Wolfson Galleries, Charleston House, East Sussex

8 September 2018 – 6 January 2019 (Weds-Sun)

by ROSANNA MCLAUGHLIN

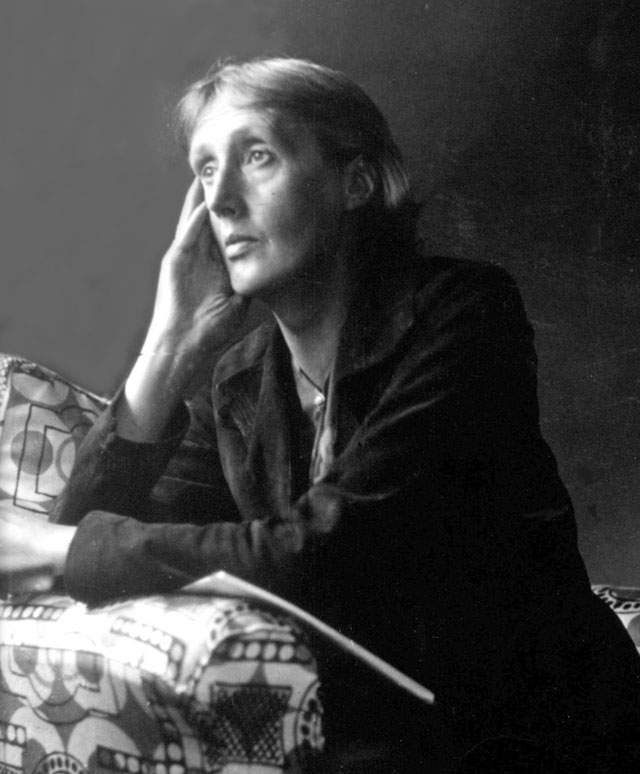

In 1916, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, along with Bell’s children and Grant’s lover, David Garnett, moved to Charleston, a farmhouse in a verdant corner of East Sussex. Over the next 64 years, Charleston would become the country retreat for the Bloomsbury Group, and an artwork in its own right – the interior design as much part of Grant and Bell’s oeuvre as any of their paintings. Today, the house is a site of pilgrimage for fans of Bloomsbury’s bohemian strain of intellectual charm. Tours of the house alone are worth the visit, particularly for those with a soft-spot for biographical trivia. The staff are so well versed in anecdotal history that one would not be surprised to hear what kind of eggs Vanessa Bell served John Maynard Keynes for breakfast, or which day Virginia Woolf was allotted on the weekly bath rota.

[image18]

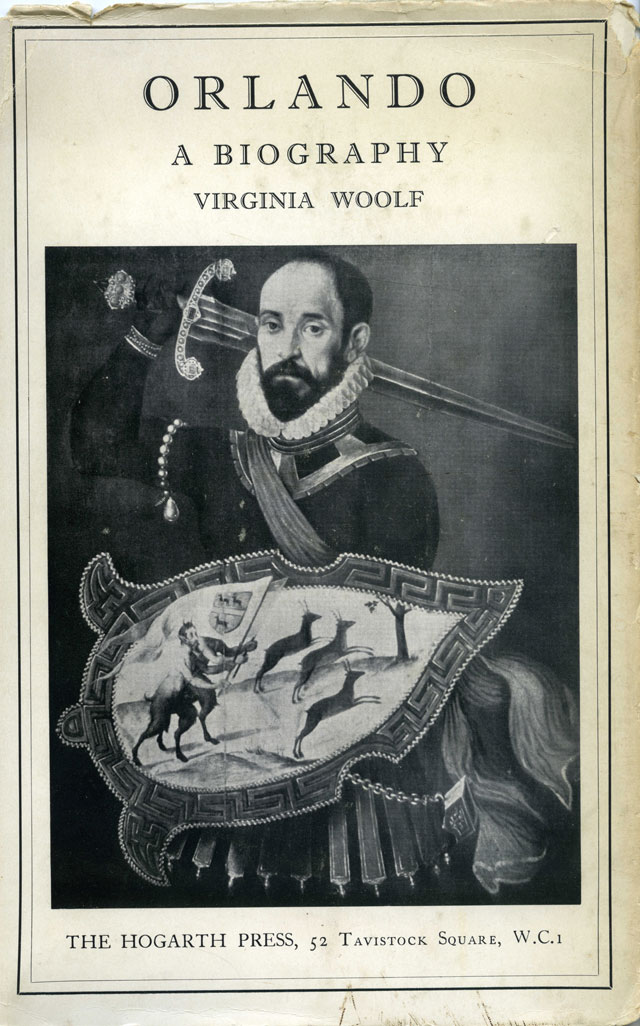

This September, Charleston has opened three new spaces: two converted 18th-century barns, which function as a restaurant and events hall; and a newly built exhibition space, consisting of the Wolfson and South galleries. Among three inaugural exhibitions in the galleries is Orlando at the Present Time, which takes for its theme Woolf’s 1928 novel. A historical canter through histories and genders, Orlando is widely viewed as a billet-doux to her lover, the poet and aristocrat Vita Sackville-West.

