Museum of Contemporary Art, Grand Avenue, Los Angeles

29 August 2015 – 29 February 2016

by A WILL BROWN

On 29 August 2015, at the age of 32, Noah Davis, a Los Angeles-based painter and co-founder of the independent art space the Underground Museum, died from a rare form of cancer, at his home in Ojai, California. That same day, a re-presentation of his Underground Museum exhibition Imitation of Wealth opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Los Angeles. With Davis’s passing came a resounding sentiment of personal and professional loss from his peers, family and friends. Davis was known and respected for his profoundly frank and curious mind, as a painter, and as an artist with a burgeoning exhibition-based curatorial practice.

Davis, who was born in 1983 in Seattle, Washington, was an emerging yet notably established artist with a deep and rare commitment to painting. While he worked in the traditional medium, he was acutely aware of the social context of the art world and the implications of his work at large, and was simultaneously immersed in the conceptual art of his Los Angeles surroundings. At the Underground Museum, an alternative exhibition venue located in a storefront space in the Arlington Heights neighbourhood of LA, Davis and his co-founders – his brother, the film-maker and video artist Kahlil Joseph, and his wife Karon Davis, also an artist – brought great art to a traditionally working-class black and Latino neighbourhood.

Davis’s paintings are dreamy, at times pensive, figurative compositions with subject matter often derived from personal and found anonymous photographs or film stills. Much of his work depicted black figures in unremarkable situations, intimate yet universally relatable moments captured with a wistful and softly stylised approach punctuated by strong blocks of colour that defined a rich yet subtle vernacular. When asked about his choice to paint during a 2011 artist talk at the Corcoran Gallery, Washington DC, Davis said: “Painting does something to your soul that nothing else can. It is visceral and immediate.” After a long pause, he continued: “I work every day, I love painting.” For him, painting was deeply personal, so much so that he struggled when speaking about his own work, but could talk at length about the paintings of his contemporary and historic influences.

In 2011-12 he made a series of paintings titled Savage Wilds, after still images from daytime talkshow and reality television programmes. While the Savage Wilds series depicted scenes ripe for political and social critique, Davis painted these works with more of an environmental approach to presenting the quotidian aspects of everyday life. His sense of responsibility as an artist was to painting, and as a person it was to making engaging exhibitions with museum-quality art in an untraditional context – these two facets, while easily intertwined, remained, importantly, distinct.

A natural, yet curious and collaborative autodidact, Davis attended Cooper Union in New York City from 2001-4, but left for LA before he graduated when he felt his art-school education was no longer pushing him. Despite not formally finishing art school, Davis was fluent in the history of painting and spoke of his admiration for well-known and obscure artists alike, including Leon Golub, Christian Schad, Eugen Schönebeck and Duane Hanson. Following his move to LA, Davis’s work was presented in solo and group exhibitions including 30 Americans at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington DC, The Forgotten Works at Roberts & Tilton, Culver City, California, Stranger Than Fiction at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, and Face Forward at LeRoy Neiman Gallery, Columbia University, New York.

