by ANNA McNAY

Penny Slinger (b1947, London) was a lively and prominent figure on the 70s London arts scene. She studied at Chelsea School of Art, where she wrote her thesis on Max Ernst, and, after graduating in 1969, was offered a place at the Royal College of Art. That summer, however, she met and fell in love with a young film-maker called Peter Whitehead. They decided to go off and make work together, including the 1969 film Lilford Hall, currently on show at the Hayward Gallery (History is Now, 10 February – 26 April 2015). After the breakdown of their relationship and a dark period of self-examination, questioning both who she was and where she fitted in to the contemporary art world, Slinger discovered tantric art. Seeking a spiritual guide, she met Nik Douglas, and, with him, moved first to New York and then, in 1979, to the Caribbean.

She returned to the US in 1994, but Slinger’s legacy in the UK was all but lost until 2009, when she reappeared in an exhibition, Angels of Anarchy, at the Manchester Art Gallery. Since then, she has had several exhibitions around the country and is firmly re-establishing her place in British art history.

Anna McNay conducted a Skype interview with Slinger, at her home in Boulder Creek, California to talk about the missing years of her career and where she sees herself now.

Anna McNay: You were a prominent figure on the London arts scene in the 70s, but then, in 1979, you retired from the art world for a few decades to devote yourself to spirituality. What made you decide to do this?

Penny Slinger: Well, it wasn’t so much a retirement as a shifting of gears. I don’t think I’ll ever retire from art. Art has been my passion since I don’t know when. I could draw almost before I could walk. So I’ve always known that I was an artist in my heart and soul.

When I walked into the Hayward Gallery’s Tantra exhibition in 1971 – the first major exhibition in the UK of tantric art – it was as if I’d come home. I just stood there, spellbound, saying: “Well, this is it! This is the next stage, this is the next evolution.” I spent the next years really trying to find out more about tantra. I went to lots of lectures, but mainly it was book knowledge. Then I got together with Nik Douglas, who, at the time, was one of the main westerners who really knew about tantra.

The surrealists had delved into the subconscious, but this was at the level of the superconscious, an expanded level of consciousness. There was a simple bliss to it. It was like an essence, a distillation of everything. For me, tantra is the supreme spiritual path that encompasses everything: science, art, philosophy, physics, sexuality. Everything is in there, in this magical weave. I see it as being the way to explore one’s multidimensional nature. It’s got so undefined now, though, because of the neotantric movement. Now tantra is known as the religion of sex, but that’s a diminution of it. In fact, tantra means to weave, but also to expand – weaving all the parts of one’s life together in this fabric and also being able to expand into your full, richer self.

So, finding tantra and meeting with Nik, I embarked on a new phase of my art, which I felt would be meaningful. I’d been dredging the depths of my own psyche and now I saw a way to expand that. We started working on a book, Sexual Secrets: The Alchemy of Ecstasy, for which I did more than 600 drawings. It was that book project that took us from England to the US. We thought, first of all, it would be a quick, couple of months, project, but it turned into more than a two-year endeavour. The editor wanted to work closely with us, so we moved to America, to the New York area.

When that was complete, we had to decide whether to stay in the US or not, and I really followed Nik, who had been brought up in Cyprus and wanted to live in the islands. We moved to the Caribbean, where I lived for 15 years and, I would say, had a whole mini-art career. I became really interested in the pre-Columbian culture of the island because it was very rich in archaeological finds. I immersed myself in that and paid tribute to the indigenous people, the Arawak Indians, for the period that I was there. Then I re-emerged and came back to America, to California, in 94. I moved here and have been here ever since.

AMc: You also had a gallery in the Caribbean, I believe?

PS: Yes, that’s right. First of all I exhibited in one of the local galleries. They showed my Arawak art pieces and they were very well received. Then we decided to open a gallery ourselves, the New World Gallery [in Anguilla]. It was interesting because I was making art for a different public and therefore had a whole different set of rules and criteria.

