by ANGERIA RIGAMONTI di CUTÒ

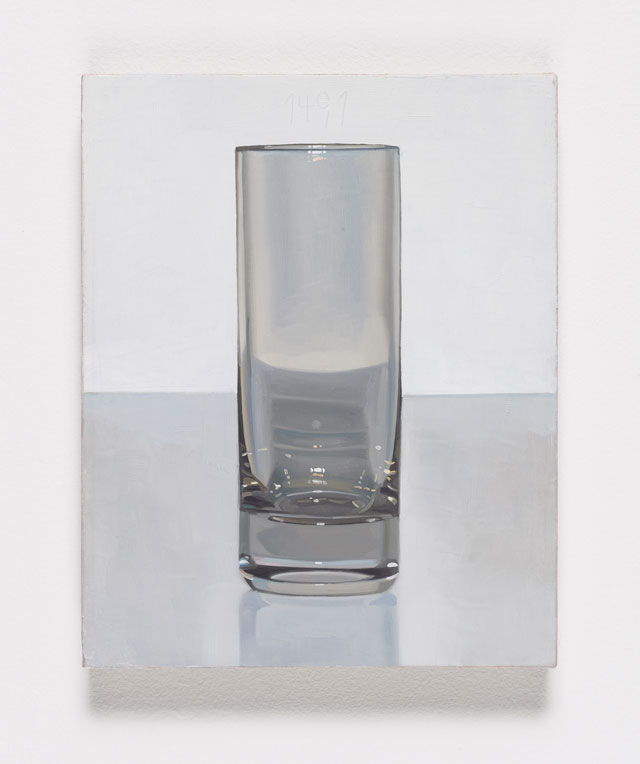

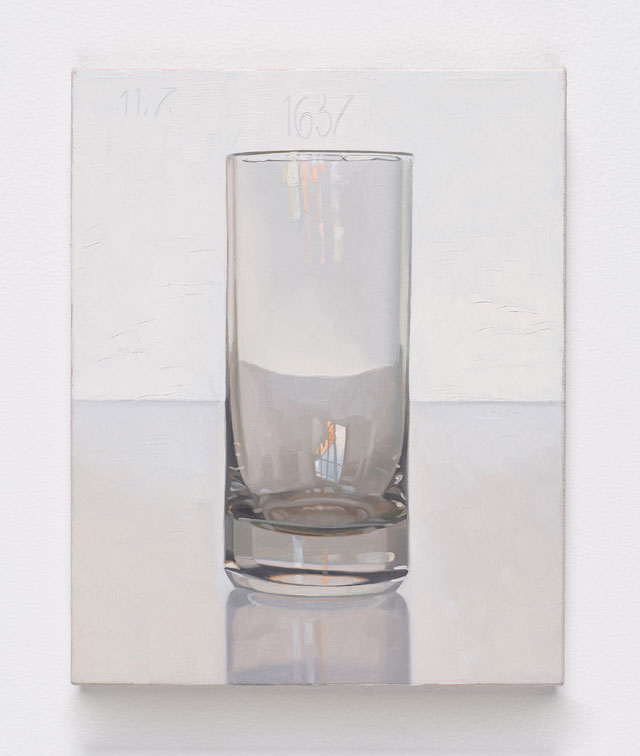

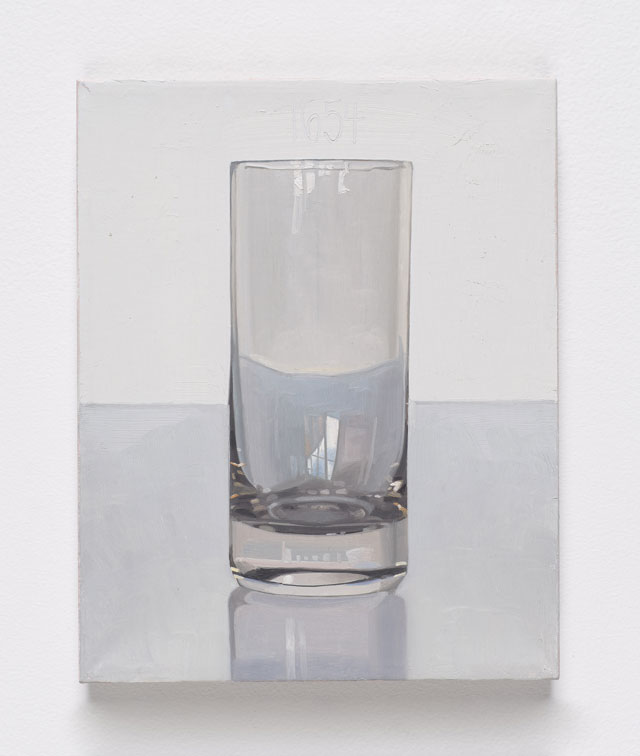

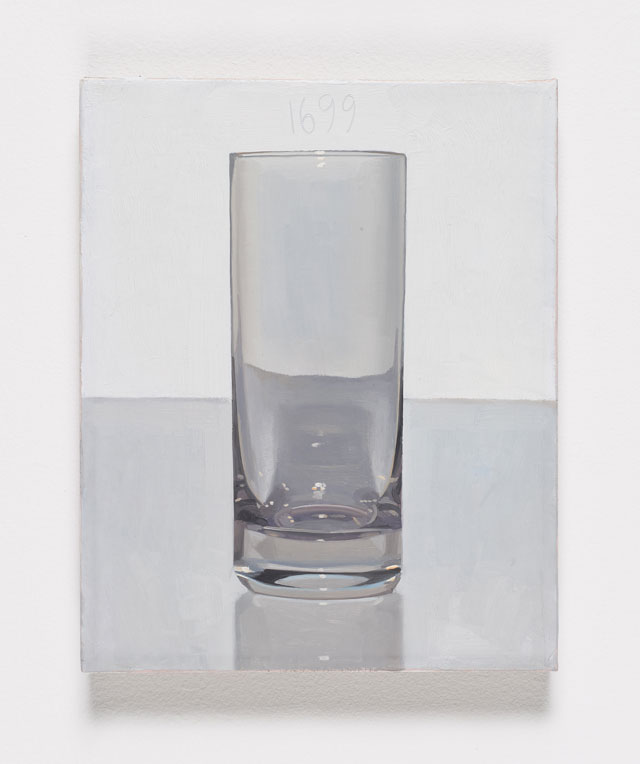

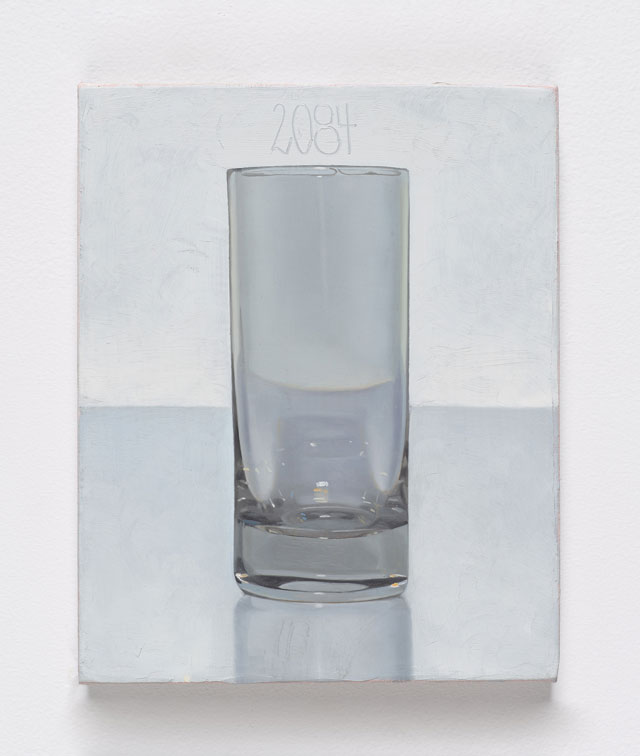

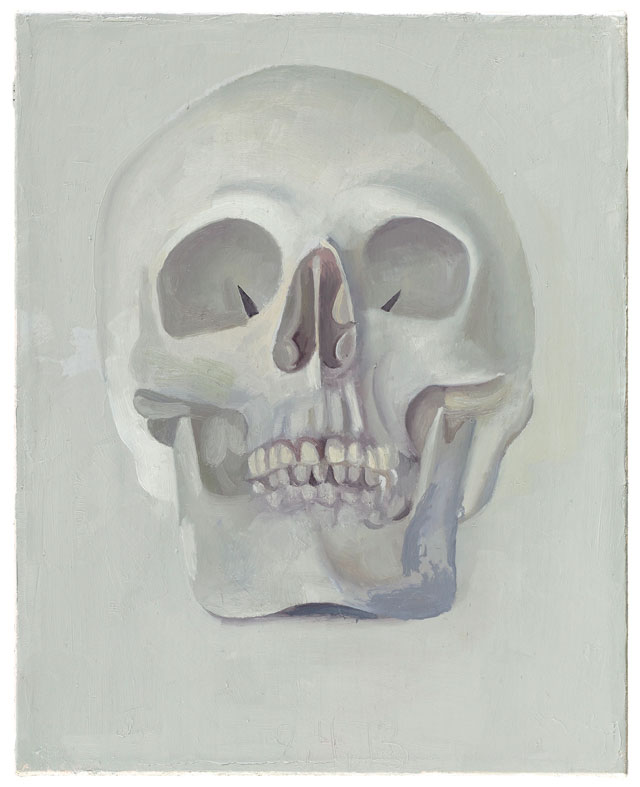

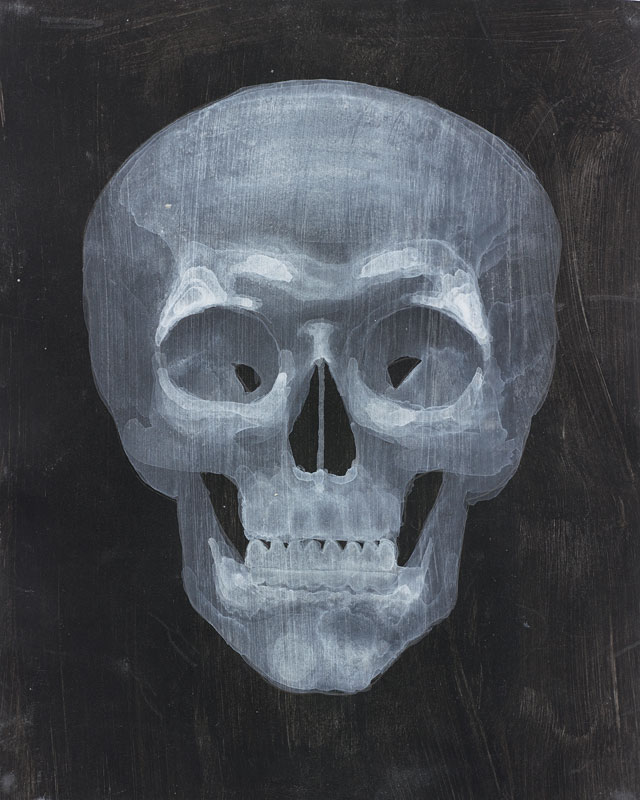

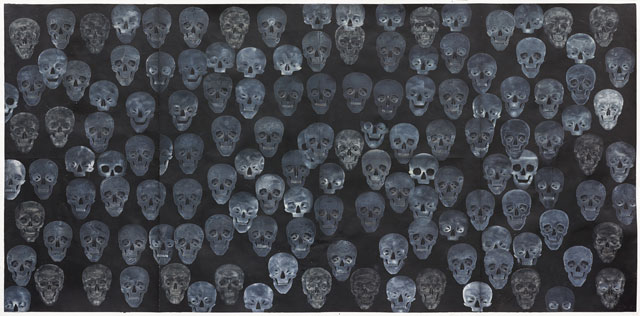

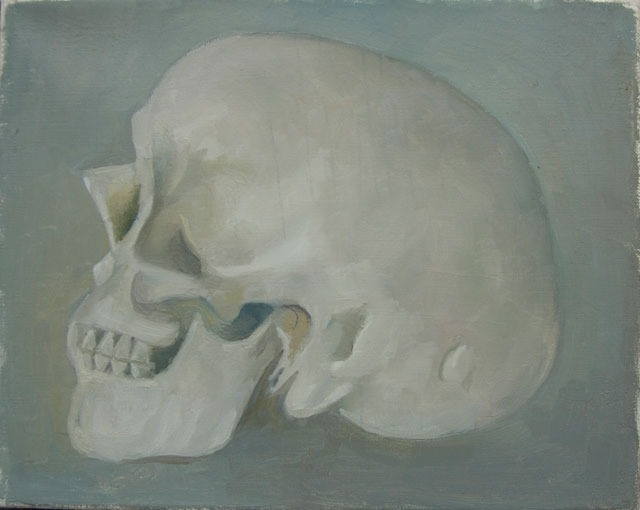

Peter Dreher’s epic series Day by Day, Good Day consists of infinitesimally varying versions of a cider glass, a painted record of thousands of days and nights of the past 42 years or so. Detached from the tumult of the 60s, Dreher (b1932, Mannheim, Germany) has steadfastly, perhaps defiantly, stood his ground in the realm of broadly realistic painting, with occasional forays towards abstraction. How he approaches the tenuous concept of realism is partly explained by his interest in Husserl’s phenomenology, prompting a visual study of the workings of perception itself rather than the documentary representation of an object that can never be fully apprehended. Within his pursuit of art for art’s sake, in which the concept of repetition is used as a philosophical concept as well as a means of liberation, Dreher’s other works include compelling series of skulls and less gestural, glassy interiors.

