Paula Rego in her studio with two of her Seven Deadly Sins, Gluttony on the left and Pride on the right. © Nick Willing.

by JULIET RIX

Paula Rego is not necessarily thought of as a political artist. With so much of her work drawing on stories – folk tales, myth and characters from literature (sometimes in surreal combinations) – her reputation is more for subverted narrative than protest. But her art has been political from the start.

Born in Lisbon in 1935, Rego grew up under the fascist dictatorship of António de Oliveira Salazar. Her father secretly printed anti-government leaflets, and paintings such as Salazar Vomiting the Homeland (1960) made Rego’s own views on the subject riskily clear. Her enlightened father sent his only child to England to finish her education and supported her against her headmistress in her desire to go to art school. She attended the Slade in the 1950s, alongside Frank Auerbach and David Hockney.

Paula Rego, Salazar Vomiting The Homeland, 1960. Oil on canvas, 94 x 120 cm. © Paula Rego Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art.

While still a student, she met the, older, already established, and married, artist, Victor Willing. Their first encounter became family folklore, usually told by Rego as romantic, although their son, Nick Willing, says that when he heard it again as an adult he realised it was “actually closer to rape”.

Victor was probably the most important influence in Rego’s adult life, and on her work, at least until some years after his death from multiple sclerosis in 1988. In Sleeper (one of the Dog Women series), it is Willing’s jacket on which the woman lies, the woman modelled by Lila Nunes – Willing’s, then Rego’s, long-term assistant, who often represents Rego herself in her paintings.

Paula Rego, Angel, 1998. Pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 180 x 130 cm. © Copyright Paula Rego, Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art.

Nick thinks that his close resemblance to his father is one reason his mother opened up to him so much in the intimate film he made about her in 2017. It explores his parents’ relationship, along with Rego’s struggles with depression. It is essential viewing for anyone interested in her work and is on show in the MK Gallery exhibition.

An A-list celebrity in Portugal, with her own museum since 2009, Rego really took off in the UK with her Serpentine Gallery show shortly after Willing’s death. She became the first National Gallery Associate Artist from 1989-90, and is now represented in top public collections including the Tate, the Gulbenkian and the British Museum. Rego is one of today’s most admired figurative artists and, although now in her 80s and despite a recent stroke, she continues to work in her north London studio.

Juliet Rix: How does it feel to have this 80-picture retrospective showing in England, Scotland and Ireland?

Paula Rego: Well, I’m very honoured.

JR: The exhibition focuses on your more political work, beginning with your opposition to the fascist dictatorship in your native Portugal.

PR: Both my father and my grandfather were political. My father was an anti-fascist and my grandfather before him was a republican and anti-monarchist. I was aware of the country I was growing up in. It wasn’t a democracy. My father was a great admirer of Great Britain and we had many English books in the house. We’d listen to the BBC every day to find out what was going on. My father didn’t live to see the revolution that would transform things.

Paula Rego, Centaur, 1964. Oil, graphite, and paper on canvas, 140 × 139 cm. © 2019 Paula Rego and courtesy Marlborough Fine Art.

To a great extent, I was protected because my father had an engineering company and we weren’t poor. The poor starved, particularly in the countryside. There were political prisoners who were tortured and imprisoned. You had to be careful what you said.

During the second world war, Portugal was neutral, which meant many people came through the country. Jews escaped through the country. [António de Oliveira ] Salazar had an affinity with other fascist dictatorships, but was not particularly interested in punishing Jews.

The place was crawling with spies from all sides. The Germans favoured the hotel Atlantico. The Duke and Duchess of Windsor stayed down the road in the Palacio Hotel. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry came and gambled at the casino. It was an interesting time.

