National Gallery, London

22 February – 31 May 2020

(Due to the coronavirus, the National Gallery is temporarily closed until further notice)

by JOE LLOYD

There are many painters with a gift for catching the minutiae of life but, for a short period in the 1650s, there was perhaps none who did so with as much generosity as the Dutch artist Nicolaes Maes (1634-93). Young Girl Threading a Needle, a minute masterpiece of 1657, has its protagonist entirely absorbed in her task. Maes deftly embodies the intent in her face. The surrounding room, itself well-detailed, becomes of peripheral interest to the girl and the graceful act itself. We become witness to the joy of small things.

[image3]

Maes is the subject of a meticulously researched survey at London’s National Gallery, organised in collaboration with the Mauritshuis, which is now unfortunately shuttered. In the age of self-isolation and social distancing, Maes’s fixation on the comings and goings of bourgeois households has suddenly become newly apposite. He did not arrive at what is now known as “genre” painting – a light-hearted style starring nameless, not-quite-archetypes in quotidian settings – straight out of the gate. He spent five years as a pupil of Rembrandt, and early on tried his hand at the sort of grand histories at which his tutor excelled. Christ Blessing the Children (1652-53), a lively, warm-toned piece demonstrates Maes’s undoubted skill in that area. It was once believed to be a Rembrandt.

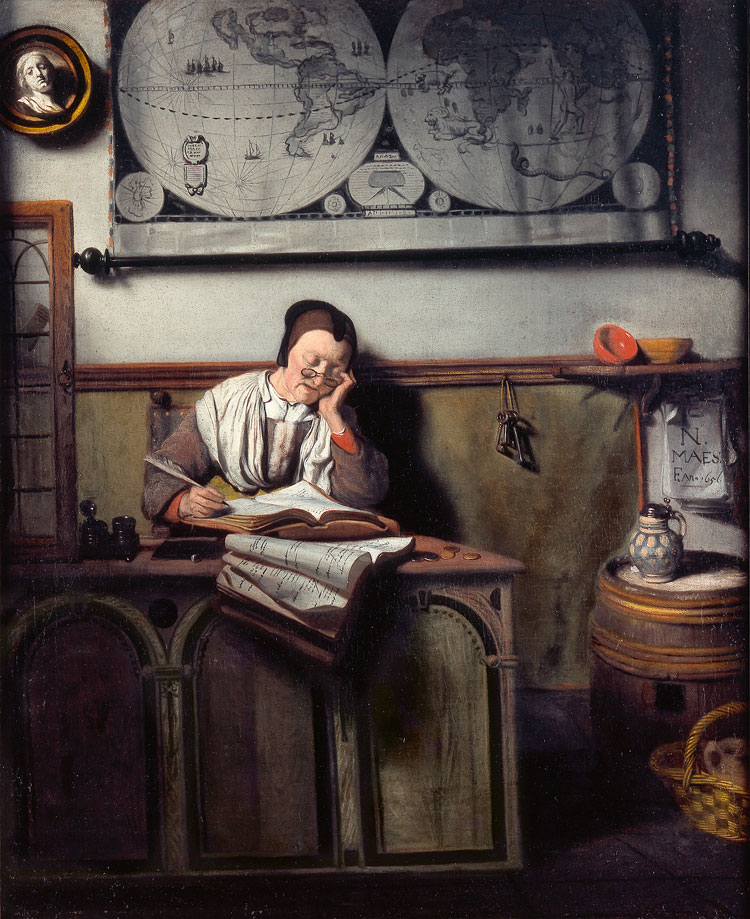

By 1654, though, Maes had turned from biblical subjects to those of the everyday. Between 1654 and 1658, while resident in his native Dordrecht, Maes produced several dozen paintings unobtrusively depicting moments and interactions that usually pass unobserved. A significant proportion feature women. In one, a girl leans out of her window to take the air, lost in thought; in another, a mother takes a break from reading to check on her baby, sleeping in a wicker cradle. Maes’s subjects are constantly dozing off: while reading the Bible, while doing their accounts, after indulging in wine and tobacco. If Maes has the lightest of presences, his characters push themselves centre stage. The somnolent drunkard is set on by a pickpocket, who cheekily turns to us as she rifles through his clothing.

[image4]

Maes quickly developed a talent for narrative clarity, and for ever-more-complex arrangements of interior spaces. In The Idle Servant (1655), the lady of a house enters her kitchen to find her maid asleep on the floor before a clutter of uncleaned pots (behind, a cat steals a chicken). Gesturing towards her sleeping servant, Maes’s lady looks towards us with wry amusement. In the background, up a small staircase, we see the gathering the mistress has left, including her empty chair. Perhaps she has come to fetch more wine. Though Maes was not the first Dutch artist to depict a multi-roomed home, the narrative linking of the two spaces had seldom been so explicit. The pots and pans add elements of the still life, folding in another genre.