[image6]

On display in the Wolfson Gallery are a number of paintings and photographs selected by Woolf and Sackville-West to illustrate the original version of the book (enough to raise the pulse of any Bloomsbury scholar). Hanging near the entrance is a 17th-century double-portrait by Cornelius Nuie of Sackville-West’s ancestors Richard and Edward Sackville, used in the book to depict Orlando as a boy. At the far end of the gallery is a painting by an unknown artist from the early 19th century, found by Woolf and Sackville-West in an antique shop in nearby Lewes and used to illustrate Orlando’s lover, Marmaduke Bonthrop Shelmerdine, Esquire.

[image3]

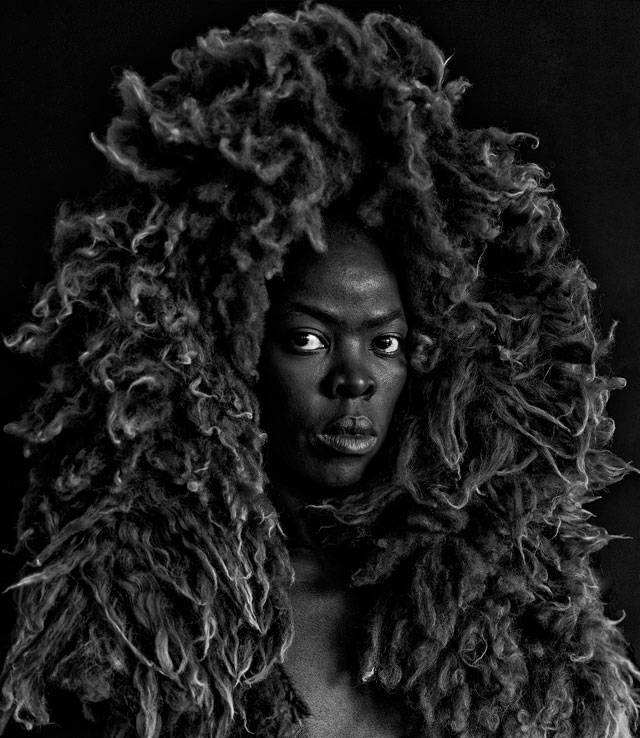

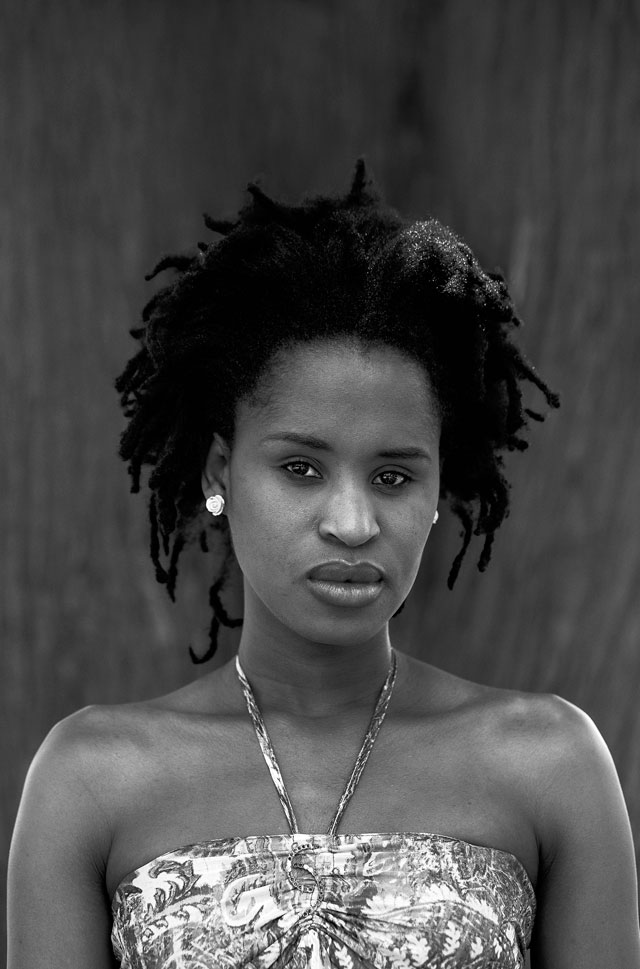

Alongside these historical gems, contemporary artworks are dotted about, in an attempt to show Orlando’s relevance today. Among them are Our Tears for Smiles and The Eclipse That Settled (both 2018), two gorgeous oil-on-linen portraits of ghostly women by Kaye Donachie; some garishly coloured embroideries by Matt Smith, based on 18th-century patterns, in which the faces of the subjects have been left blank; and a small selection of photographer Zanele Muholi’s black-and-white portraits of trans, non-binary and lesbian South Africans from the series Faces and Phases. (A larger selection from the series has been given its own separate exhibition, which runs concurrently in the South Gallery.)

[image16]

Also on show are two works specially commissioned by the Charleston Trust. Paul Kindersley has interpreted Orlando as a bacchanalian film, which involves large quantities of smudged makeup, fancy dress and gratuitous feasting. Delaine Le Bas, an artist of Romany heritage, has been invited to respond to an episode in Orlando in which the protagonist marries a gypsy, fathers her children, and then disinherits their offspring. Le Bas has assembled a Tracy Emin-esque installation, complete with a messy writing desk, nude photos of the artist inside Charleston House and diaries left open to reveal personal musings.

[image2]

On the surface, it is clear enough why the contemporary artists have been selected. Yet, at times, the connections to Woolf are overstressed, to the detriment of both parties – particularly when contemporary works are put to use in framing Woolf in the identity politics of today. “Woolf was reclaiming literature as a female, feminist, queer being,” reads a wall text placed beneath one of Muholi’s portraits, attempting to bind artist to writer, and Muholi’s subject to Woolf’s white, aristocratic protagonist. The language used would have been entirely alien to Orlando’s author, given that the current meaning of queerness originated in the US in the late 1980s. And while Orlando may be a love letter, it is worth remembering that it is also a florid complaint about Sackville-West’s inability to inherit her family’s enormous country estate, owing to the system of primogeniture. Sexist? Certainly. But not something most people are in a position to empathise with. Woolf may have been an ardent advocate for women’s equality, an outlier for celebrating the loosening of gender roles, and a supremely talented writer, but intersectional icon she is not.