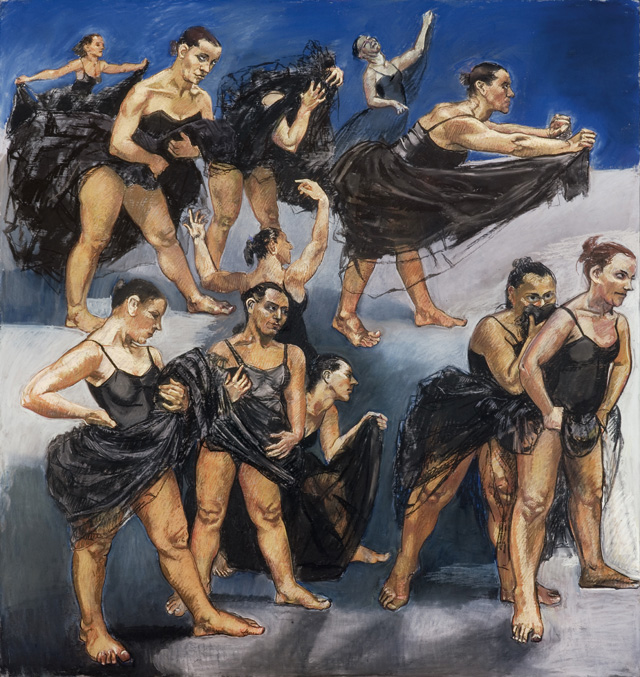

Paula Rego, Dancing Ostriches, 1995. Pastel on paper mounted on aluminium (left panel 162.5 × 155 cm). © Paula Rego. Courtesy of The Artist and Marlborough, New York and London.

JR: You told me once about the domestic violence and the lack of voice abused women had in Portugal at that time. Can you tell me a bit about your memories of that – and how that came into your art?

PR: Dictatorships are violent in themselves. Domestic abuse takes place everywhere, though, and in every part of society. What was different was that beating your wife was taken completely for granted. Women were the property of their fathers and then their husbands. No one came to help them. They didn’t expect it. There was a family who lived on the hill above our farm. He was a miller and he was forever beating his wife. We could hear the screams from our terrace. One day, Luzia, our housekeeper, found the woman trembling behind a bush with all her children cowering around her, “like a hen with her chicks”, she said.

JR: Do you think growing up under such conditions helped make you the artist you became?

PR: I have no way of telling, but it gave me subject matter.

Paula Rego, Untitled No. 5, 1998. Pastel on paper, 110 x 100 cm. © Paula Rego Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art.

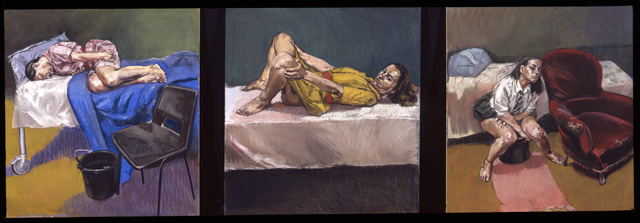

JR: The exhibition includes the particularly raw and powerful pictures about the effect of illegal abortions that you produced in 1998, at the time of the abortion referendum in Portugal – pictures that became part of the public discourse. Does it make you proud that your work had an impact on public perception of the issue?

PR: Yes.

JR: The pictures are very visceral.

PR: I didn’t put in the blood. I was focusing on what the women felt.

JR: Of course, I meant visceral in feel rather than image. You have had several abortions yourself. How much of your own experience went into these pictures?

PR: Not a lot, more of what I heard of.

Paula Rego, Triptych, 1997-8. Pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, each panel 110 x 100 cm. © Paula Rego Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art.

JR: Just this week the foreign secretary, Jeremy Hunt, who is running for the Conservative party leadership, said he personally favoured only allowing abortions up to a maximum of 12 weeks’ gestation. What would you say to him?

PR: Jeremy who? Good lord. Women don’t choose to have abortions late if they can help it. A tiny percentage have to, and mostly for medical reasons.

JR: And how do you feel about what some states in the US are now doing, rolling back the right to abortion?

PR: No matter what the lawmakers want, women will still have them, just like they used to in Portugal and England when it was illegal. What the lawmakers are doing is putting the women in danger.

JR: There is a lot about gender relations and violence against women in your art. Some of this also seems to combine the political and the personal. Your husband, the artist Victor Willing, was not an easy man, was he?

