Guggenheim Museum, New York

2 April – 27 September 2021

by TAUSIF NOOR

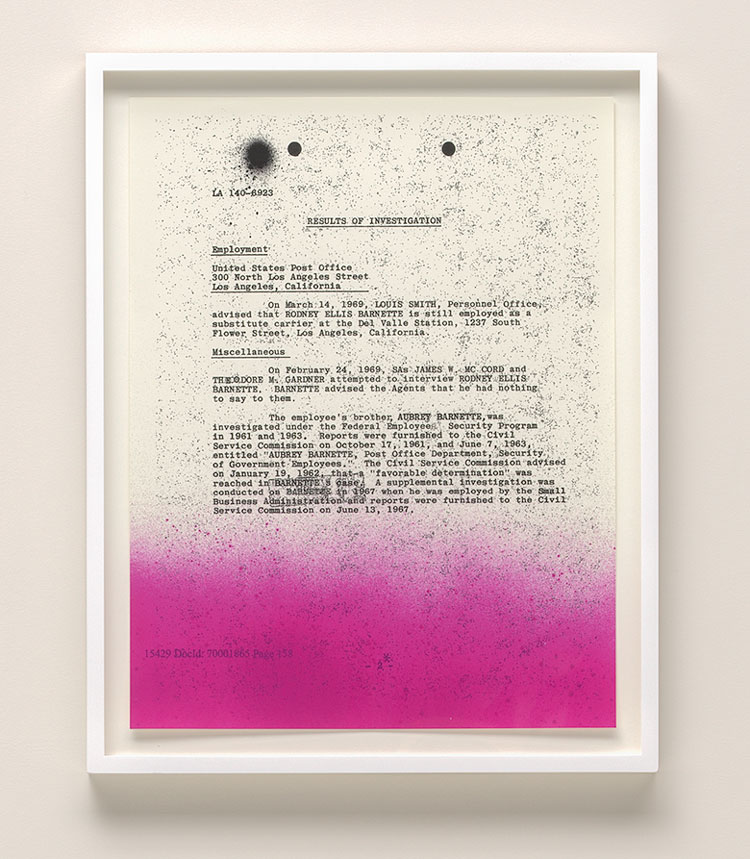

In 2013, the artist Sadie Barnette filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to obtain access to FBI records on her father, Rodney, a postal worker who founded the Compton chapter of the Black Panther Party and was consequently put under surveillance as part of the federal government’s counterintelligence programme. The Freedom of Information Act, passed in 1967 to assuage cold war anxieties regarding the federal government’s inclination to keep its inner workings secret from its citizens, requires federal agencies such as the FBI to partially or fully disclose unreleased government documents to anyone who makes a request. In recent decades, it has been amended to accommodate digital formats ushered in by the advent of the internet and has thus become an invaluable tool for journalists in particular to levy checks and balances against government authorities – an asset to a profession that has been described as writing “the first draft of history”.

[image1]

When Barnette’s request was finally completed in 2017, she received about 500 pages of material, five pages of which she marked with neon-pink spray paint and arranged within neat white frames in a serial format to comprise the 2017 work My Father’s FBI File; Government Employees Installation. The source material provides insight into Rodney Barnette’s personal and professional life, including his living arrangements and relationships with his family, as well as the extent of governmental intrusion into the private lives of individuals. But it is Sadie Barnette’s matter-of-fact presentation of US political bureaucracy, filing numbers and scans of manila envelopes included, that most evocatively illuminates how decades of racist violence and political suppression were administered through the most mundane of methods – paperwork.

[image6]

