Art Space Gallery, London

10 September – 8 October 2021

by EMILY SPICER

On a quiet road in Islington, north London, away from the hubbub of the high street, Art Space Gallery has opened its doors for the first time since the pandemic began with an exhibition celebrating 40 years of aquatints by Royal Academician Peter Freeth. Aquatinting is a technique that allows for graduated tones in etchings, produced by adding texture to the printing plate. Freeth’s painterly manipulation of this process has been developed through the decades, but his prints have a timeless quality. Drawing on themes such as mortality and decay, he manages to produce images that are soft and fluid, while also looking as though they have been chiselled into granite, rather than printed on paper.

[image5]

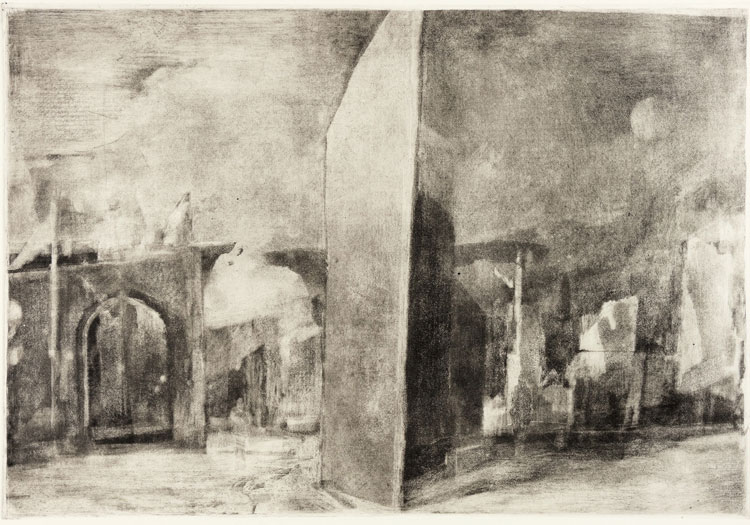

In Freeth’s etching Divided City with Broken Aqueduct, a tall, smooth obelisk bisects a ruined cityscape. It looks out of place, like an otherworldly presence, reminiscent perhaps of the strange black monolith in the opening scene of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. A globe hangs in the grey sky. It is not the moon, for the moon never appears as shaded in the round. It seems, instead, to be a planetary sphere, risen above the remains this odd classical city. On the left, a street leads to a fractured aqueduct and a ghostly figure walks towards us. On the right, in front of ruined pillars and walls, a second, indistinct, figure stands in the shadows. What are we to make of this uncanny scene? Is this Berlin, divided by its cold war wall? Is this Rome, shattered and sacked? Or is this another planet entirely, a ruined world existing in parallel to ours?

[image6]

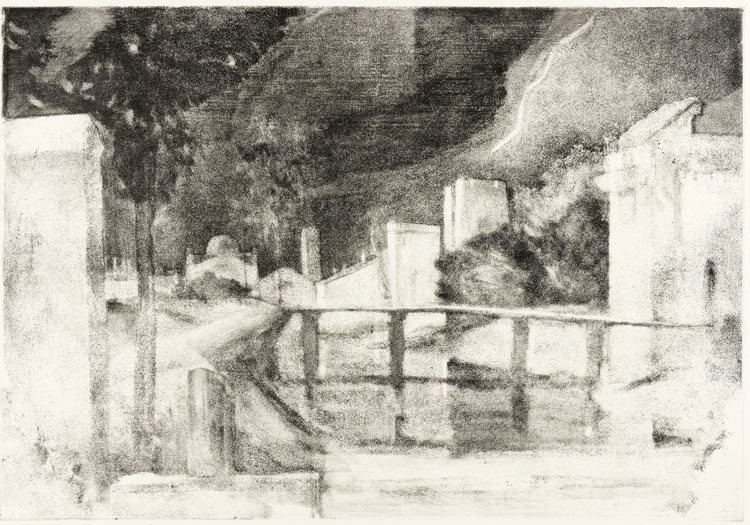

Ambiguity draws us into Freeth’s work, but art history helps us decipher it. A Glimpse of the Tempest is lifted directly from Giorgione’s The Tempest (1508). Freeth has extracted the landscape from the Italian master’s painting, zooming in on the bridge and buildings in the background, omitting the figures in the foreground. In both works, lightning forks the sky, and two broken columns poke up out of a wall. Do these two columns represent lives cut short? Is some catastrophe about to sweep through the landscape? There is no definitive reading of Giorgione’s image, but by choosing to focus on the township in the background, Freeth is perhaps making this portentous section of the scene refer to civilisation at large.

[image2]

This exhibition was originally scheduled to open in May 2020. Instead, it opened on 10 September, the day before the 20th anniversary of 9/11. With this in mind, Freeth’s modern cityscapes, his grainy impressions of skyscrapers, have an extra resonance. The granular appearance of these towers and the dark clouds of ink that seem to engulf them, conjure a sense of desolation, of an end of things, echoing the images that filled the newspapers two decades ago.

