Audience, Johnson has remarked that they represent “the culmination of all [his] tile paintings, the final chapter of this body of work”. One wonders whether the same could be said of the other works on show here, which use techniques and materials Johnson has worked with and perfected over the past few years. At Hauser & Wirth 18th Street, we can see Johnson at his best, assembling and casting a wide net of referents and signifiers, waiting to see what his audience makes of it.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)