reviewed by BETH WILLIAMSON

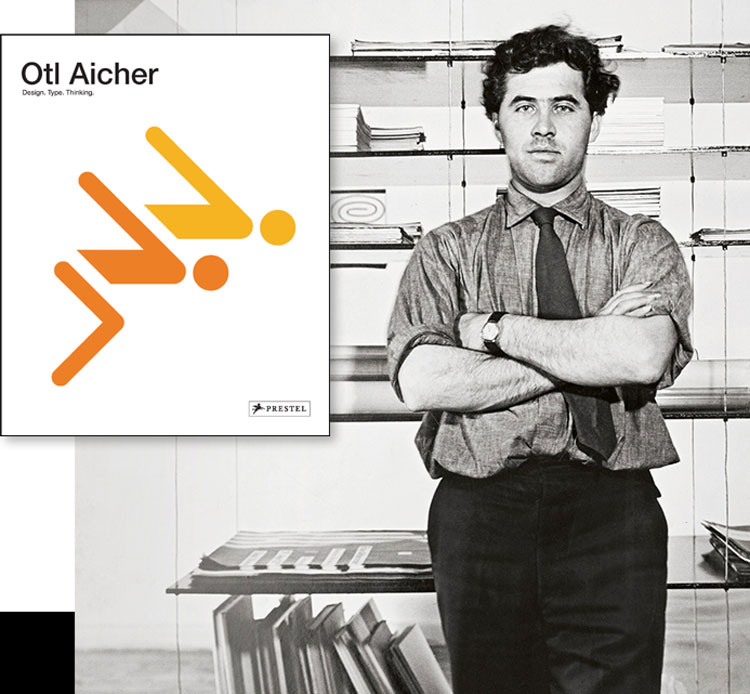

You may not have heard of the German graphic designer and typographer Otl Aicher (1922-91) but you may well recognise the iconic posters for the 1972 Munich Olympics, for which he led the design team. Aicher also cofounded the famous Ulm School of Design (Hochschule für Gestaltung, HfG) in 1953 and taught there during the school’s 15-year existence. This beautifully produced publication examines every aspect of Aicher’s career from design to teaching, architecture, photography and typography. As this book shows, his influence on corporate identity, or what he called the visual appearance of companies, was significant. It brings together his writing, thinking and making, to demonstrate how all those things reflected on the political, cultural and social climate of his day.

[image5]