I’d had a big exhibition in 1982 at the Visionary Gallery in New York and I’d been very excited – it was a mini retrospective – and this, for me, was like a litmus paper to test the waters because I’d already moved to the Caribbean and I came back for this exhibition. My feeling was that if this was well accepted, then I could continue the work that I’d been doing, which was pretty cutting edge and dealing very much with sexual identity, but I was so disappointed because, well, to put it in a nutshell, men really loved the work and wanted to buy a lot of it, but, in the end, none of them ended up buying any because they thought that I went with the work – and I was not available in that way! Then I understood that we weren’t dealing with a very mature culture here and that really the climate wasn’t fertile to receive what I was trying to offer. So I said: “OK, time for a change.”

Being in the Caribbean, I couldn’t show the work I was making because it would be too challenging to the local culture – they were African-based people mainly, but had been steeped in a Christian culture and what I was doing would just not be understood and would be way too threatening. I decided instead to try and use my art as a bridge to communicate and to give something back to the culture that I was now living in. So I embarked on this series bringing the Arawak Indians back to life. There were no pure-blood Arawaks left in the region, but their spirit was very much in the land and in the artefacts we were finding. I wanted to depict the people behind those artefacts. I dedicated close to 15 years of my life to that work. Luckily, a lot of local people bought the art. They didn’t buy it because they were art connoisseurs, they bought it because it spoke to them so strongly that they couldn’t stop thinking about the pieces and had to get them. That’s the best way to buy art – not as some kind of investment or some kind of cultural phenomenon, but because it speaks to you strongly. So now a lot of these Arawak Indians are hanging on the walls of people living in Anguilla, the island where I was living. These Indians had been forgotten by the islanders until I put them in the murals at the airport and in the art that I created. I was pleased with that result. It was like an art-career insert.

Then I came back and made a film, Visions of the Arawaks, in New York at a video studio there, which brought the whole series together with my poetry and completed that cycle in my offering.

AMc: Have these works been shown elsewhere, outside the Caribbean?

PS: Only really in the film, not as a body of work. About half of them got sold and the other half I have here. I’m waiting for a venue to be able to share them here – with the film as well. The film has had some showings, but it hasn’t reached out as much as I would hope. The indigenous people really knew how to live with the planet and with nature, and modern civilisation has forgotten that knowledge. So I feel that the indigenous way holds the key to our survival in the future. That’s why sharing who they are and trying to get to the heart of that culture was such an important task.

AMc: So then you moved to where you are now, Boulder Creek. Am I right in thinking your home is an artists’ compound?

PS: Well, I was fortunate enough to meet this wonderful man, Dr Christopher Hills, who had published 32 books on conscious and supernutrition in the form of spirulina. Such an amazing man, and we only had three short years together. When he passed, he left me the place that he’d built here. He’d actually built it in honour of the divine feminine, which is quite an achievement for a man. He was a guru to so many people. In the latter part of his life, he found the divine feminine and felt that that was the key to our future – and quite rightly so. So he built this beautiful place in the redwood forest in the Santa Cruz Mountains in honour of the divine feminine and then looked for a manifestation of those qualities in a woman and felt that he found it in me. Over the years, I have shared this place in different ways. I held big multimedia events here for a long time and various artists in different walks of life – whether they're in music, in the visual arts or in performing arts – have come and stayed here and benefited from the energies of the place. I built a video and audio studio on the property, so we have lots of the tools we need to be able to manifest our dreams.

AMc: So you’ve continued throughout your time there to make art yourself?

PS: Oh yes, I’ve never stopped. It’s just gone through different phases. When I came here, I was very interested in the West Coast culture. I immersed myself in that for many years and worked in performance art, as well as painting and collage and sculpture, and I made a lot of videos and photography in the studio. I’ve always been interested in multimedia and this was an opportunity to explore that. Right now, I feel I’ve come full circle and my latest work ties in to my earlier work again.

