Michael Werner Gallery, London

24 February – 21 May 2022

by BETH WILLIAMSON

It has been almost 13 years since the last major UK exhibition of work by the Danish artist Per Kirkeby (1938-2018) was shown, at Tate Modern in the summer of 2009. Now, Michael Werner Gallery brings a small selection of Kirkeby’s paintings from 1965 to 2015 to London. With what feels like the early arrival of spring this year, it is a good time to open such a vibrant exhibition of painting in the capital.

Kirkeby did not have a conventional beginning to his artistic career, if there is such a thing. He joined the Experimental Art School in Copenhagen in 1962 after abandoning his academic studies in natural history. An alternative to the staid Royal Academy, the Experimental Art School led Kirkeby to encounter some of the most radical art, music and poetry around. He joined just a year after the school opened its doors and encountered the music of John Cage, the painting of Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze), the poetry of Henri Michaux, and the work of Joseph Beuys, who would soon become Kirkeby’s friend and mentor. Still, as we shall see, his interest in and understanding of geology never left him. Indeed, by 1962 he had already participated in two expeditions to Greenland. In a rather different sort of trip in 1966, Beuys and Kirkeby made an imaginary journey with their wives to Manresa village, a place of pilgrimage and spiritual enlightenment, in the Pyrenees. Beuys performed the action Manresa later that same year and Kirkeby wrote about their journey.

[image4]

Around this time, he began to make his paintings on Masonite, a kind of hardboard. As Achim Borchardt-Hume pointed out on the occasion of the Tate exhibition, these Masonite paintings of the 1960s combined references to contemporary visual culture with others to historic artists such as Gustave Moreau and Giovanni Segantini. The early examples in this exhibition at Michael Werner Gallery do just that with two untitled works from 1965 and 1968 alongside the wonderfully atmospheric Dunkle Höhle [Dark Cave] (The Dream about Uxmal and the Unknown Grottos of the Yucatan) of 1967. These surely lend material proof, if it were needed, of Kirkeby’s belief in the inextricable relationship between nature and culture. This was underlined by his enduring interest in Henry David Thoreau’s American classic Walden or, Life in the Woods (1854), a book for which he later provided an illustration.