PR: He was not a violent man. He was a brilliant intellectual and a talented man. He was very handsome and a very good dancer. I fell in love with him. That’s hard to explain. He was very good at painting and knew a lot about it and how to make it. He encouraged me. He supported me in my work and he wasn’t jealous of it. Why would he be when he was so good himself? I still miss him.

Paula Rego, Dancing Ostriches, 1995. Pastel on paper mounted on aluminium (right panel 160 × 120 cm) © Paula Rego. Courtesy of The Artist and Marlborough, New York and London

JR: Who coined the exhibition’s title, Obedience and Defiance? Do you feel it sums up much about your work?

PR: The title was a collaboration between myself and the curator Catherine Lampert. I suggested the Obedience part of it.

JR: Your curator says that your work is often “concerned with a struggle against domination, both sexual and political”. Would you agree?

PR: Personal and political, maybe. Sex comes into it because it’s part of life … I’m interested in seeing things from the underdog’s perspective. Usually that’s a female perspective.

JR: When you make a work, are you conscious of what you are trying to say with it. I mean, is there a message in your mind, or does the work take over at a certain point?

PR: The abortion pictures and the genital mutilation prints had a cause in mind. They are very focused on that. Things creep in to other works. I start a picture and finish off doing something quite different. I discover what it’s about over time. Sometimes much later.

Paula Rego, Disgust, 2001. Pencil on paper, 42 x 29.7 cm. © Paula Rego Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art.

JR: You have talked in the past about using art to come to terms with things in your life, or to “turn the tables” on people who have treated you badly.

PR: I realised that in your work you can do anything. You don’t have to stop yourself. I do the opposite of self-censorship. I was able to take my revenge on a very cruel teacher who terrified me as a child [in School for Little Witches]. She taught me the times tables, and she made me feel bad about my drawing. She said: “Look at this girl, who says she wants to be a painter, and look at the rubbish she draws.” I was supposed to draw a cup and saucer. It was very difficult and not very interesting. I couldn’t do it now.

I cast nasty people as nasty characters, bullies and witches and so on. I use them in scenarios and take pleasure in their downfall. They can be skewered or hung or shown for the repellent creatures I feel they are. You can be as violent as you like in a picture.

Paula Rego, The Cake Woman, 2004. Pastel and paper mounted on aluminium, 150 x 150 cm. © Paula Rego Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art.

JR: How essential is making art to your identity?

PR: Totally. It’s what I do. I don’t know how to do anything else.

JR: And to your survival?

PR: Yes.

JR: Does drawing and painting come easily to you, or do you really have to work at it?

PR: Sometimes, it comes easily and sometimes it’s very, very difficult. But I always try to draw with pencil and paper to get things going. To keep going till I get an idea.

JR: You use a lot of mythical or literary elements to approach your subjects. Does a story make it easier for you?

PR: A story is essential for me.

JR: And perhaps easier for us as viewers to approach difficult and disturbing subjects?

PR: No, it has to do with the artist themselves, not the viewer.

JR: Does it also extend things from the particular to the universal?

PR: The only pictures that were calculated in this way were the abortion pictures. Some subject matter is universal. Folk tales that have been around for hundreds of years, or religious stories, resonate collectively.

Paula Rego, The Exile, 1963. Mixed media on canvas, 152 x 152 cm. © Paula Rego Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art.

JR: Do you often find inspiration in film and theatre as well as books? What makes a story speak to you, do you think?

PR: I have loved film ever since I was a child. I used to watch a film every day when I was at the Slade. Watch a film and eat a family pack of Wall’s ice-cream. I can’t say what will grab me. I just know when it happens. I used my love of Disney films as inspiration for the [1996] Spellbound exhibition at the Hayward gallery.

JR: Your powerful Pillowman triptych came from seeing a play at the National Theatre …

PR: It was done after seeing the play The Pillowman, by Martin McDonagh. In it there were small plays – a play within a play. One was about a little girl who wanted to be Jesus, and I identified with it for some reason. It was a marvellous play, with thrilling transgressions. My trilogy is not an illustration of the play. It just moved me immensely. I used the little girl and her homemade cross. I set it in Portugal, in Estoril, on the beach.