AMc: In what way?

PS: Well, I’m doing a new series based on my body, but my language in it is much more black and white, starker than the more technicolour dream that I went into after I discovered tantra and became very multicultural and full colour. I went into a whole engagement with the visionary arts culture here, which is based on the psychedelic culture and therefore very complex in the imagery and very multilayered. Now I’ve come back to more of simplicity – still using all the collage techniques, but honed down again.

AMc: You’re continuing, you said, to use your own body as both the subject and object?

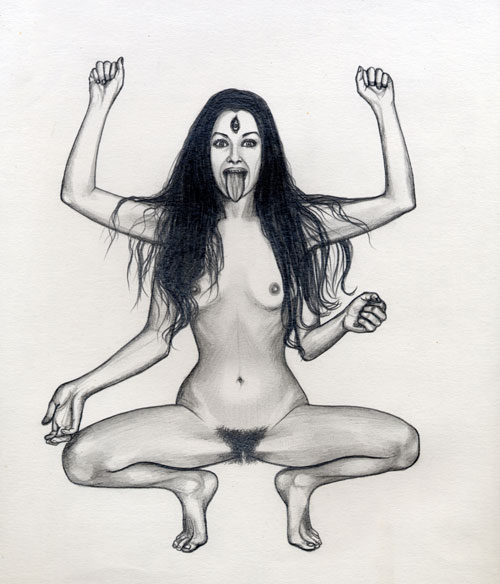

PS: I am. I’d gone away from that a little bit in my big project that I’d been working on over the past 10 years or so, the 64 Dakini Oracle. In that, I thought first of all that I could be the subject for all 64 forms of Shakti or the divine feminine, but then I wanted to include other races and their archetypes, and other women, because I wanted to share the feeling that we could all embody these energies ourselves. Now I’ve come back to distilling it into myself again.

AMc: Do you believe that women generally in art today are still too much objectified?

PS: It's been an issue throughout the history of art – the feminine form has had predominance as the muse for the artist, but generally it has been the feminine as seen by the masculine. That’s why I took this particular bull by the horns and said: “I want to be my own muse and, if I’m going to be an object, I’m going to be my own object. I’m going to see myself as a work of art and be in both places at once.” In this way, I’m not being used by anyone. I’m showing myself and the multifaceted aspects of the self. That was one of my criteria that stayed with me all my life; not being an object, other than the object you want to create yourself. It’s a different thing, really, when you’re standing in both places at once. I learned what it was like being both behind and in front of the camera.

AMc: Is that what you meant when you described your art as “a map of the journey of the self”?

PS: Yes, definitely. You’ve got to look inside because the deeper you go, the more you find that is universally true. I think we often get stuck on the surface and so what we’re seeing is something only skin deep. We see beauty as skin deep – all this superficiality of our culture, and this addiction to being seen and appreciated and liked that we’re seeing now with the whole cyber world. But if you get past that surface and go deeper and dredge up – I mean, my middle name is Delve, which is dig deeply, so I guess I got that as my birth right – if you dig things up, then yes, you’re showing something of yourself but you’re showing something that is intrinsic, something that can apply to anyone and everything and it’s way beyond being just self-obsessed and narcissistic. It’s like you’ve broken through the mirror. That has much more lasting value, I believe.

AMc:Do you see your works as sexual or is it something beyond that?

