Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

6 October 2018 – 20 January 2019

by CHRISTIANA SPENS

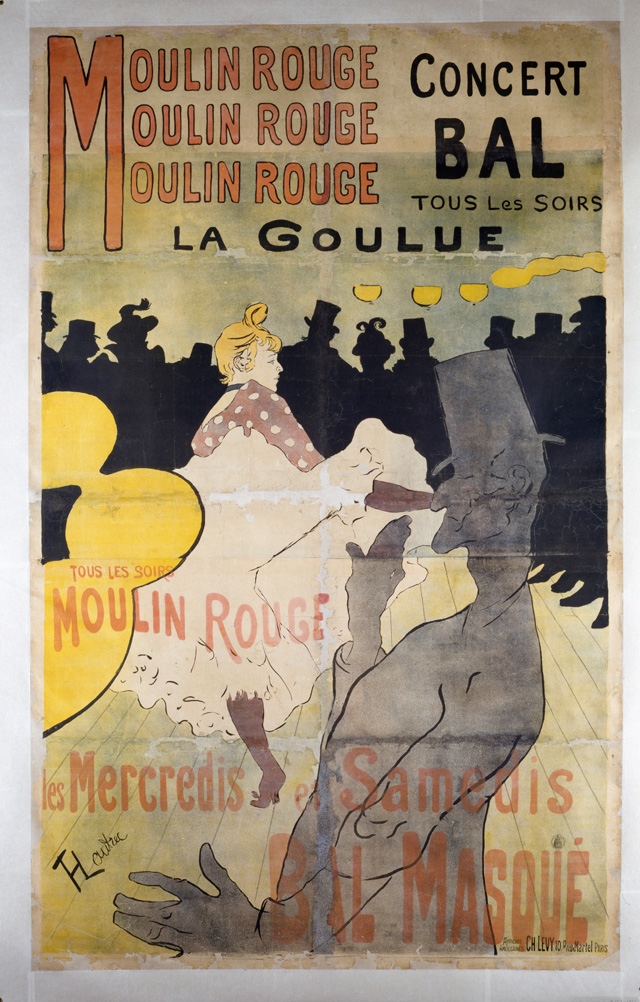

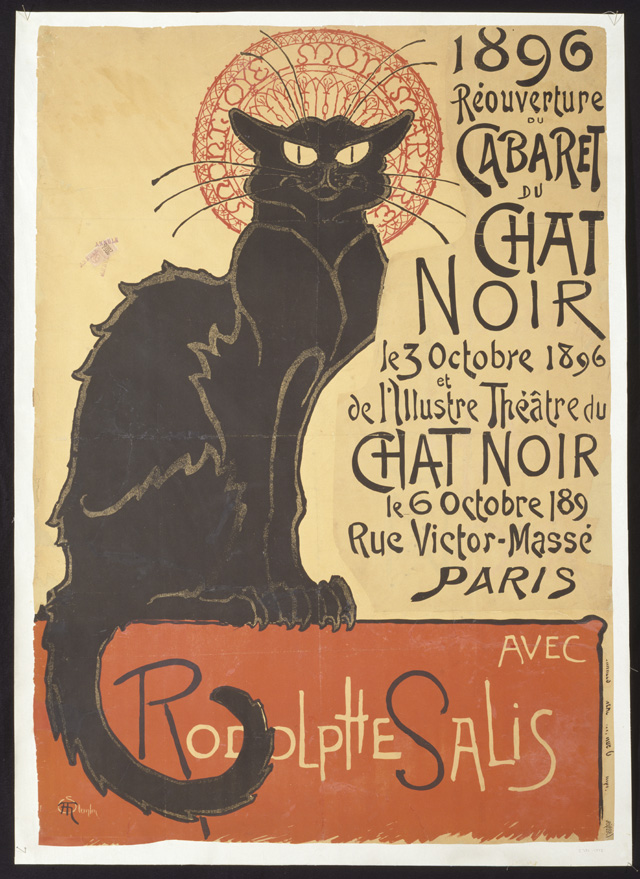

Montmartre, Paris – these words alone are enough to conjure the famous images of Le Moulin Rouge, Le Chat Noir, the nightclubs and dancers of the fin de siècle that have become so deeply associated with the city of Paris and, indeed, any idea of “Frenchness”. Girls dancing in a flurry of movement and costume, singers brooding dramatically against a darkened backdrop, and couples laughing coquettishly over champagne all construct a lifestyle and a place, a subversion to aspire to, that has never really faded.

[image5]

Much of this sparkling mythology around the “city of pleasure”, as it was once known, is due to a handful of images, the works of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) and his peers, who were among the first to use images to publicise events, entertainers and a fashionable subculture. Using the technique of lithography and the recent invention of the poster, they produced large-scale invitations to a bohemian, underground world, creating a mythology that would continue for decades, and sparking the development of advertising as we know it. It is strange to imagine that there was a time before billboards and visual publicity – that promotion was once entirely by word of mouth – but what we now take for granted was developed to attract audiences to the dance halls of Paris, tantalising potential punters with vast posters of flamboyant performers.