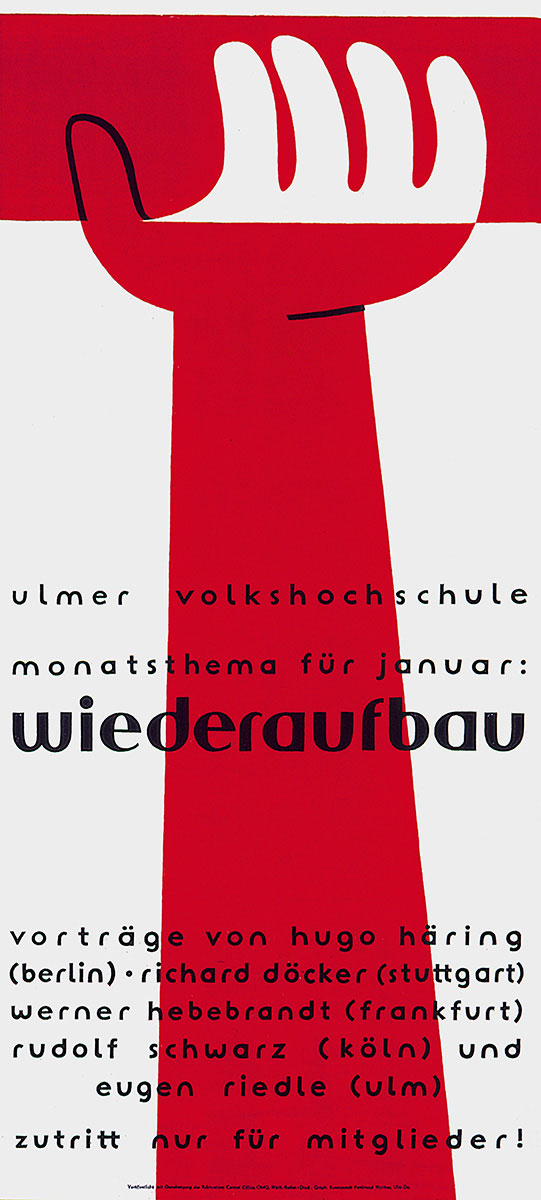

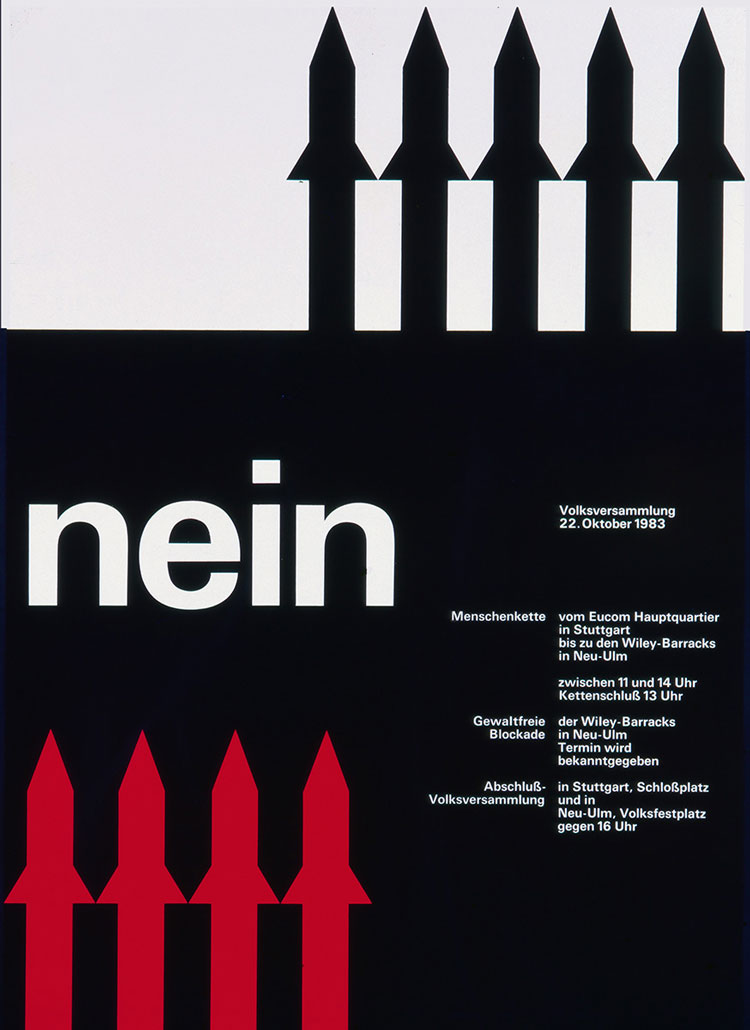

Thinking and making went hand in hand for Aicher from the very beginning. As a schoolboy, he was already reading philosophy and soon developed a philosophical mode of thinking that underpinned his design and making more broadly. For him, there was also a moral imperative for those who design consumer products, a responsibility to the public. He understood his responsibility as a designer as the constant endeavour to build a new and better order. Aicher believed fervently in the freedom of the individual and firmly opposed the politics of Nazi-era Germany – he called this “thinking against Hitler”. The hope for renewal after the fall of fascism came, for Aicher, in the form of education. He co-found the Ulmer Volkshochschule in 1946 and proposed Studio Null the following year in 1947. He already had the idea for the Ulm School of Design in 1947, although it would be another six years before it opened.