PS: When I was growing up in England in the 50s and 60s, women hardly owned their sexuality at all. Men were the sexual beings and we were the ones who just had to open our legs and close our eyes and think of England. There wasn’t any pleasure for us and, therefore, we were only firing on a couple of cylinders. As I grew up, I thought: “No, this seems completely wrong to me – we need to be able to claim our right to our own full psychosensual, sexual selves. Spiritually and materially, we need to own all of it and, therefore, be liberated from this box that we’ve been put in.” So yes, my work has been quite sexual. I felt that it was one of my missions, if you like. Doing Sexual Secrets was something that I felt called to do. I had discovered, in tantra, some powerful sexual experiences, which went beyond anything just purely physical. At first, I didn’t have anywhere that I could talk about these, but when I told Nik about my experiences, he would say: “Oh yeah, in tantra that means so-and-so and so-and-so.” So here was a liberated form of spirituality – nothing like going to church and having all the dogma shoved down your throat of what you’re not allowed to do. This was actually allowing you to have all of that without the ball and chain of shame and sin and guilt, and to express it and understand it and understand how that energy works in the body, and also to understand that that sexual energy is really no different from inspiration or spiritual realisation, it’s one energy moving up the centre of your body. It’s one powerful energy that has been so stifled. That’s why I felt it was really important to share what I had discovered with other people because it had been so liberating for me and I felt it could help liberate other people too. They might learn that they didn’t have to put things into compartments and classify them as unclean, impure.

AMc: What about the violent elements in your work – or do you not consider there to be any violent elements?

PS: In my collages, you mean?

AMc: Yes. I suppose we might talk about your work in the Hayward Gallery show, for example.

