Sion and Moore, London

18 May – 7 June 2018

by MK PALOMAR

For Sion and Moore’s launch show, Nigel Shafran: Work Books 1984-2018, the space is filled with waist-high, shallow aluminium troughs, supported by elegant wooden trestles tied with red rope flecked in yellow. “The devil is in the detail,” Shafran told me, as I pointed to the rope. Then he wondered whether the saying would be better in this instance if it said: “God was in the detail.” Shafran explained: “Michael Marriott designed the show … it was my idea to show these books from 1984 to the present day, but Michael helped how we did the installation and how it’s shown.”

[image2]

This intriguing arrangement changes the way we look at the works. Most often when you see books displayed in a gallery space they are either in vitrines, leaving the viewer to dodge their own reflection in order to see the display more clearly, or laid out in unruly scatterings across large tables. There is something almost agricultural in this display – the troughs echo a working environment not industrial factory or technical office, but more of a cultivating space. As Cristina De Rossi, an anthropologist at Barnet and Southgate College in London, explains, the word “culture” derives from a French term, which itself derives from the Latin word colere, meaning to tend to the earth and grow, or cultivation and nurture. “It shares its etymology with a number of other words related to actively fostering growth.”1

[image3]

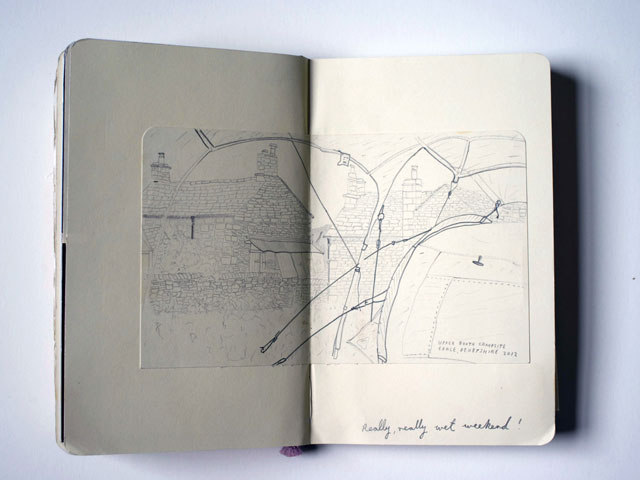

Here in Sion and Moore’s space, furnished with Marriott’s finely crafted floating troughs, Shafran’s Work Books, busy with notes and images, proposing, gifting, tantalising, suggesting, are indeed fertile ground. Rich with ideas, these pages trigger the viewer to wonder about the possible hidden stories on the pages we cannot see, to muse on the germination of the photographic works these pages led Shafran to make, and to seek to make our own connections to the multiple fragments offered to us from his everyday.

[image4]