The sequence of six paintings entitled The Eavesdropper, three of which hang at the National Gallery, represent the apex of Maes’s genre experiments. A figure smiles conspiratorially out of the picture as if addressing the beholder, index finger to lips in an almost-audible shush. Behind, in a room on another level of the house, a furtive amorous encounter is taking place. Each of these works has its peculiarities. In one 1655 version, the kissing couple share their undercroft with an old man, who shines a torch and stares directly at us. We have been discovered. Another of the same year has a maidservant overhearing her raging mistress in the chamber above. A gleaming curtain alerts us to the theatricality of the set-up.

[image10]

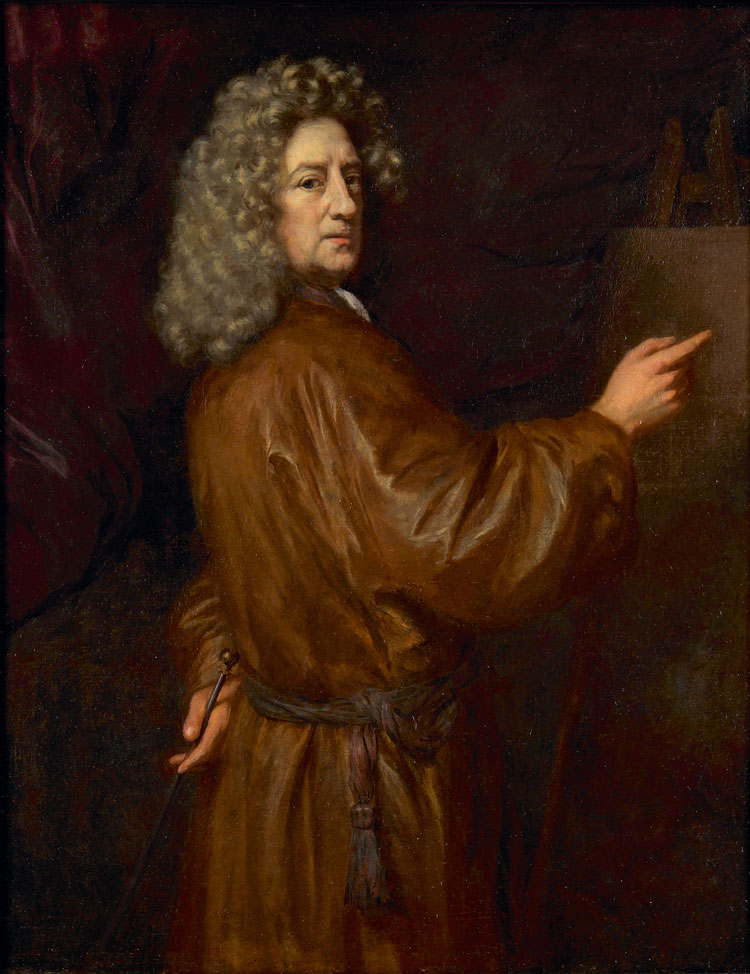

These brilliant tableaux would inspire Maes’s slightly older contemporaries Pieter de Hooch and Johannes Vermeer, but Maes himself did not take his innovations further. In a fascinating about-turn, he reinvented himself completely. From 1656 onwards, he shifted wholesale to portraiture, first in the sober mode of the Dutch Golden Age and then increasingly a breezy, lavish style influenced by Flemish baroque with open-air backgrounds. He became enormously successful: his sole self-portrait, from the first half of the 1680s, sees him clad in a luxurious Japanese gown. No one, wrote his first biographer Arnold Houbraken in 1719 , had been “more felicitous … in capturing the likenesses of human beings”.

Houbraken’s capsule life ends with a tale of Maes mollifying an irate subject by repainting over her blemishes, and it would be fair to say Maes had a tendency to flatter. At times, he turned earthly models into symbolic ones, as with a sumptuous pair of paintings showing two children surrounded by allegorical creatures. But even when he dialled back a little – as with his quartet depicting four young members of the aristocratic Van Alphen family – his subjects acquire such a burnished beauty that they might as well be deities.

[image8]

For his individual sitters, Maes developed a series of stock poses, which allowed him to become extraordinarily prolific (he produced about 900 portraits in all). But his early talent for variation has some descendant in the Six Deans of the Amsterdam Guild of Surgeons (1679-80), his only known group portrait. Each man holds a different pose, while all staring out of the canvas as one, reinforcing their strength as a committee.

Art historians have often found it difficult to reconcile the two sides of Maes, to the extent that some in the 19th century theorised two different, roughly contemporaneous artists with the same name. In the immediate decades after his death, accounts such as Houbraken’s celebrated Maes as a portraitist while ignoring his “lower” genre work; later, with the rise of academic art history and the revival of interest in genre, he was acknowledged as a master of genre who sadly stooped to society portraiture. And while Dutch Master of the Golden Age foregrounds that innovative half-decade as Maes’s greatest legacy, it also signals that his extended second act demands further consideration.

![Nicolaes Maes, The Eavesdropper, c1656. Oil on canvas, 57.5 × 66 cm. The Wellington Collection, Apsley House [English Heritage]. © Historic England Photo Library.](/images/articles/m/044-maes-nicolaes-2020/07.jpg)