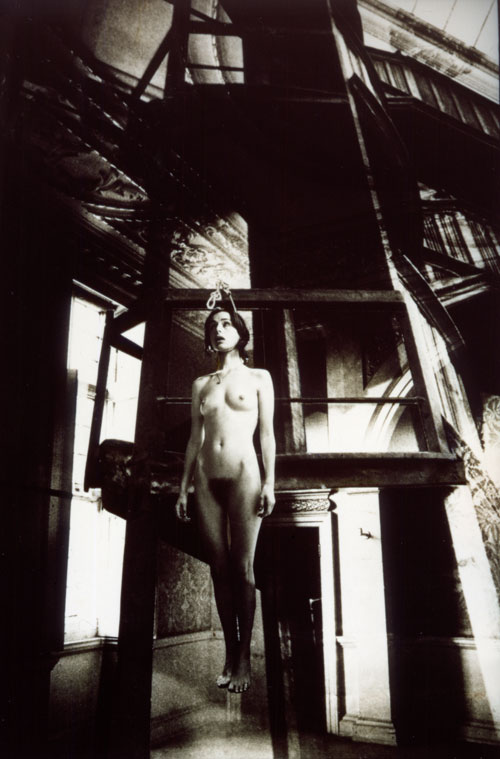

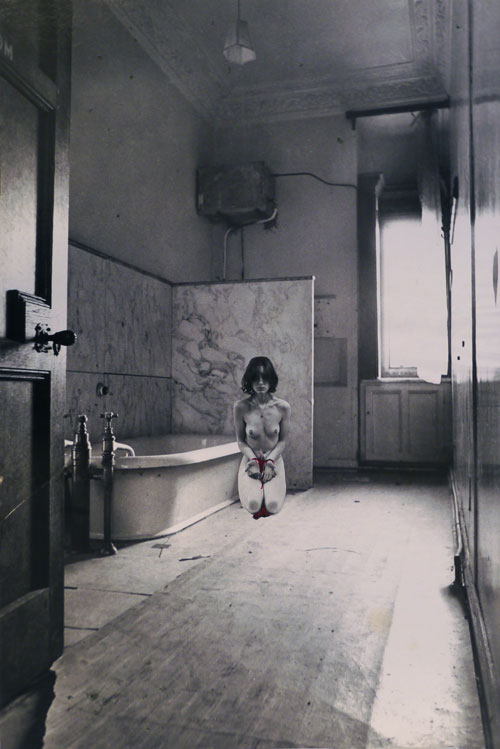

PS: Yes, the Exorcism series. Well, as I was saying earlier, I met Peter, fell madly love and we set off on a journey to work together and co-create, but it didn’t work out. When our relationship disintegrated, which it did after my involvement with the women’s theatre group, I was asking myself lots of questions about how I could have both sides of myself, my male and my female sides, and allow these relationships to flourish and function without one getting the better of the other. I went in to a breakdown and, through that, into my own process of self-analysis, which continued over a period of years. I expressed all of this through the series of collages in Exorcism. They’re simple images with titles, but what went behind each of those images was really the deep psychological work. I was trying to look at all the skeletons in the cupboard, open up all the doors in the psyche, all those taboo and forbidden places, to look in and try to confront them, and, by confronting them and bringing them to the light of day, to exorcise them in myself and, hopefully, create a path through the darkness for others who might be experiencing a similar kind of trouble in their own life and relationships. So, in pieces such as Hang Up, which is hanging in the Hayward, I was looking at things like those suicidal feelings that you can get when you’re in that kind of psychological state. I’ve never gone as far as trying to take my own life, although I did have a close girlfriend who did on a couple of occasions. That was something that really made me think so deeply: how can someone get to the point of cutting their wrists? How devastated they must be and how profound that is. So I wanted to try to explore that territory that people don’t really want to look at, to bring it to light so that it could be released and transformed.

AMc: Has anyone ever responded to your work, saying that they've related to these elements in it?

PS: Oh yes, many, many over the years. I was told by a number of people that seeing me go through it and come out the other end gave them a lot of strength and made them feel they’re not alone. And that’s the main thing. I think one of the things we suffer from so much is that feeling of isolation and that what we’re going through is our own fault somehow – that there’s something wrong with us. But if we can see that others are going through these things too and that they can survive, then it does give a lot of comfort. I think these works have given others that kind of support to help them in their darkest times.

AMc: Do you think that that is – or should be – one of the purposes of art?

PS: I do feel that art, if it’s going to be really, really good art, needs to have vision and not just be a documentation of the times. It should be something that reflects upon the times but then gives you a vision that goes beyond that. One of the reasons I’ve always loved collage is because you’re creating a new reality out of bits of known reality. It provides this freedom to be able to shuffle around all the parts of what you experience and see, but put them into new alignments and new configurations, which is very powerful and establishes you at the centre of your own manifestation rather than just being on the circumference – the cause rather than just the effect.

AMc: Again, talking about the collages that you mentioned, is that the complete series on show now, or is that just seven of a larger collection?

PS: Oh, that’s just seven out of the 99 that were reproduced in the book, An Exorcism, published in 1977. [Artist and modern art collector and promoter] Roland Penrose had been my patron for many years and he had set up an organisation called the Elephant Trust, which provided the funds to publish the book. In fact, I worked on more collages from that series and I think a couple of the ones in the show are from the larger series and not reproduced in that first volume. I went on to create what I called the “deluxe version”, which included nearly double what was reproduced in that first book. It’s almost like a film script. I did write a film script for it as well, taking you through the journey and giving more for people to chew on. That book was to have been published by Dragon’s Dream, which published my third collage book, Mountain Ecstasy, in 1979, but we got into trouble with Mountain Ecstasy and British Customs seized a whole batch that was coming in from Holland, where they were printed, and burned them as pornography. It was like a witch-burning. Dragon’s Dream got put off and therefore never produced the deluxe version of An Exorcism. I still have all the material and I’m working on trying to find a publisher now through one of my galleries.

AMc: What is the relationship between the collages and the film? Are the collages worked up from film stills?

PS: No. Here’s another very interesting story. Because of the painful breakup with Peter, that film [Lilford Hall] was just hidden in his archives, left in the can, until last year when, being in communication with him again, I managed to get him to fish it out of his archive and send it to me. We got it digitised and that’s how I have it now. But it wasn’t touched in all those years, since 1969.

