Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

15 July – 27 November 2022

by BETH WILLIAMSON

This show of pre-Raphaelite drawings and watercolours is a welcome reprise for a beautiful exhibition that was, sadly, cut short after just five weeks in 2021, due to the pandemic. The Ashmolean’s renowned collection of drawings and watercolours by pre-Raphaelite artists is normally held in its Western Art Print Room. On display here in the galleries at the top of the museum is a wide range of fragile and tender works rarely seen together. From intimate portraits to studies for paintings and commissions, as well as landscapes and historical subjects, this very personal exhibition is a delight.

[image8]

The pre-Raphaelites, including John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, resolved, in 1848, to rebel against the academic form of teaching at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. They believed in a new and forward-looking model for working that intended to depart from the mannered style of artists who followed Raphael. Known as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), they aimed for an approach to painting that was both authentic and original. To do this, they attended to nature, took inspiration from the art and poetry they admired and from their friends. They loved to make affectionate drawings of each other as well as their friends, families and patrons. Animals were not excluded and the exhibition includes the delicate and thoughtful Study of a Greyhound (1852-65) by Ford Madox Brown. This reappears in the painting Work (1852-65), which exists in two versions. The PRB’s early activities were supported by Thomas and Martha Combe, important patrons who hosted the young artists and bought their work. The couple’s collection of pre-Raphaelite works was bequeathed to the Ashmolean on Martha’s death.

[image2]

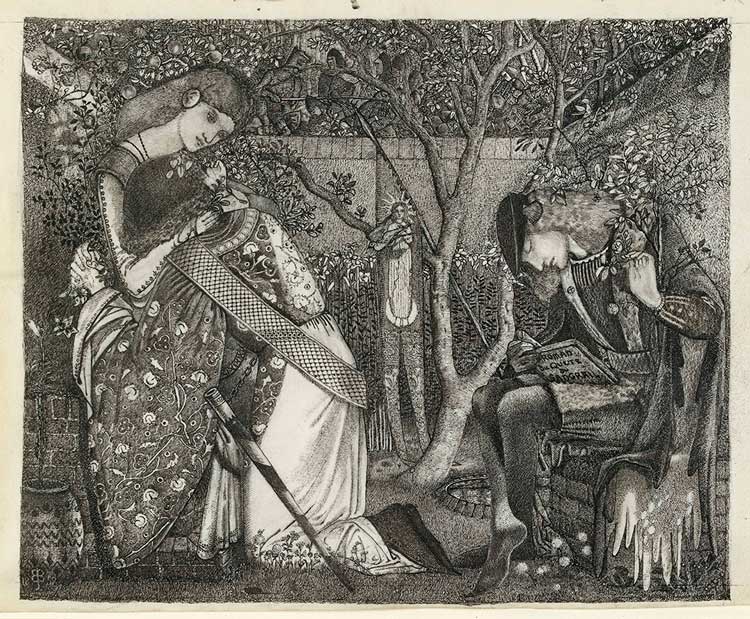

The variety of drawing styles is vast, even in the work of an individual artist. Edward Coley Burne-Jones, we are told, loved to experiment with different materials and that is evident in the works on show here. In the achingly tender Study of a Woman’s Head, Turned to the Left (1868), he used heavy textured paper and black and red chalk, rubbed lightly on the surface of the paper to create an array of colours. This is very different from the detailed penwork of earlier drawings, such as The Knight’s Farewell (1858) which shows incredible detail using minute pen strokes on vellum.

[image3]

I was intrigued to discover that the term “stunner”, for a strikingly beautiful or impressive person or thing, was coined by Rossetti who used it to refer to art and poetry, and to his models. However, rather than focusing on conventional notions of feminine beauty, Rossetti often depicted his models alone, or deep in thought, indicating a profound inner life. They were shown in loose flowing clothing rather than the tight-fitting corsets and crinolines of convention. Elizabeth Siddal, who sat exclusively for Rossetti from 1851, is repeatedly shown deep in thought. Jane Morris, another of his models, is depicted in the flowing lines of Icelandic Costume (c1873) and, in another drawing, reading a newspaper (c1870), neither of which was in keeping with conventional depictions of female models.

[image4]

Many of the drawings in this exhibition are works of art in their own right. However, an entire section is devoted to preparatory sketches and studies, often the precursor to a painting, an item of furniture or even a stained-glass window. The beauty of being able to see preparatory works is that it gives some insight into how an artist’s ideas developed. There are beautiful Designs for Decorative Lunettes (1847) from a very young John Everett Millais. Burne-Jones’s Studies for Green Summer (c1864) demonstrate his experimentation with groupings of figures, along with his use of red chalk to create a gentle dream-like atmosphere. The PRB often drew on history and literature and there are several good examples here such as Rossetti’s Sir Lancelot’s Vision of the Sanc Grael: Study for the Fresco Painting in the Oxford Union (1857) and The Death of Lady Macbeth (c1875-6).

[image5]

The final room of this exhibition is focused on landscapes and the pre-Raphaelite’s departure from academic training to work out of doors. Their intention was to handle light and shadow in such a way that they would be able to capture every tiny detail in front of them. The intensity of the colour in many of these works is because of the use of gouache, rather than transparent washes. In an array of geographies and subjects, some painters remained in England, finding beauty in the everyday scenes around them while others travelled the world. From the familiar landscape of southern England to the ancient ruins of Jerusalem or Pisa, these artists conveyed nature in the most acute fashion.

[image7]

Thomas Seddon’s Jerusalem and the Valley of Jehoshaphat (1854) conveys the arid landscape perfectly, while William Henry Millais’s A View in Yorkshire (1850s) is a verdant scene capable of sustaining livestock. One of the most astonishing paintings in this part of the exhibition is Albert Moore’s Study of an Ash Trunk (1857). Moore was 16 years old when he painted this close study of the tree and surrounding foliage – hart’s tongue fern fills the picture to the left of the trunk, which is covered in ivy. Interestingly, Ruskin’s The Elements of Drawing advises artists to draw ivy around the base of trees. In Ruskin’s own studies from nature, such as Spray of Olive (c1870), he is careful with angle and detail, aiming to capture unique individual form.

[image6]

I left this exhibition with a renewed interest in, and respect for, the work of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. I am not sure I will ever appreciate paintings such as William Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World (1851-53), but the drawings and watercolours in this exhibition have made me think again about the artists of the PRB, about their ideas and techniques and, above all, the tenderness with which they approached their subjects.