[image3]

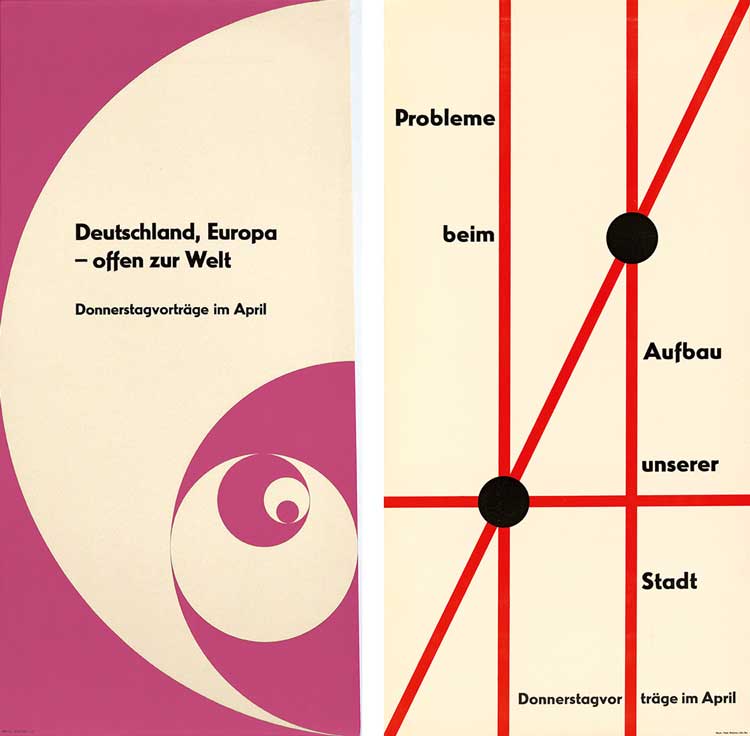

Teaching at Ulm revolved around two things. First, development groups linked to industry and, second, a scientifically based design education. Aicher’s ambition was for Ulm to be a centre for cultural and societal development. The idea was to educate a group of people who would go out into the world and change it for the better. Aicher is painted as someone who stuck firmly to his convictions about what design education should be, even when he was, at times, at odds with some of his peers. This is an enthralling chapter and one that is especially enriched by the use of archival images.

[image12]