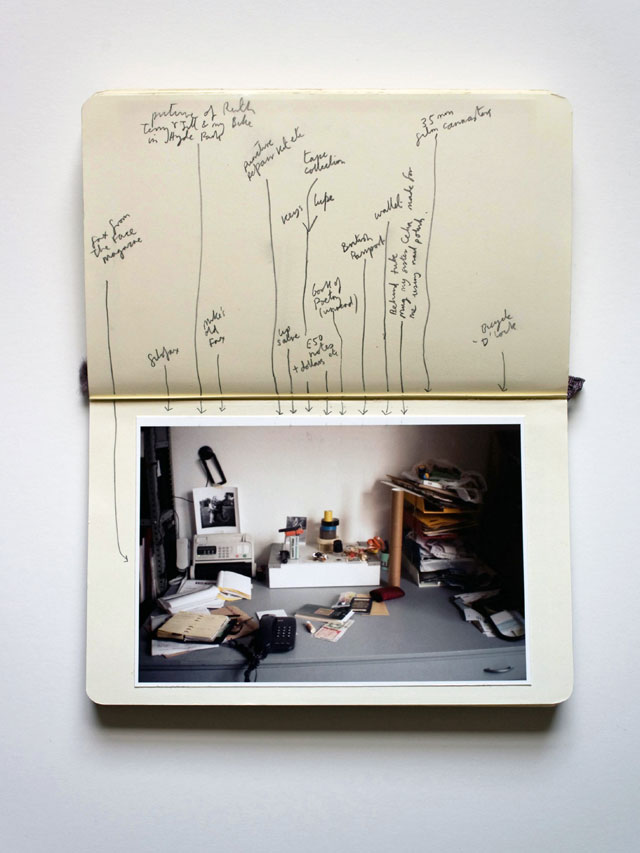

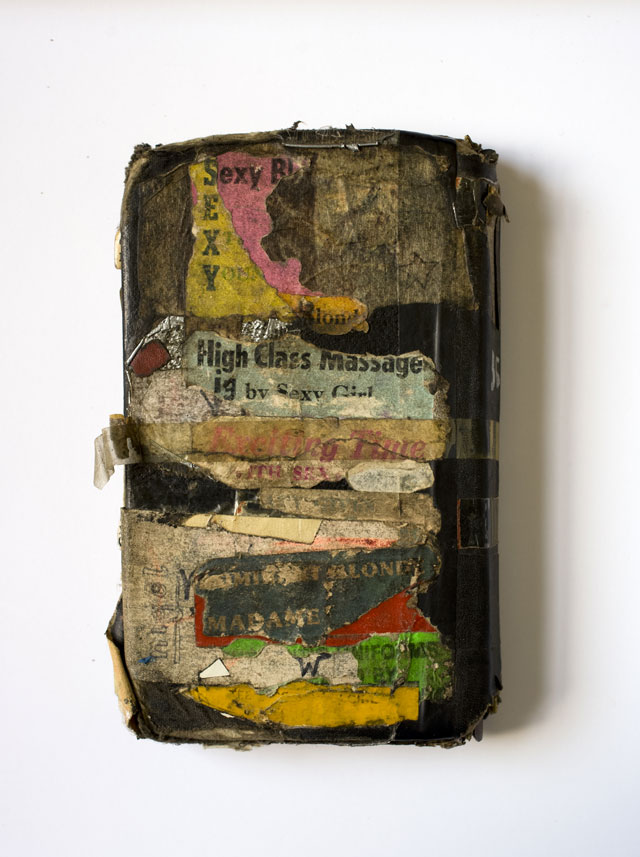

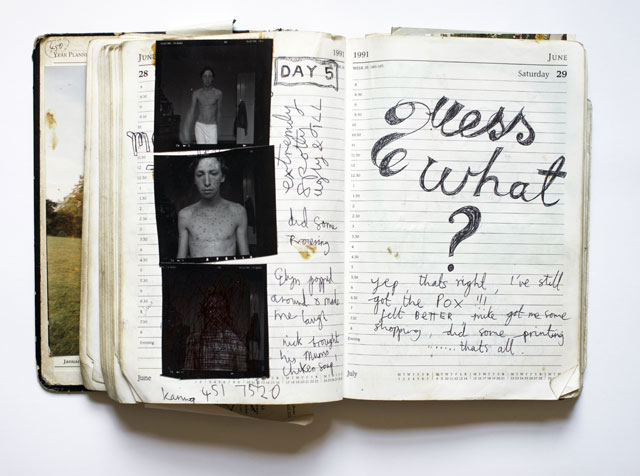

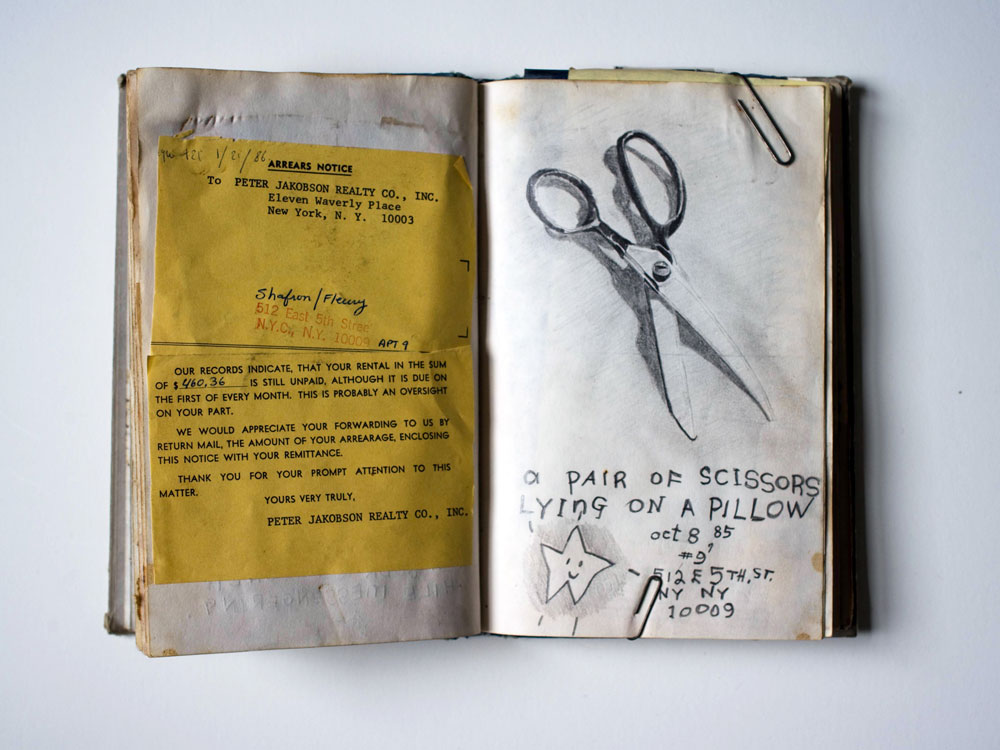

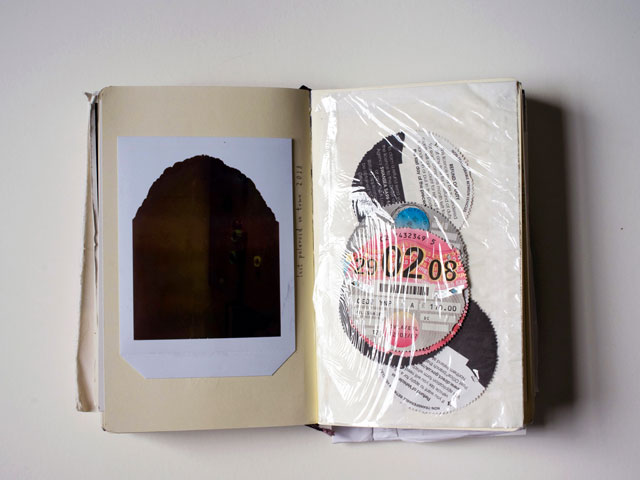

Shafran’s Work Books are various in shape and size; some have what in college circles is sometimes know as the cabbage effect – when the pages are so full of ephemera that the book won’t lie flat. Pointing to one double-page spread, Shafran, who began his career as a fashion photographer in New York in the 1980s, tells me: “One of my favourite photographers, André Kertész, died in 1985, the first day I looked at the New York Times.” On one side of the page, the headline and article is the snippet on Kertész. On the opposite page is a blue-toned colour Polaroid of a woman bearing a striking resemblance to Georgia O’Keeffe. This image is titled Lady in Central Park. “It’s an early picture [I took] when I was a kid.” These books, which cover 34 years of thinking and collecting, not only document Shafran’s ideas, stories and creative selection process, but they also reference the changes of creative materials, from newspaper image to Polaroid to digital print. This collection of images shown in this way is, Shafran says, his “version of Instagram”.