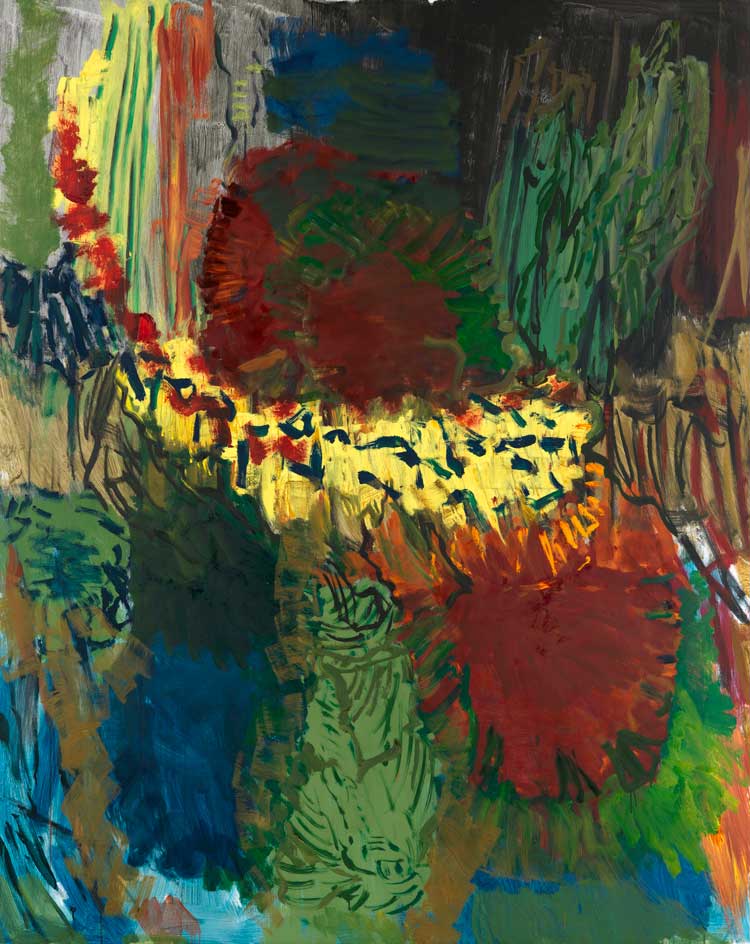

In the late 1970s and early 80s, Kirkeby moved away from Masonite to oil on canvas and a freer more gestural practice than he had previously explored. We see just two dark examples of these in this exhibition, both from 1981. The works in the rear gallery, by contrast, are luscious beyond imagination and there is a real sense of being surrounded by verdant foliage, lost in the middle of a rich natural world that sustains us. The landscape is a constant reference. Five of the six paintings here are from the 2010s, with one from 1995. Their liveliness is a joy and such a noticeable shift in tone from the seriousness of the first gallery space. Most works here are untitled, but Mayalandet 2 (2011) seems to reference his visit to South America and Mayan ruins decades after the trip and the making of Dunkle Höhle (1967). Untitled (1995) positively shimmers in yellow and gold. This is just one example of a body of work from the mid-90s that Borchardt-Hume describes as having “chromatic exuberance”, and I really can’t improve on that.1

[image3]

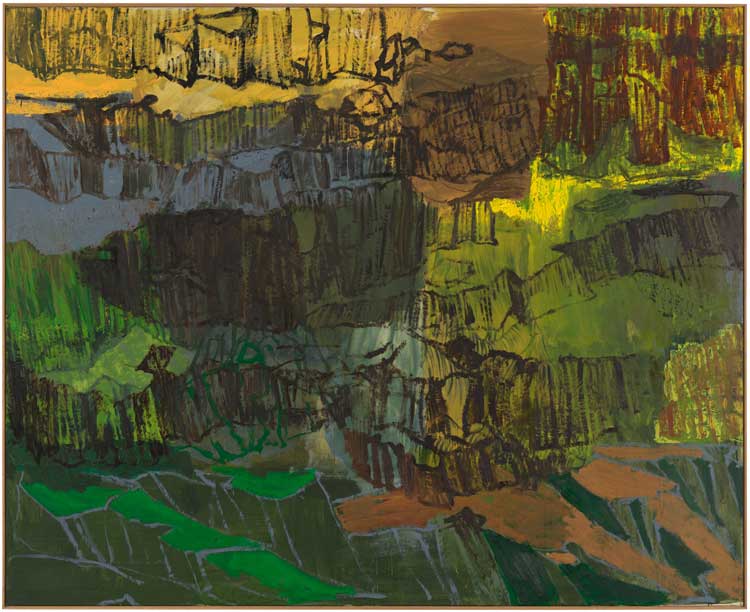

Things take a darker turn in the small downstairs viewing room. In works such as Inferno IV (1992), Plateaus I (1999), Untitled (2005) and Teodora (2011), it is as if Kirkeby takes us underground, beneath the surface of the earth to explore the unseen strata beneath, while still retaining a grip on the surface and its vegetation. There is an intimacy about these works that engages us on a sensory and psychological level simultaneously. The picture space in Inferno IV, for instance, somehow manages to be unsettlingly oppressive (presenting its scratched, scribbled and painted surface as a material challenge) and at the same time offer space for psychological experience, through openings, or portals, of a geological underworld that Kirkeby understood and opened up to his viewers.

The final gallery in this exhibition contains his most recent works, many from 2015, just three years before his death. The hanging of six late Masonite boards together here is stunning. I said earlier that he moved away from Masonite to canvas, but he never left it behind entirely. In these late examples, he often uses blackboard paint as a ground of sorts, lending them a playful, childlike quality, despite their darkness. This is especially so where he uses chalk and small paper collaged items. These six works are more drawings than paintings. Kirkeby’s own words on drawing are helpful in understanding them as, perhaps, material remnants of thinking. “Drawings are full of untrammelled thought and devoid of language … I have never drawn in order to produce something. But simply in order to find something out.”2 In a broader sense, all Kirkeby’s work in this exhibition might be considered in the same way, the material remnants of thinking through a lifetime of nature and culture entangled. If you want to untangle that further, visit the exhibition.

References

1. Per Kirkeby by Achim Borchardt-Hume, published by Tate Publishing, 2009, page 25.

2. Tafeln, Zeichnungen, Monotypien by Per Kirkeby (trans. Jeremy Gaines), published by Michael Werner, 2000, unpaginated.