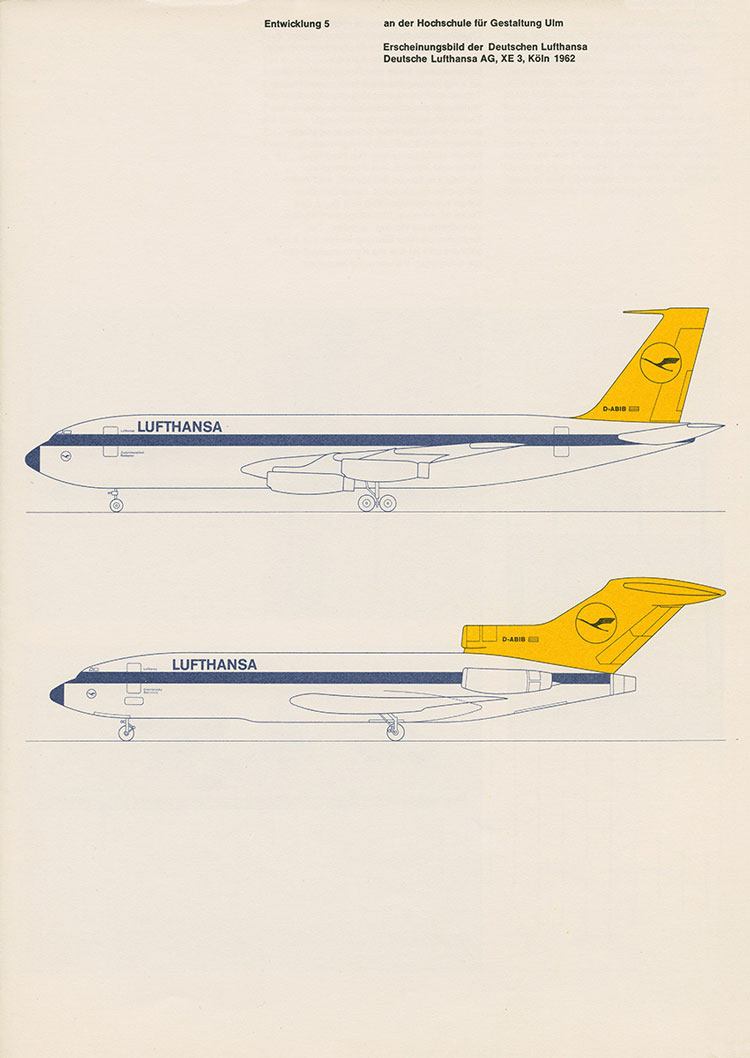

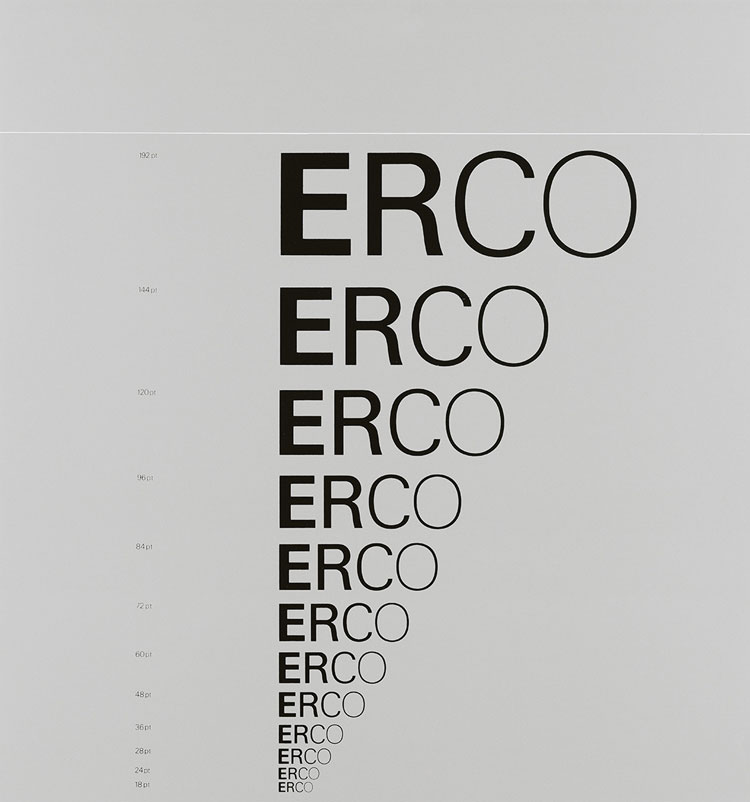

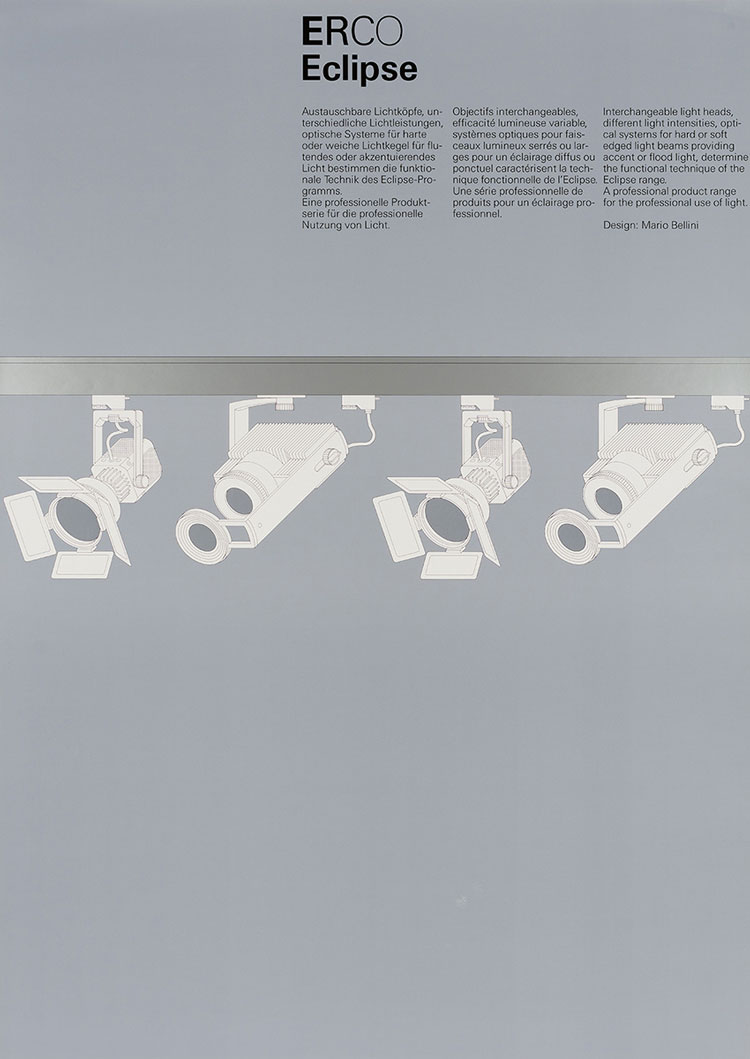

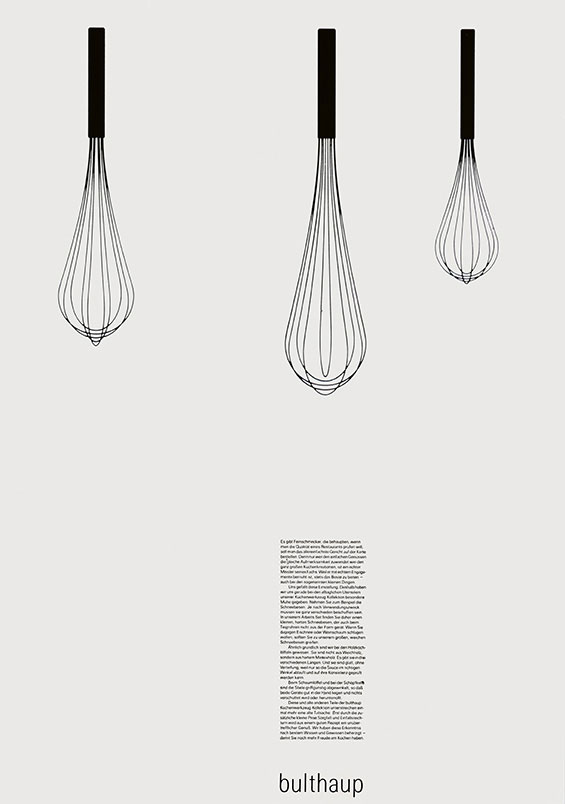

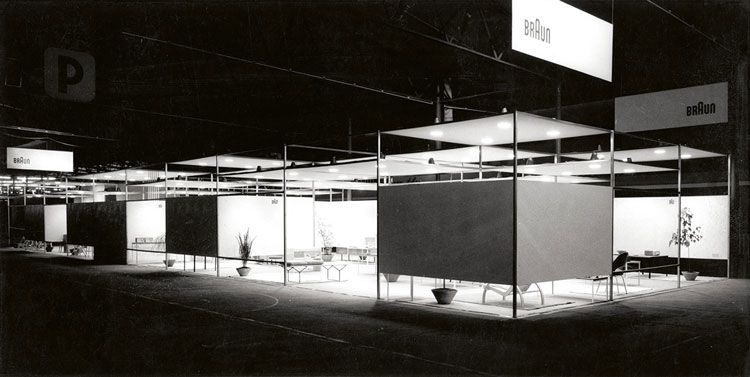

Aicher developed notable designs for Braun and the airline Deutsche Lufthansa in the 1950s and 60s, helping to put West German design on a par with companies such as Olivetti and Sony. Wolfgang Sattler’s essay on industrial design asks pertinent questions about Aicher’s continued relevance in the age of digitalisation and user experience (UX), for instance. Sattler suggests that the practice-oriented training developed at Ulm has had a lasting impact, showing how that plays out in different ways, including in some Apple products. Aicher’s visual thinking is seen in architectural spaces, too, in the Erco lighting for Stuttgart’s public library and the corporate design for the Dresdner bank, for instance. His corporate image for Deutsche Lufthansa is one of his best known, but other related designs, such as that for the Lufthansa on-board tableware, he entrusted to Hans “Nick” Roericht. I found it fascinating to learn the level of detailed decision-making involved in selecting the colours and materials for this project, as well as the several thousand colour samples created for another project, with BASF.