[image5]

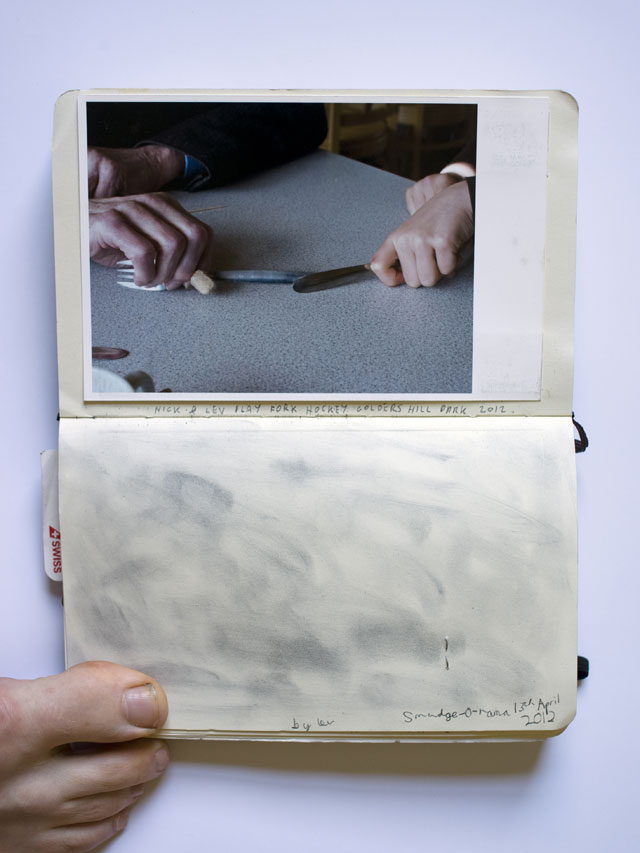

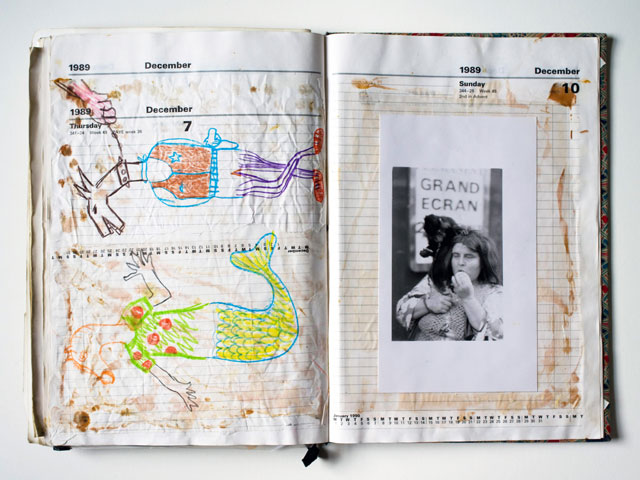

One book shows drawings of fantastical creatures, part-mermaid, part-horse, and opposite the coloured crayon drawings is pasted a black-and-white photograph of a girl with a monkey on her head. “That’s an early photograph from 1989 … it was the first picture I thought was really quite interesting with the writing and the image. It was significant at the time and I’ve never shown it and it’s nice to have these used books showing stuff.”

There are 41 books on display – one titled Ruth’s Book, and, further along, Ruth appears again wearing a mannequin’s wig. Shafran gives us tiny glimpses of his life, almost like numbers for a joined-up drawing, tempting us to fill in the gaps. There are a couple of drawings of pyramids and beside them is written 1 December 2007, view from the plane Alexandria and a building. Shafran suddenly bursts out enthusiastically: “Oh, my god, it’s such a fantastic place … it’s fantastic, I loved it so much … I went there to photograph the Biblioteca – it’s like a modern UFO in a way.”

[image6]

Another book is open at a double-page spread of drawings of mobile phones, some in coloured crayon and gold pencil, some chunky graphite sketches. “These are my son’s – it’s his mobile phones.” Shafran continued: “I’ve got a collection of newspaper pictures of footballers that look painterly.” The name Caravaggio is written alongside a newspaper photograph of a tight group of footballers. And it’s true, the stances, the grouping, the gesturing of the figures, the exaggerated facial expressions, these are the moments of an event held in time, as often portrayed in Renaissance paintings.