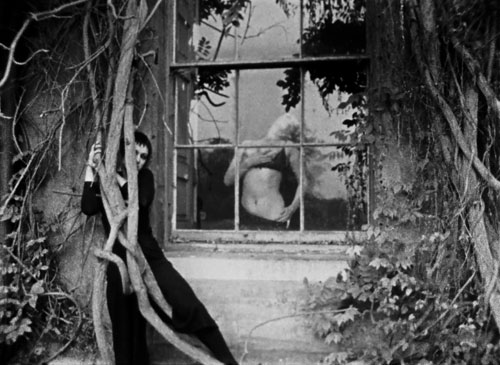

Lilford Hall was this big mansion house in Northamptonshire where Peter had stayed when he was a student but which was, by then, completely derelict. We went on a magical mystery tour to find it and got permission to film and take photographs. The film, as I say, stayed in the can, but we took photographs at the same time. We walked around the whole house and grounds and took all these beautiful black-and-white photographs. I then took those negatives – I had my own dark room – and printed up all the photographs and did some montages, which is what we see in the book. They became the basis for the whole series of collages, which I worked on post our relationship, trying to process all the energies that had arisen in that time. They were the set for the drama that I then unfolded through the series of collages.

A young man is making a documentary of my earlier work at the moment and he managed to get access to Lilford Hall and he’s gone back and shot there recently. He’s just sent me the rushes and it’s still empty, but certain rooms are being restored. It’s very interesting to see the personality of this beautiful big mansion house and the changes it’s gone through.

AMc: I can imagine. Were you surprised last year by the content when you rediscovered your film? Was it what you remembered it to be, or were there any elements that you’d forgotten about?

PS: I hadn’t remembered exactly how it was, but certainly the mood and the mode of everything was there. A lot of the themes that I’d worked with, both before and after, featured in the film, so it gave a wonderful sense of continuity. It was so good to see it again after all this time. I haven’t touched what came out of the can, just because it felt very right like it was. I may do something with the material in different ways, but I really like it as it is because of its repetition. When you’re doing rushes and you’re doing the same scene over and over again, it just feels like you are looping time and that seems very much in tune with the message that we were trying to get across.

AMc: How do you intend people to watch it in the gallery? It is, as you say, very long – 74 minutes and 53 seconds – and it’s just being projected on to a busy gallery wall, without any seats.

PS: I just thought people would probably drift through and see a bit here, a bit there, because it has that dreamlike, repetitive quality. It is something that one can just drift in and out of, which made me feel that it was quite suitable for a gallery showing. That’s also why I didn’t add sound to this particular version. I’ve shown it in the Blum and Poe Gallery in Los Angeles as well. It had its own room there, but I kept it silent too, to go with the exhibition.

AMc: The section in the Hayward Gallery where your works are being shown is curated by Jane and Louise Wilson. How did it come about that you were included? Did you know them already?

PS: I didn’t and I’m just getting to know them now. It wasn’t anything that happened through a personal connection. They went to LA and saw my work at Blum and Poe and then they came back to England and saw my work at the Riflemaker Gallery in London. So it’s through the galleries that they became familiar with my work.

AMc: Talking about their section of the show, they have said: “We’re interested in … crossing thresholds, and stepping across perimeters and entering different zones.” Is this something that you would identify with in your own work, or with yourself?

PS: Definitely. As I was saying earlier, breaking out of the box is something that I have been dedicated to doing all my life. My whole exorcism is really to do with opening up different doors and going through into different zones, going through the boundaries that have been established by society or culture. Of course, that’s very much in the surrealist tradition, too – breaking through into the unconscious and not being stuck with the mundane reality that we’re normally faced with or with the categories that things are put into in life.

AMc: Your school report, when you were 10, included the comment: “There are 36 children in this class; 35 going one way and Miss Slinger going the other.” I thought that was wonderful.

PS: Yes, it sums it up. And, you know, when you grow up and you feel you don’t really fit in, you can either feel that you’re some strange, lesser-than person, or you can feel that you’re special. Luckily, I had a family, a mother and father, who helped me feel I was special – even though they didn’t understand me really – and not some weird freak. I think that’s a really important and strong foundation to have, that you can feel it’s all right to be different. I don’t think being different is something you choose – it’s just who you are. What you do with it is up to you.