[image20]

Charleston’s curators face a problem that is increasingly familiar. How to run an exhibition programme with a mandate to make contemporary art relevant to a specific historical figure or group, without short-changing your exhibitors – or, indeed, the history you seek to promote? (Turner Contemporary has previously come a cropper in its overzealous and literal attempts to tie exhibitions to its namesake. To my horror, I once read a caption explaining that a sculpture made from piles of charcoal had been included because Turner liked to draw.) If Orlando at the Present Time connects past to present heavy-handedly, the curators may have already found the answer to their problem. In the South Gallery across the way, an entire room is given to a larger selection of photographs from Muholi’s Faces and Phases series. Free from the burden of directly mirroring Orlando, the work is able to operate on its own terms.

Muholi began the series in 2006, after South Africa legalised gay marriage. While the country has some of the world’s most liberal laws when it comes to trans, lesbian and gay rights, it remains notable for the ways in which this fails to impact on societal attitudes, meaning that violence is widespread. Muholi’s portraits are concerned with doing the blunt work of representation for those whose circumstances may otherwise go untold. Their subjects, photographed numerous times and shown in different “phases” of gender presentation, are invariably stoic.

Also on show in the Wolfson Galleries is Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant’s Famous Women Dinner Service, a set of 50 plates commissioned by popular cultural historian Kenneth Clark in 1932.

[image8]

On white ceramic, the faces of a jocular selection of women through time are painted as colourful, cartoon-esque illustrations – subjects include Cleopatra, Marie Antoinette and Miss UK 1933. Woolf and Bell also made it on to the plates, as did Duncan Grant (the only man in the collection).

[image13]

[image14]

Having painted themselves into the history, the stars of the show at Charleston will always be the Bloomsbury Group, and, of course, the house itself. Giving the contemporary art space to breathe will help more nuanced affinities – and productive differences – to arise. Like Muholi, any one of the artists included in Orlando at the Present Time would have been better served by having A Room of One’s Own.

• Orlando at the Present Time, Zanele Muholi: Faces and Phases and Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant’s Famous Women Dinner Service all run until 6 January 2019 (Wed to Sun) at Charleston, East Sussex.

-Kaye-Donachie.jpg)

-Paul-Kindersley.jpg)

-Matt-Smith.jpg)

-Estate-of-Vanessa-Bell-courtesy-of-Henrietta-Garnett.jpg)