[image6]

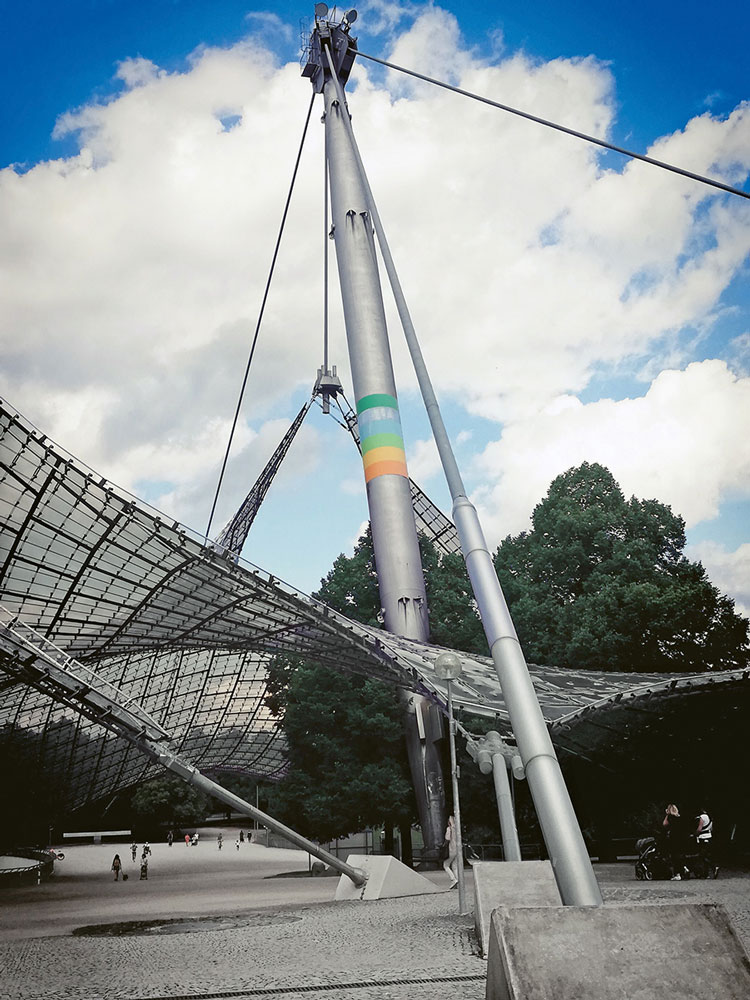

The visual appearance of the 1972 Olympic Games – the rainbow colours, the pictograms, the street furniture – everything evolved from initial conception to final realisation. The pictograms for sports and services were an important mode of visual communication that cut through the complexities of global communication needs. Aicher and his young team changed the face of graphic design as the “Cheerful Games”, as they were known, were brought to life.

[image17]

Aicher was also an architect, exhibition designer and photographer. From the Braun trade fair stand for the German Radio Exhibition in Düsseldorf in 1955, to the sawtooth roofs of studio buildings in Rotis, or his photographs of rhythmic winter landscapes, all of these show different aspects of Aicher’s capabilities. His reach extended beyond even these activities as he designed books and book jackets, experimenting with type, typefaces and page layout.

[image15]

[image8]

I appreciated everything about this book. It is beautifully designed with a nicely balanced mixture of text and high-quality images throughout. Images are key for this sort of book, but thoughtful and thoroughly researched text is, too, and there is no shortage of that. The essays are well written, building arguments carefully and, between them all, building a picture of Aicher as highly committed design practitioner of extraordinary achievement. While essays are grouped together in helpful thematic sections, they nearly always refer back to his time at Ulm School of Design and, from there, to his fundamental belief in the interdependence of thinking and making. This recurrent backward reference is not repetitive, but acts as a light unifying thread through the book. Neither is it, to my mind, about being in thrall to the past, but about making sense of different developments in Aicher’s life and work in order to understand his continuing importance. Aicher’s relevance in contemporary times endures despite huge paradigm shifts in the field of design. The last word must go to someone who knew him, the architect Norman Foster, who called him the best designer in the world. Quite an accolade.

• Otl Aicher: Design. Type. Thinking., edited by Winfried Nerdinger and Wilhelm Vossenkuhl, is published (UK: 7 June 2022; US, 5 July 2022) by Prestel, price £45/ $60.