Angeria Rigamonti di Cutò: Can you describe something of your childhood living under the Nazi regime: what was it like and did that traumatic context influence your becoming an artist?

Peter Dreher: I wanted to be a painter even before I could think. So that decision was not shaped as a result of my experiences in the Napola (Nazi National Political Institutes of Education).

I did, however, suffer from traumatic events in that period. I was struck by the images of the apartments in Mannheim, out of which furniture, clothes and washing were thrown. I saw SA men in brown uniforms [the paramilitary wing of the Nazi party, commonly referred to as Brownshirts] running frantically out of the buildings.

Books were thrown into a heap and burned. This is how I witnessed the Reichskristallnacht [Night of Broken Glass] in 1938. People were standing there looking on in silence.

The two years I spent in the Napola was one of the worst experiences of my life. It felt like being in a barracks and under constant observation. I was never left alone there.

ARC: In terms of institutional education, it’s always interesting to see who an artist’s teachers and students have been. In your case, you were taught by exponents of German expressionism and Neue Sachlichkeit [new objectivity]: Erich Heckel, Karl Hubbuch and Wilhelm Schnarrenberger. Formally, there’s little apparent trace of those influences in your work as you seem to have a more neutral gaze, but are there, in fact, ways in which you were affected by those teachers?

PD: I experienced Erich Heckel as a distinguished and educated man, who critically questioned his times. He created in me an awareness of the challenges presented by painting and encouraged my own efforts in this direction, allowing me to give full rein to my talent and potential. Even after he retired, he remained a fatherly friend to me and I would often visit him at his home at Lake Constance. After one discussion on painting, he gave me an overwhelming gift – presenting me with his oil paints and brushes.

I experienced my first tutor at the Academy, Karl Hubbuch, as a strict and assertive type of teacher. Once, when I showed him my drawings during a discussion, my fellow students and I feared a harsh reaction because they were sketched in the then unusual new objectivity style. We waited anxiously for his reaction, which took some time coming while he rolled his cigar back and forth in his mouth. But the harsh criticism was not forthcoming; instead, Hubbuch expressed himself favourably and critically on my works.

ARC: As a professor yourself at the Academy of Visual Arts in Karlsruhe, one of your students was Anselm Kiefer whom you supported in his controversial Heroic Symbols series. What was your experience as a teacher, particularly in that period around 1968 when the student-pupil relationship was theoretically at its most volatile?

PD: I did not get involved in the smouldering discourse, which towered over everything, but tried to maintain a neutral stance. I encouraged my students – still wet from the effects of water cannons on returning to their workplace after demonstrations – to continue their artistic work. From today’s perspective, the academy in that politically heated period was an oasis of neutrality where you concentrated on your art, unimpressed by political discourses.

ARC: Apropos of that historic era, you recognised Zen Buddhism as an antidote to the 1960s, which you described as characterised by “the hectic hustle and bustle, superficiality which is how I perceived the 60s”. It’s unusual to encounter someone who lived through that decade to speak of it in apparently negative terms?

PD: Although I observed this period with all its confrontations, I did not find that it had any formative effect on me. For me, the 60s were shaped first and foremost by grappling with the artistic movements of this period – particularly from the US.

ARC: With the self-imposed restriction in your ongoing lifework Day by Day, Good Day, you’ve made repetition your raison d’être, going against the grain of artists seeking to “reinvent” themselves. Did you see the possibility of tackling all the problems of art history through the continued representation of that one object?