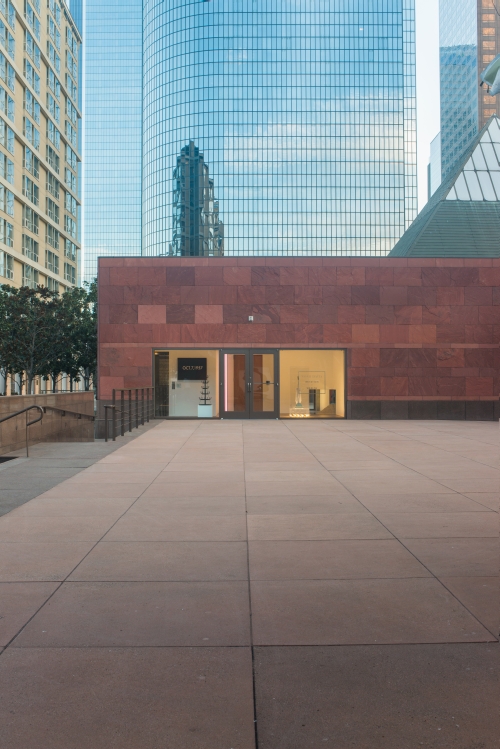

In what is Davis’s final completed project before his death, MOCA is hosting Noah Davis: Imitation of Wealth at its Grand Avenue location, as part of an ongoing programme called Storefront. Each year, the programme gives over MOCA’s Marcia Simon Weisman Works on Paper Study Center to two artist-run organisations to plan and execute an exhibition. The current iteration represents an exhibition that Davis first showed at the Underground Museum in 2013. For the original exhibition Davis remade, in near perfect facsimile, iconic artworks by famous artists, including a Jeff Koons Hoover sculpture, an On Kawara Date Painting and a Marcel Duchamp Readymade Bottle Rack.

The original exhibition posed interesting and provocative questions about authenticity, wealth, race and class. Davis made clear that he wanted to bring notably important museum-quality artworks to an area where they are uncommon, or perhaps never seen at all. While his intentions were clear, and seemingly quite true, the meta-analytic possibilities and interpretations of the original exhibition may be what endures from the project. A readymade fake Readymade presented in a storefront gallery in a working-class Los Angeles neighbourhood, available to all, as a precious idea and object, cast as an instigator of new thought processes, and also juxtaposed with other remade readymade-style art objects and installations – what’s realer than real here, and what is just a really good idea?

However, the central focus of the re-presentation of the exhibition at MOCA is the exhibition itself, and the gesture, as a medium and method of conveying and collecting information. At MOCA, the Storefront space is just that, except the doors leading into it from the outside are locked, and the works are visible only through the large glass windows. Further, the space isn’t a truly clean white cube and is ruptured by functional architectural elements, an elevator door, a locked double door, windows, and a door leading into the back of the museum. This confusion though, between what is and isn’t part of the exhibition – a shiny steel elevator door next to the fake Duchamp bottle rack Readymade – lends the space and the project an unexpected dynamic that asks one to consider where museums end and where they begin, and further where and how they make meaning from objects at all.

The loss of the initial context – the Underground Museum – is partly responsible for the deadening of the conceptual rigour of Davis’ project, yet in the wake of the artist’s death, the MOCA presentation becomes a memory-laden time-capsule, a tomb of ideas, at best an understated monument to a conceptual promise unfulfilled. One wonders is this an exhibition or an artwork, or is this an exhibition cast as an artwork – an object framed and untouchable, given conceptual and spatial meaning by its placement and context? While the project was made in good faith and with the artist’s engagement as part of what will be an ongoing series of shared exhibitions between the two institutions – MOCA and the Underground Museum – that ongoing collaboration itself might be the most interesting part of the project.

Noah Davis: Imitation of Wealth at MOCA falls short of the original concept, but it does raise important questions about how and why museums represent and work with artist-run independent exhibition spaces. The project is also resonant with the new hanging of the permanent collection in the MOCA galleries, for which chief curator Helen Molesworth has staged many of MOCA’s great works from the 20th and 21st centuries in a remarkably balanced and intuitively coherent manner. One work in the new collections exhibition, a large wall filled with Allan McCollum’s cast Plaster Surrogates, created a nice dialogue with Davis’s exhibition in the storefront space overhead, as both embody many artists’ keen and continuing interest in interrogating ideas of value, copying, repetition and style.

In the end, though, Davis will be remembered for his intellect and his passion for art and ideas. In 2009, at his solo exhibition at the Tilton Gallery, New York City, Davis was asked by Shelley Wade: “What motivated you to be a painter?” to which Davis earnestly replied: “I just couldn’t do anything else?” How many artists really mean that?