JR: I understand you started corresponding with McDonagh?

PR: The picture was shown at the Tate and Martin McDonagh came to see it and gave me a bunch of short stories that he usually gave to his actors to put them in the right frame of mind. I made a picture from each one of the stories. Like: The boy with turtles for hands.

JR: You have said that the Pillowman is a depiction of your father’s depression and, I have to say, it is highly evocative.

PR: My father was a depressive. Sometimes, he wouldn’t speak for days. But everybody loved my father. Everyone: the people he worked with, the maids, everyone. He was very funny and a practical joker. He’d tease his friends. If people came to dinner and it was getting late, he’d turn to my mother and say: “Maria, let’s go to bed because these people want to go home.”

Paula Rego, The Maids, 1987. Acrylic on paper on canvas, 213 x 244 cm. © Paula Rego. Courtesy of The Artist and Marlborough, New York and London

JR: You have suffered from depression yourself. You have spoken of “drawing your way out of depression”, particularly with a series of drawings that only recently came to light. How important has your art been in dealing with depression?

PR: For me, working is the best way to get through depression. A shrink can also help. When you are in a depression, you feel like it might last for ever. Sometimes it does. Besides my father being a depressive, my great-aunt was nearly given a lobotomy to try to get her out of hers. It didn’t help that her husband lived in the flat next to her with his mistress.

Paula Rego, Dog Woman, 1952. Pencil on paper, 15.5 x 21.5 cm. © Paula Rego Courtesy Marlborough Fine Art.

JR: Your powerful mid-90s Dog Women series is quite – deliberately? – ambiguous, and perhaps ambivalent, about the role of the woman as the master’s dog?

PR: They were about an emotional connection. An emotional dependency and love. And the physical sensation of loss and missing. The physical connection, too. The animal quality of that longing.

JR: Your pictures are often, as Lampert points out, of real women. You don’t gloss over or glamorise. How important do you think that is?

PR: I paint what I see.

JR: Do you consider yourself a feminist?

PR: In the sense that I have defended women’s right to safe abortions and made work about female genital mutilation. I make work from a woman’s perspective, but that is because I am a woman. It would be hard to make work from a man’s perspective.

Paula Rego, War, 2003. Pastel and paper mounted on aluminium, 160 x 120 cm. © Paula Rego Tate: Presented by the artist (Building the Tate Collection) 2005 Photo: © Tate, London 2019.

JR: The most recent work in the exhibition is Painting Him Out (2011). It has been suggested that it is about the obliteration of male authority?

PR: It’s from a story by Balzac The Unknown Masterpiece. I don’t think it is [about the obliteration of male authority]. The painter is always in charge of her painting. She decided to paint him out. She changed her mind.

JR: How much do you think the position of female artists has changed since you started working? How hard was it for you to be an artist?

PR: Hopefully, things have changed a great deal. There seems to be less discrimination. It wasn’t hard for me to be an artist, but it was hard to sell my pictures and get a gallery.

JR: For some time, you worked in London while your children remained in Portugal – and this was encouraged by a large grant-giving body. Did that separation affect you or your work?

PR: No.

JR: We last spoke when your son Nick’s marvellous film about you was about to be released, in 2017. Do you think the film has made a difference to how you or your art are understood?

PR: I think it did make a difference to how people understood my work. It’s a very good film. It’s right.

JR: Did the process of making it have any effect on you or your art?

PR: Not at all.

JR: Who do you most admire among other artists?

PR: Francisco Goya, James Ensor, Edward Burra.

JR: Who, or what, inspires you now?

PR: Stories still inspire me. I’m always looking for new stories.

JR: Are there any issues today that you feel strongly about and are finding their way into your art?

PR: I’m not working with issues.

JR: What are you working on at the moment?

PR: I’m working on the seven deadly sins.

• Paula Rego: Obedience and Defiance is at the MK Gallery, Milton Keynes, until 22 September 2019, then at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh (23 November 2019 – 26 April 2020), and the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin (25 May – 1 November 2020).