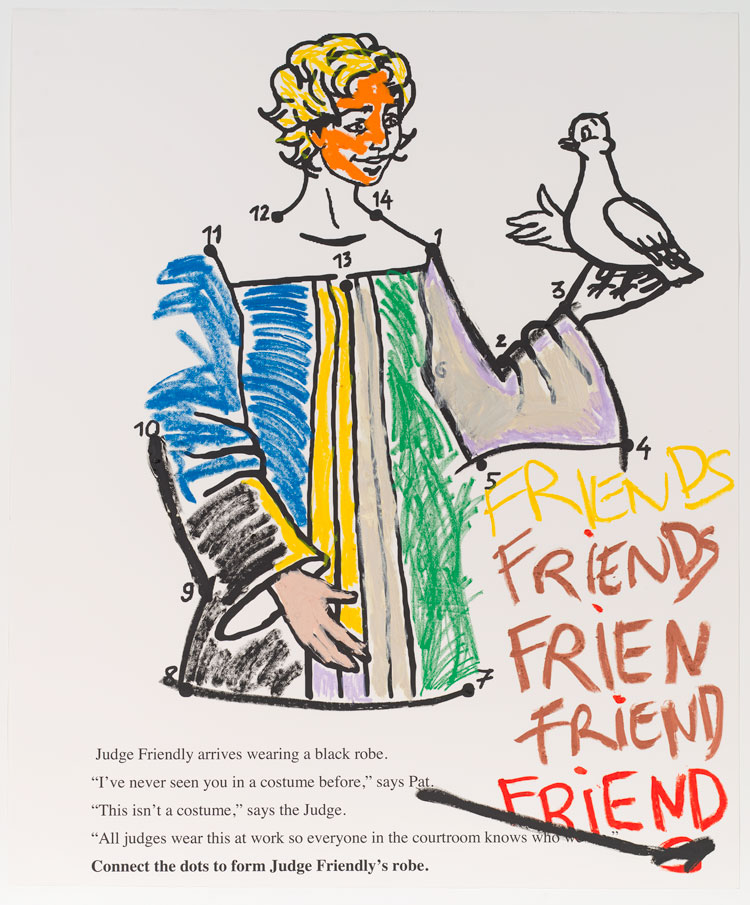

Indexing the tension between hidden information and the process of revelation, Barnette’s piece is both coda and the originating inspiration for Off the Record, an exhibition organised by associate curator Ashley James that comprises photographs, paintings and installation from the Guggenheim’s contemporary collection and places pressure on the function of “official” documents as neutral records of history. Surveying conceptual work made since 1990 by an intergenerational group of artists who use redaction, obfuscation and juxtaposition to address historical and sociological concerns, the exhibition addresses topics ranging from the taxonomic classification of enslaved people as “physiogamatic types”, as seen in the work of Carrie Mae Weems, to the sinister propaganda distributed by the contemporary prison institutions in America, as presented in Sable Elyse Smith’s large-scale Coloring Book pieces. What emerges from this expertly organised array is the recognition that the gap that so often separates truth from its purported documentation by “official” record is wilfully maintained by institutions – universities, prisons and governmental agencies among them – in order to maintain and advance the primacy of institutional authority.

[image4]