AMc: You talked before about the levels of subconscious and superconscious. Can you expand on that a little?

PS: I was fascinated to find that the kind of language, visual language, that comes out of dreams and out of the subconscious is so close to the language of those enlightened beings in their beautiful tantric artworks, whether it was out of the Tibetan tradition, where they create these amazing works of complexity, thangkas and mandalas, or whether it was from the more direct yogic art, which showed these transformed humans. I think the essence of it is that I’ve always been fascinated by the human form because we come in a human form and we can all identify with this image because it’s the closest thing to us when we manifest in this world. But I wasn’t so interested in the human form just in a representational kind of way, but much more in a symbolic way, in showing the potential that it has to transform into all kinds of other things. We find that both in the language of the subconscious, but also in the language and in the art of the superconscious, the higher realms of consciousness where there’s potential to manifest in all kinds of different ways.

This bridge between those two realms is the one that I’ve been walking back and forth across throughout my life. I think this is where the divine feminine, as opposed to the masculine face of the divine that we’ve had for so long in our culture, comes in, because she merges the material and the virtual. She says that spirit is in all of matter and so it gives an incredible freedom to be able to play with this material that we have, in this case the human body, in a way that is not limited. It can become the sky, the sea, the air, the birds, the flowers. We are all of that and it’s in all of us. It’s something magical and transformative and mythic. I do believe, along with [the American writer and mythologist] Joseph Campbell, that we should live our mythic life. This is what I’m talking about with the subconscious and the superconscious – that this is all part of the mythic weave where you weave your dreams into reality.

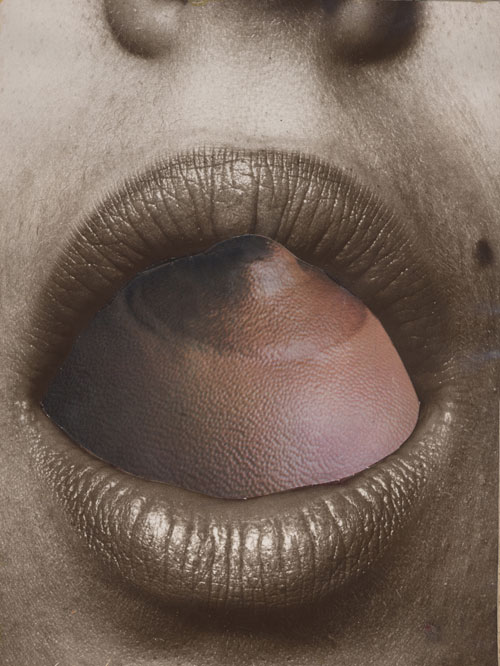

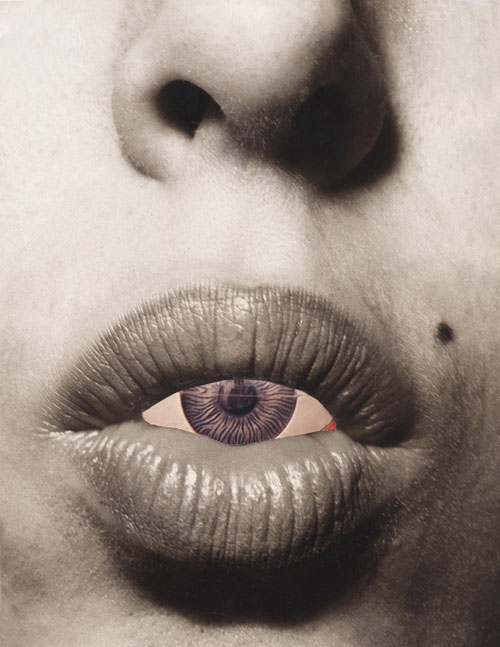

AMc: Again, using the collaging, and with the work that was on display at Riflemaker in 2012 in the exhibition Hear What I Say, where you’ve got the repeated motifs of the mouth and the tongue and the nipple – is that about embodiment or disembodiment, or just showing that everything is everywhere, as you were just saying?

