Alexander Calder: Calder Lightness

Fred Sandback: 64 Three-Part Pieces

Richard Tuttle: Wire Pieces

Pulitzer Arts Foundation, St Louis

1 May – 12 September 2015

by LILLY WEI

There is now a sign of noticeable, if not flagrant, size outside the entrance to a building much admired for its precise measurements and interior, light-cradled serenity, anchored by two iconic works on permanent view, by Ellsworth Kelly and Richard Serra, one indoors and the other outdoors. (A Brancusi could be glimpsed through the glass window of an upstairs office.) The sign identifies the elegantly aloof building as a museum, and announces the three exhibitions currently on view – Alexander Calder (1898-1976), Fred Sandback (1943-2003) and Richard Tuttle (b 1941) – celebrating a re launch that is not only architectural, but also philosophical. In a more outgoing mode, the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, built in 2001 by Tadao Ando, the revered master of understated refinement, has not only undergone a renovation (its first), but is actively seeking larger, more diverse audiences, hence the sign. Before, many of its neighbours didn’t even know that it was a museum, or that they were welcome to enter. And with the sign also comes an ambitious, multi disciplinary programme, the doubling of its gallery space through the addition of 3,700 sq f t (344 sq metres) to its lower level, extended hours, and a new director, Cara Starke, formerly of Creative Time in New York.

Inside, Calder’s sculptures are installed in the original galleries, an exhibition guest-curated by Carmen Giménez (who presented an acclaimed Calder exhibition at the Guggenheim in Bilbao in 2003). A luminously beautiful exhibition that seemed destined for this space, it consists of mobiles, stabiles and wall pieces, each so exceptional that to say the whole was greater than the sum of its parts in no way diminishes those parts, but simply praises the impact of the ensemble. The varying of the scale, colours and shapes of the sculptures was sensitively and adroitly choreographed, their vibrant interaction felt as much as seen. Together, they form a galactic system of sorts, a constellated cosmos that shifts subtly as the mobiles turn, as the eye travels from point to line to plane, the still and the moving, as if the viewer was beamed up among the stars. The sense of fluidity, of cinematic drift, is enhanced by the flickered light streaming in through the windows and reflecting off the channel of water that edged the exterior of the gallery, the inside and outside seeming to merge. While Calder has long been in the pantheon of great American artists, it is exhibitions such as this one that remind us why.

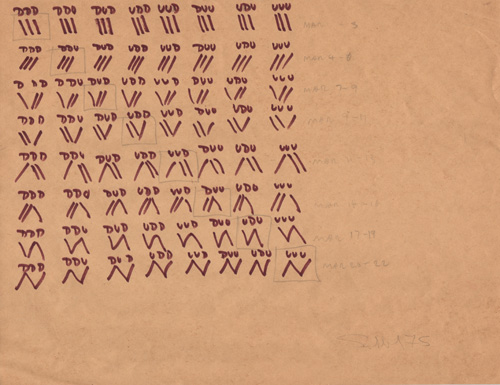

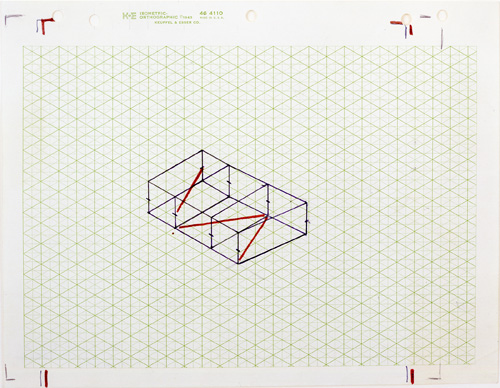

Fred Sandback and Richard Tuttle were installed below, in the new galleries, warmed by the honeyed glow of wood floors. Sandback’s brilliant early series 64 Three-Part Pieces debuted in Munich in 1975, although only six of the configurations were shown then. Curated by Tamara H Schenkenberg of the Pulitzer, 20 of the 64 combinations will be mounted during the run of this show, changed on a weekly basis. The accompanying drawings of all 64 possible variants, plus some preparatory sketches, give an idea of the full extent of the project as well as a glimpse into the artist’s thinking and process. As with any Sandback installation, it is precise, governed by the artist’s specifications – three separate lengths of red-brown yarn stretched tautly across three adjoining spaces on a diagonal at a height of 150 cm or across the floor, bisecting the room, shown one at a time. However, Sandback also factors in the site, the length of the yarn varying in accordance with the dimensions of the venue, the materiality of the yarn itself yielding slightly different results, underscoring the fallibility of human endeavours and its inability to replicate exactly (unlike mechanical and electronic devices ). The planes that he creates out of nothing construct a kind of magical architecture, a tribute to perception, to what we see and what we think we see, as well as to what he once called “something after the fact” – a something that might be art.

Richard Tuttle’s Wire Pieces, conceived in 1972, is curated by Emily Rauh Pulitzer, and is another exhibition that is based on transforming two-dimensional line into the sculptural, capturing and modelling space. Tuttle, known for his keen interest in materials and his attentiveness to their essential properties, is showing 14 of these works. Installing them himself is a requisite, the works almost making themselves in collaboration with the artist, existing in this manifestation only in this space; once de-installed, they vanish, a cycle of ephemerality and recurrence that intrigues him. Another utterly satisfying show, perhaps one of his most perfect due to its intimacy, immediacy and focus, you sense the artist’s hand in a three-fold reiteration: drawing in pencil directly on to the wall from preliminary sketches; tracing that drawing with a florist wire that is affixed by little nails, then cut or otherwise altered and left to find its own configuration, its own state of equilibrium; and following the shadow cast by the wire, “drawn” by lighting carefully directed by the artist. Fragile in appearance, vulnerable, they are curiously touching, emotional. As in Sandback’s series, it is not so much that less is more, but that simplicity becomes rich, complex.

These three complementary projects by three great American artists, grounded in the phenomenological, the conceptual or both, were a rare pleasure to behold. If you happen to be in St Louis, don’t miss them.

.jpg)