[image3]

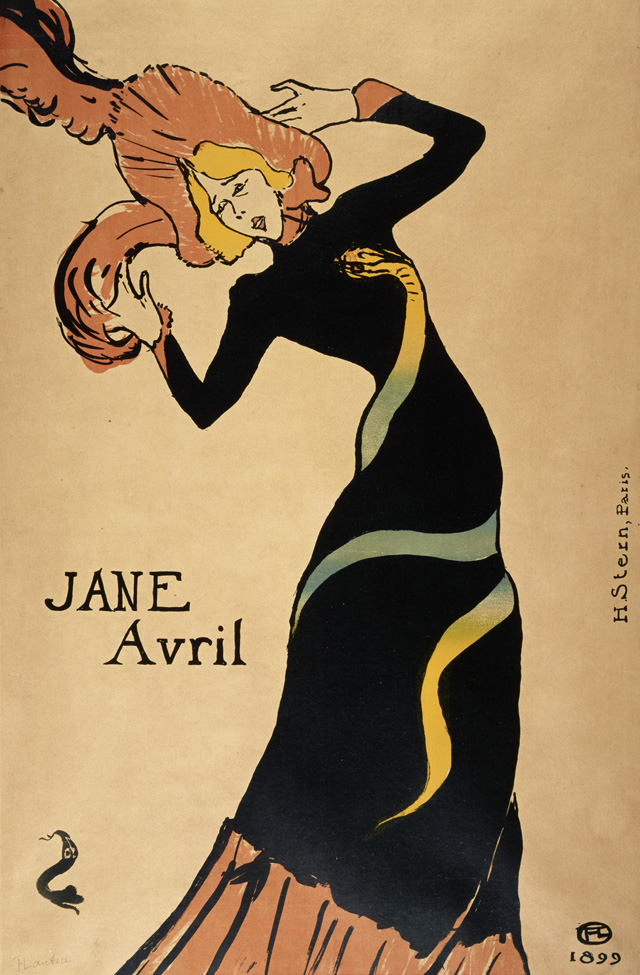

While Pin-Ups focuses on the notion of “celebrity”’, the exhibition is as much about the celebrity of a city, or rather, a neighbourhood, as it is about any dancer or singer in particular. The various stars (including Yvette Guilbert, Jane Avril and Aristide Bruant) who adorn the posters are all part of the same vision of a performance, which was ongoing and multifaceted. Walking around the exhibition, in fact, I begin to think of the posters as documentation of a larger artwork – the scene in fin-de-siècle Montmartre itself (and perhaps, even, the idea of “a scene” at all). These images, while clearly brilliantly accomplished in their own right, are also records of a more ambitious invention – the transformation of a neighbourhood into a subculture, a way of life and an endlessly running performance: the turning of life into art, where the images are but signposts to the grander spectacle.

While the posters of Toulouse-Lautrec, Pierre Bonnard, Théophile Alexandre Steinlen and Jules Chéret are entertaining and beautiful, and shed light on a fascinating era in Paris, walking around the exhibition is like being given lots of invitations to parties and performances that no longer exist. It is tantalising and enjoyable, but there is always a sense, perhaps inevitably, that the most interesting scenes, figures and stories are out of frame. The problem with exhibiting advertisements is that the story only begins; there is no development, no drama, no catharsis, but simply a series of “what ifs?”, suggestions, brief illusions: a glimpse of a vision, but not the full manifestation of it.

[image4]

Perhaps for that reason, my favourite part of the show is the footage of the dancer Loie Fuller performing in 1896, captured by the Lumière brothers. Here, she creates, with a costume that resembles wings or petals, the excited motion of a flower budding and collapsing, over and over again. It is mesmerising and beautiful, and gives the rest of the show an important sense of context. Toulouse-Lautrec and his peers were artists in their own right, but these particular images were communicating the joy they felt in witnessing these other, more ephemeral artworks, and indeed the birth of a subculture that inspired them. They are like love letters referring to a romance we will never know. Despite some sense of nostalgia for a world we never experienced, there is something moving in bearing witness to the inspiration and longing that the people of this time inspired in one another.

[image2]

This notion of nostalgia, though, as we cannot forget (these are not really love letters, after all, but billboard posters), was also very lucrative. There is something funny about an art scene that was always so self-consciously bohemian and rebellious being, from the beginning, so concerned with its commercial appeal. But then, in Montmartre, where art was grounded, inspired and bankrolled by prostitution and drinking, that is fitting. These artworks are about pleasure and escapism; they helped to construct a place that promised to take people out of their everyday lives and difficulties and give them something magical and glamorous. Pin-Ups does this, too. While the performances and entertainers it features have long gone, there is something inspiring and infectious about the construction of a world rooted in fantasy and illusion. Does it matter that these things are ephemeral, its people fleeting? If Toulouse-Lautrec and his peers reveal anything, it is that fantasies sustain indefinitely.