PS: Well, the mouth pieces came from a particular series which was part of an exhibition in 1973, most of which has now disappeared because it was bought by a woman collector who took it away into her black pyramid. I can’t track down what’s happened to it and I can’t reach her now, although I know she’s still alive. It was a series of erotic tabletops and I worked with both life casts and photo collage. I had a number of 3D life casts of mouths and then whole bodies, which I transformed into tabletops. The subtext of the exhibition title, Opening, was “I’m hungry, I’m not getting enough nourishment. All I get is food to feed my belly; what about everything else?” I was looking at the whole relationship between food and eroticism, nourishment and the feminine and what feeds this and what doesn’t. The mouth pieces were all around trying to give a voice to the feminine and saying we have no voice. I was showing both the things that have bound and restricted it and also the things that would liberate it. For instance, the mouth with the eye within it is trying to bring together those different organs of sensation and cognition and question how we feel, articulate and communicate. By bringing them together, I wanted to create a kind of shockingness to wake people up. In my earlier work, I was very keen on that shock of recognition, getting attention by doing something that would jar people’s perception in some way by bringing disparate things together. As the surrealists said, the sewing machine and the umbrella on an operating table, what do they do? They make love. So I was trying to bring things that normally wouldn’t make love to make love together.

AMc: It’s curious because the press over here keeps talking about your being rediscovered a couple of years back, but it sounds from everything you’ve been saying as if you never stopped making art, and even showing art?

PS: That’s right. I had this obviously mistaken idea that everything I’d done before was of real and lasting value, so even if I left England, the recognition of that work wouldn’t stop; it would be there for all time. But then I realised that’s not it at all. Out of sight, out of mind. So for all my sojourn over here, which I just saw as an evolution in my own artistic career, I was just lost. Even my early work had been basically lost to the annals of the art world.

My first opportunity to show in the UK again came through the exhibition Angels of Anarchy at the Manchester Art Gallery in 2009. I loved being in that show, even for the title alone. It was a wonderful exhibition of female surrealists and some of my work from the late Roland Penrose’s collection was included, thanks to his son Antony, who now looks after it. This stirred some interest again, completely through the auspices of a fellow collagist, Linder Sterling, who loved my work. I hadn’t met her before, but she had seen 50% The Visible Woman, my first book, way back in the 70s, and it had been that book that had stimulated her whole artistic career. Unlike so many other artists, who tend to be so wrapped up in themselves that they can’t see beyond the end of their own nose, she, being a much bigger person, was instrumental in helping to connect some dots for my work to get shown again. At the time that the Anarchy exhibition was coming up, she showed my work to some people who were organising a show called The Dark Monarch at Tate St Ives, and they included some of my pieces in that exhibition too.

So these exhibitions happened and I was able to come over for the openings and that stimulated interest from Riflemaker, which had been looking at my work for a long time, and seeing it now come back into the light of day, it decided it wanted to do something with me. So I got the opportunity to re-enter, and I was delighted to be back because my work had disappeared from the scene. It’s disappointing when you feel that you’ve made a real contribution and then suddenly, like I say, out of sight, out of history. But all that now is turning around and I’m pleased because it also gives me an opportunity to work with one of the other things that I’ve wanted to work with for a long time, which is the whole issue of how, when people get older, especially women, they are seen as no longer being useful parts of society. It’s one of the crimes of society, I believe, that a lot of mature people don’t have the ability to give their wisdom and their experience back into society or have any position of weight or power. They just fade away, sad and disappointed. Now in my wise woman years, I feel it is really important to be strong and energetic and meaningful.

• Some of Penny Slinger’s works are included in Jane and Louise Wilson’s section of the Hayward Gallery exhibition, History is Now: 7 Artists Take on Britain, 10 February – 26 April 2015