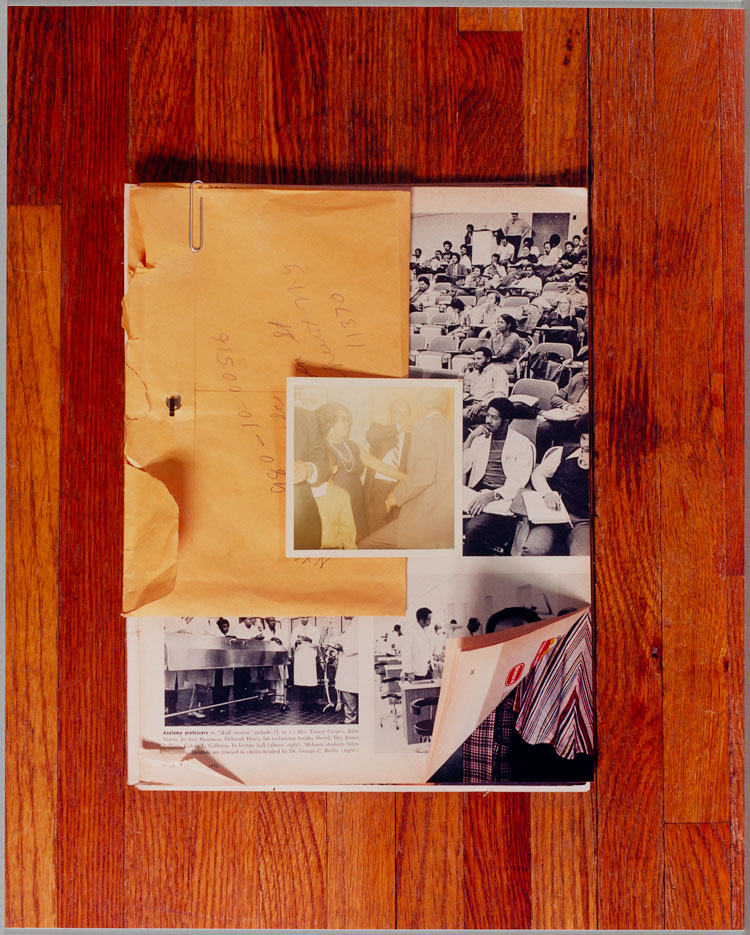

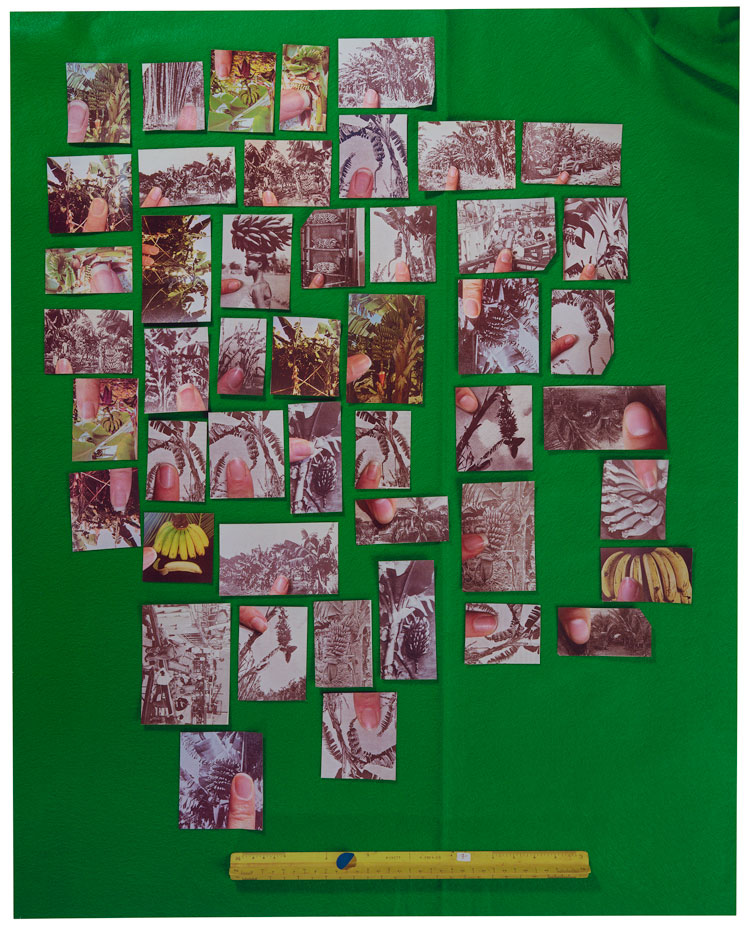

The most evocative works in Off the Record emphasise that subjective experiences and knowledge function as powerful tools for destabilising received information and mediating history. For the series Riffs on Real Time, 2006-09, Leslie Hewitt produced a series of photos by layering personal archival materials, including family photos and the envelopes and paper clips used to store them, atop popular black cultural magazines such as Ebony and Jet and photographing the resultant assemblages from above. Set against the mahogany backgrounds of hardwood flooring and carpeting, these photographic assemblages can be read as forming an architecture of black cultural life that is buttressed by personal and collective history, a sentiment that is echoed in Lorna Simpson’s Flipside (1991).

[image5]

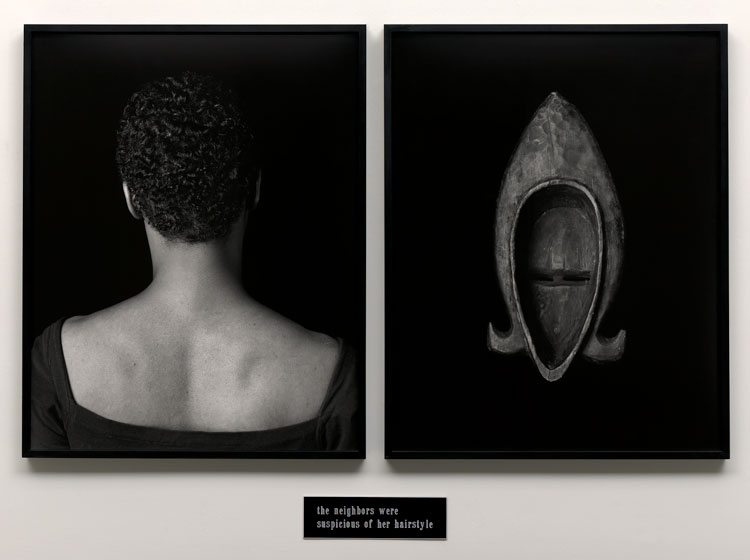

Using similar strategies of juxtaposition, Simpson positions an image of an unnamed black woman next to that of an African mask, both turned away from the viewer. Below this diptych, the artist has added the words “the neighbors were suspicious of her hairstyle”, synthesising, in a studied economy of form, the long history of surveillance and objectification to which black women have been subjected under the western colonial gaze.