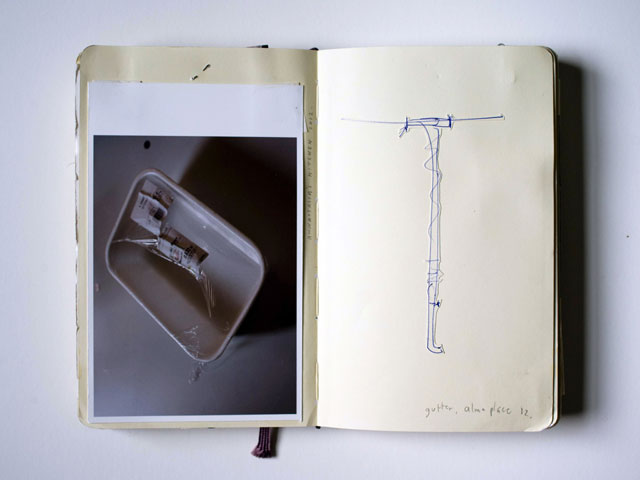

Shafran has made a lot of collections, of many different kinds. We see a series of whited-out shop windows – small square sections of whitewashed windows, each differently recording the motion of the hand-held rag that smeared a trace to block the onlookers’ view – and then photographs of people on the same place on an escalator. Perhaps, then, these illustrative notes, these selections of the everyday, are a type of pattern recognition, a search for a system to return to, a structure to fit a process into, so that it may be grounded firmly. Or perhaps it was just something that Shafran hit upon and was interested in for a day or two and sometimes longer. Next, there is a collection of printed forms, a series of number all signed and dated. Shafran explained: “I collect a lot of toilet notices. I’ve got one from the National Gallery.” Another book shows a photograph taken in 2014 at a motorway service station in France, with three almost identical young men, in and around a car, one holding a baby. Whose baby? Did they know? Where were they going? Why are there no women in the picture? It is not only that Shafran’s images and notes pose more questions than they answer, but also that they give you the beginnings of stories to dream about and imagine further, which is surely one of the most generous gifts of a good storyteller – to give you enough to set you off on your own imaginings.

[image7]

Each book is open at a double-page spread and secured to the surface – there is no option to flick through the pages (and although three flat screens displayed on one wall show a hand turning the pages of different books, the pace is quick, no lingering here). I am tantalised by Shafran’s choice of pages, and by not being able to see any further.

I asked him how he came to select the pages on display. “I like it, instinctively I like it – it’s a picture. I don’t know, there are some things I like and I think it helps define our choices in the everyday … what you choose is your edit – what you decide to show. You know, a monkey could be a brilliant photographer but it just doesn’t know how to edit. It’s an edit of work, I guess, and searching for what fits together functionally, aesthetically and emotionally … how it works ...”

[image8]

In the last notebook I look at, there is an image of a beautiful tall tree – it reminded me of the Dutch painter Meindert Hobbema’s picture of an avenue of poplars, The Avenue at Middelharnis, and that, in turn, reminded me of a contemporary image of poplars in Iraq. Struggling to remember the title, I asked Shafran if he knew the image. “Isn’t it Simon Norfolk,” he offered. (Norfolk’s image is The North Gate of Baghdad, 2003). I had mused on Shafran’s image, got lost searching for my familiar connection and been set right again by Shafran, lucid with imagery and sure on his mass of visual information. “You never want to have a house near a poplar tree,” he warned me. “The roots are longer than the tree itself.” Being among Shafran’s Work Books sets you off on all manner of connecting imagining and dreaming.

Reference

1. Cristina De Rossi quoted in: What is Culture? | Definition of Culture by Kim Ann Zimmerman in Live Science, 12 July 2017. (Accessed 18 May 2018)