PD: Yes, I think so. The confinement to a single motif opens up the opportunity for me to concentrate fully on the painting process and its infinite possibilities. For me, adherence to the same subject is not a limitation or restriction, but rather a liberation from the compulsion to reinvent myself and the painting process time and again, seeking the breakthrough motif.

ARC: The repetitive aspect of the series could be viewed as mesmerising or confining. You’ve referred to an interest in Zen Buddhism that gave the work its title, so the mantra-like aspect of repetition comes to mind, but the series was also recently exhibited at Reading Prison in a collective exhibition, the implication being that the work was comparable to the experience of enduring time in prison. Is there any sense in which you have experienced this work as an endurance test?

PD: Again, adherence to one motif and its repetition does not represent a limitation but rather a liberation. It allows me to concentrate on what is really important to me – the painting process itself. For this reason, I would describe myself as a happy Sisyphus. Rolling a boulder up a hill over and over again is neither destiny nor punishment but rather a self-made decision that I feel very comfortable with, because I succeed in seeing my subject (the glass) afresh each time – as if I were seeing it for the first time. What is important to me is not inventing a picture but experiencing the infinite possibilities available in the creation of the image.

ARC: You’ve said: “Painting is the purpose itself. Our visible reality is the cause for painting, or the catalyst, with the subject being of minor importance.” In view of this, it’s perhaps surprising that you did not go further still and eliminate the subject altogether, moving into fully fledged abstraction?

PD: I had an abstract creative period from the 70s to the 80s. During that period, I was definitely influenced by the highly regarded and omnipresent abstract painting of the 60s to the 80s. In my works from this period, I strove for a neutral stance vis-a-vis the motif – as was the case later with the Day by Day, Good Day series. Ultimately, however, I realised that I needed the reality that surrounded me in order to become inspired to paint.

ARC: You chose painting, and realistic painting at that, in a period when conceptual art was all the rage, and you have refuted a conceptual reading of the Day by Day series. You have, however, said that American artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg, whose work you encountered at the 1964 Venice Biennale, affected you. Given that they were the dominant figures of the time, it must have taken considerable resoluteness to have persevered with realistic painting in that climate?

PD: As early as my student days, realistic painting was regarded with a certain mistrust and disdain. This may well have been due to the fact that in the Third Reich, art also suffered from having been forced into line. As a result, anybody who wanted to survive under the regime painted realistically. By virtue of this experience, realism was not highly considered in the postwar period. Fortunately, I am scarcely susceptible to current fashions and styles and in this regard they have little influence on me. I thus prevailed with my style – even in an abstract environment, first as a student and later towards my contemporaries and colleagues.

ARC: In other series, you have cast your gaze on two other elements favoured in the 17th-century northern still-life tradition: flowers and especially skulls – in a myriad of variations – and in some cases depicted almost as if they are x-rays. Did you view these differently from glass? Were you focusing here more on the vanitas aspect associated with these objects?

PD: Skulls and flowers impress me just as much or just as little as the glass. They are nothing other than motifs to be painted. What fascinated me about the model of the skull is its perfect and spherical form. With the glass, it was the transparent and ephemeral aspects, to paint something that is actually transparent and thus not visible. With flowers, it was the ornamental frame of reality that attracted me.

ARC: You have also produced some compelling work in quite a different style within the wide spectrum of realism, less gestural, more of a glossy photorealism, often fragmented into a grid–like format; I’m thinking here of works such as the Freiburg interiors and garden, Beachcomber Shores and New York street views. They are so intensely different to the glass series: what interests were you investigating in these works?

PD: For me, each fragment is the detailed view on reality, just as the single image does not consist of a large overall form, but of individual islands of paint joined together. I am extremely interested in Edmund Husserl’s concept of phenomenology. He describes perception as something that can be described rather than as the complement of what is absent. Objects are never presented to us in their entirety. We never have the complete view of them. In actual fact, an object is altogether imperceptible. By the individual images that afterwards result in the complete picture, I illustrate that seeing is always accomplished as a concentration focused on to one point – the rest being “shaded”, blanked out. In my pictures I underline the act of seeing.

• Peter Dreher: Day by Day, Good Day is at the Mayor Gallery, London, until 2 June 2017.