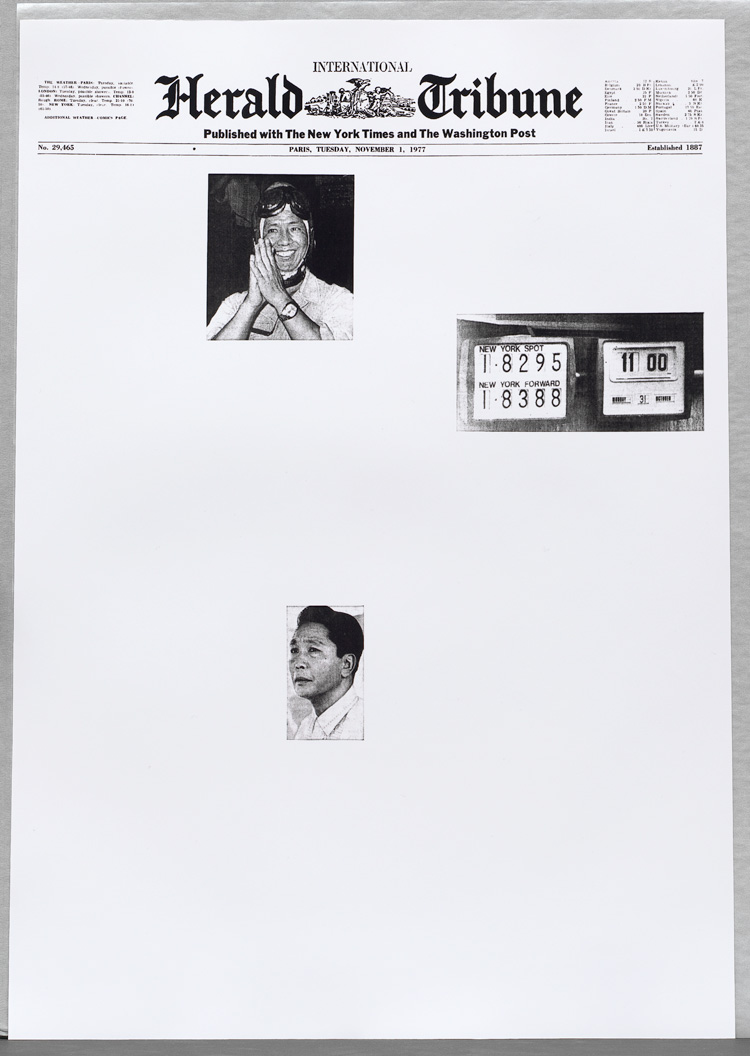

Simpson’s assemblage, much like that of each of the works mentioned here, underscores a salient aspiration of the artists in this exhibition to “correct” the record not simply through additive means, but rather by illuminating the tensions that structure the act of record-keeping – tensions between individual and collective histories, between ideological underpinning, and within the many gaps and erasures in the record itself. Several works in the exhibition, such as Lisa Oppenheim’s beguiling images made from the “killed” negatives of Walker Evans’s Depression-era photographs commissioned by the Farm Security Administration and Sarah Charlesworth’s redacted covers of the International Herald Tribune in 1977, astutely attend to such tensions between the record and that which eludes its hold.

[image2]

Their metacritical stance strengthens the exhibition, which in many ways is a timely rejoinder to the previous presidential administration’s peddling of fake news and the cottage industry of fact-checkers, professional and otherwise, that has sprouted as a consequence. Read against the grain of current affairs and considered alongside major exhibitions that focused on secrecy and official record in the last few years, such as the Met Breuer’s 2018 Everything is Connected: Art and Conspiracy, Off the Record builds on contemporary interest in the limits of fact and fiction by situating such concerns within the production and circulation of the official record across time.

[image7]

Subtly, and perhaps too subtly, Off the Record is undergirded by the crucial question of access: how access in its broadest sense mediates notions of “official” and “record”, and how artists forefront or de-emphasise their own methods of accessing records to lend either credence or an enigmatic air to their practices. Barnette’s use of FOIA to obtain her father’s records is duly noted in the exhibition didactics, as are Sara Cwynar’s consultations of Yale University library records, while other artists draw on materials in the public domain. Yet one wonders how Oppenheim came into the possession of Walker Evans’s negatives to make her own photographs, or how, after being purchased by the Guggenheim via the funds indicated on each of their respective wall labels, each of the works presented here enter into a new kind of record of institutional validation, approval, and canonisation. The museum, after all, is but one more repository of records with its own byzantine system of redactions, erasures and juxtapositions, and as this exhibition quietly suggests, it, too, is deserving of the same degree of scrutiny.