Drawing Room, London

10 September – 1 November 2020

by EMILY SPICER

In this age of science, ghosts and spirits are the stuff of entertainment, a cheap thrill found in horror films. But for many – and not that long ago – they were real entities, companions, even, that offered comfort and inspiration, as well as the occasional fright. Not Without My Ghosts, at Drawing Room in London, dips a toe into this nebulous world, revealing that the relationship between spiritualism and art is often a surprising one.

[image5]

William Blake (1757-1827) famously communed with the spirits of the deceased via shimmering visions on his walks around London. The wispy drawing displayed here depicts the ghost of Voltaire, drawn during one of Blake’s late-night sittings. The wall text emphasises that the artist and the philosopher shared common ground; both were non-conformists who advocated freedom of speech. But Blake was also critical of Voltaire’s Enlightenment rationality, believing that not everything can be known by science.

Next to Blake’s vision of Voltaire, hangs a tiny scrap of paper displaying doodles made by Victor Hugo (1802-85) while he was in exile on the island of Guernsey. When he was not penning great works of fiction, Hugo was a keen artist with a particularly gothic sensibility, who also participated in seances. Perhaps his murky ink and charcoal fragment with the words “dentelles et spectres” (laces and ghosts) scrawled across the bottom, was the product of a night of communing with the spirits.

[image6]

Nearby, hangs one of Georgiana Houghton’s remarkable drawings, a tangle of purple lines and white spirals. Houghton (1814-84) was an artist and an avid medium. She believed that her hand was guided by spirits, some of whom had been artists in life. But what is striking about her style is its modernity, its vivid colours and abstract forms. The work on display here, The Spiritual Crown of Annie Mary Howitt Watts (1867), could have been painted 100 years later, proving, if nothing else, that the belief in spiritualism freed artists from the conventions of the day. There is nothing polite or restrained about these paintings. Yet they are beautiful things out of time, the works of an unfettered mind.

Spiritualism also provided a way into art for those without artistic training. Included here is a large and mind-bogglingly intricate painting by coal miner-turned-artist, Augustin Lesage (1876-1954). At 35, Lesage reportedly heard a voice issuing from the darkness of the mine, telling him that he would become an artist. Guided, he believed, by his deceased sister, he went to work on large patterned paintings that, he said, depicted the architecture of cosmic planes. Made in 1924 and beautifully symmetrical, Composition Symbolique seems to represent a city of portals, a colourful metropolis for otherworldly beings.

[image3]