[image4]

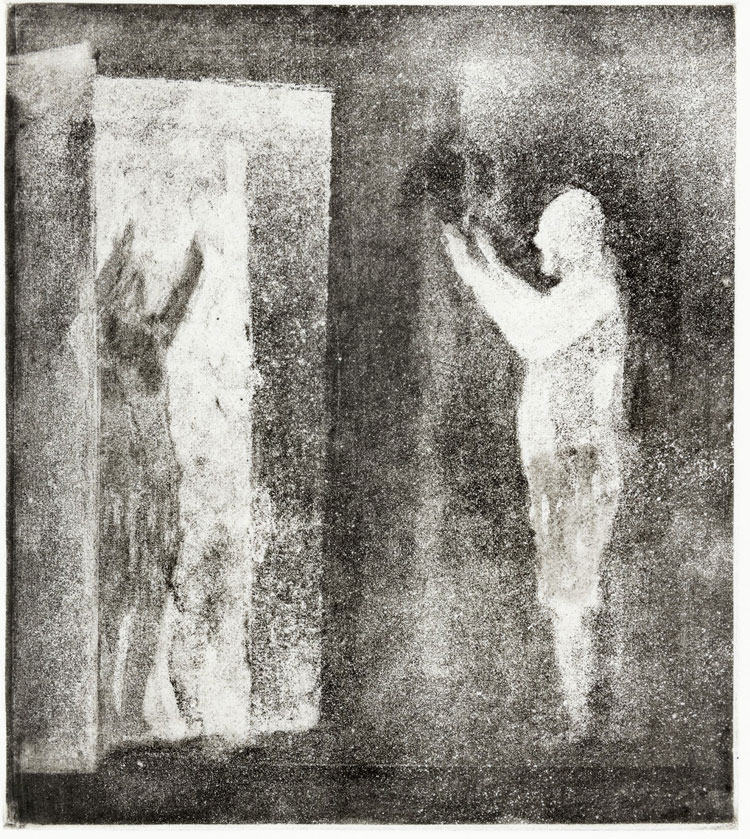

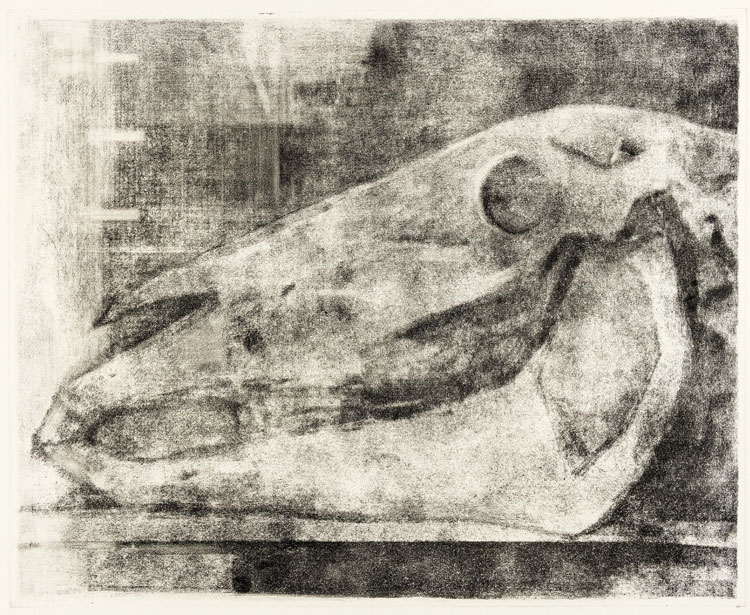

All Freeth’s etchings have a quiet monumentality about them, a sense of the inevitability of things. Horse skulls act as memento mori and sunken faces resemble death masks. That most portentous of creatures, the crow (or perhaps it is a jackdaw) is a recurrent image, as though the bird keeps appearing on the windowsill of Freeth’s studio. One work, titled Mr Parkinson Practices His Surrender, alludes to the disease the artist has had for almost a decade. The image illustrates a man with his arms raised, while his dark mirror image copies the gesture without getting it exactly the same. It is as though he is facing the disease directly in his own likeness, and it has a mind of its own.

[image3]

The human condition, our vulnerabilities and our frailties, is a key theme in Freeth’s work. Two small prints depicting Adam and Eve as a middle-aged couple, points to the everyman aspect of their story. Here, they have aged, but have not learned their lesson. Eve is seen from behind, reaching up as though picking another apple from the tree. Other images have a note of irony about them. The etchings named The Good Samaritan depict a strangely gowned figure looking down at a body sprawled on the ground. In one of these, the person we assume to be the Samaritan stands with his hands on his hips in a gesture more akin to disapproval than compassion.

[image7]

The sombre mood of Freeth’s work lies not just in his subject matter. His carefully honed approach to aquatinting produces a grainy image that sometimes resembles a photograph from a newspaper that has been photocopied repeatedly until the details have become lost. This is not a criticism; the quality produced is an evocative one. It is as though we are looking into the distant past and the future all at once. What is happening now has happened before and will happen again.

It is through art that we remember and are remembered. In the last room of this exhibition, a print of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 65, looks very much as though it has been etched on to the wall of a mausoleum. It begins: “Since brass, nor stone, nor earth, nor boundless sea/ But sad mortality o’er-sways their power/ How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea/ Whose action is no stronger than a flower?’ It ends with the line: ‘That in black ink my love may still shine bright.” It is tempting see this choice of sonnet as a touching nod to Freeth’s own mortality, and the hope that he will live on through his art.

[video1]