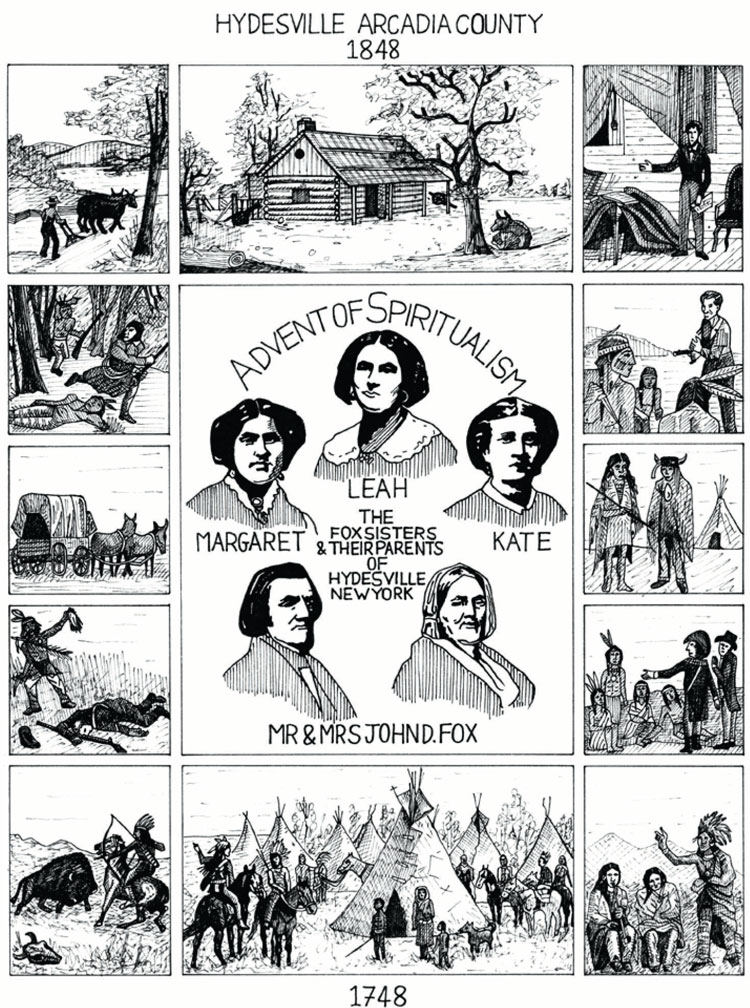

The second half of the exhibition shifts to more playful interpretations of spiritualism in contemporary art. Rather than drawing inspiration from otherworldly realms, Celia and Olivia Plender pay homage to the beginnings of spiritualism with a joint self-portrait titled Celia and Olivia Plender Raising the Fox Sisters (2018). In the late 1840s, Leah, Kate and Margaretta Fox claimed to hear a ghost in their home in New York. Their accounts caused a sensation and, for many years, they went on to enjoy successful careers as mediums, until Margaretta, revealed that the ghostly noises they had heard as children had been part of an elaborate hoax. By this point, however, spiritualism had taken on an international momentum.

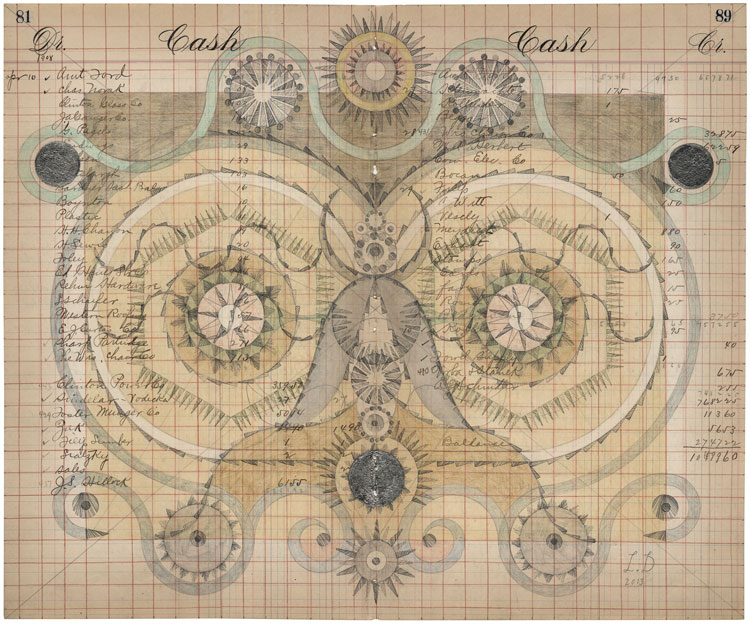

It is easy to scoff at those who believe they can communicate with spirits in our modern age, but the artist Susan Hiller (1940-2019) took an investigative approach to all that is otherworldly. Hiller trained as an anthropologist and, as she was finishing her PhD in 1965, came to the realisation that she could express her ideas about marginalised belief systems through art. Perhaps it was her background in anthropology that accounted for her open-minded approach to the occult. She experimented with automatic writing – a process used by mediums to speak to the deceased – and let her pen scribble fragmented missives, directed by her subconscious. Apparently, the experience did not convince her of the presence of spirits, but it did result in a strange stream of words and a sense that spiritualism, which was more often than not an expressive outlet at a time when artistic avenues were limited for women, was unfairly denigrated.

This is not an exhibition that will send shivers down your spine, despite Hugo’s seance drawings and Blake’s ghostly visions. In some ways, that is a shame because it is fun to be spooked, even when we know that phantoms exist only in our heads. But while this show will not leave you checking under your bed for ghosts and monsters before you go to sleep, it might stay with you for other reasons. After all, there are some moving elements here. Take for example Madge Gill’s beautiful abstract, consisting of a page of sumptuous, almost botanical, motifs. Gill (1882-1961) was a self-taught artist who first encountered her spirit guide, Myrninerest (my inner rest), after the death of her son during the 1918 influenza pandemic. Just as Lesage believed that the spirit of his infant sister guided him in his art, Gill’s mentor saw her through some tough times. So, perhaps those artists who commune with other worlds are instead drawing on an inner strength, reaching not an external realm, but some deeply personal part of themselves. And isn’t that the root of truly moving art?

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)